Senator Michael Bennett

Att: John Whitney

835 East 2nd Ave, Suite 206

Durango, CO 81301

Congressman Jared Polis

Att: Nissa Ericson

PO Box 1453

Frisco, CO 80443

Re: Continental Divide Recreation, Wilderness and Camp Hale Act

Dear Senator Bennett and Congressman Polis;

Please accept this correspondence as the comments of the above-referenced (Colorado Snowmobile Association, COHVCO, Trails Preservation Alliance) Organizations vigorously opposing the Continental Divide Recreation, Wilderness and Camp Hale Act hereinafter referred to as “the Proposal”. After a detailed review of the proposal, the Organizations have concluded that every area expanded or created in the Proposal would result in significant lost recreational opportunities for the overwhelming portion of visitors to the Proposal area, both currently and in the future. While there are significant lost opportunities there is also no additional protections for multiple use routes that might remain outside the Wilderness areas and no new areas are designated for OHV recreation. Additionally, frustrating these efforts is the fact that previous commitments made in previous Wilderness legislation in Congressman Polis office remain unfulfilled. The Organizations also still fail to understand the management concerns or perceived threats that are driving the discussion around the need for additional protection of these areas.

The Organizations have been visiting with your Office staff attempting to find some type of consensus position that we could support around these areas, but it appears those discussions have not been fruitful, as this version of the Proposal is the worst version of the Proposal the Organizations have seen in a long time. This is highly frustrating as the Organizations were actively involved in the development of the Hermosa Watershed Legislation where large and diverse community support was developed around the Hermosa Legislation and a wide range of protections for a diverse group of users was achieved. The Organizations had hoped the Hermosa legislation was a new model for developing land use legislation but that does not appear to be the case.

Before the Organizations address the specific impacts from the Proposal to recreational access in the Proposal area, the Organizations believe a review of four landscape level topics around Wilderness designations must be addressed as there is significant new research that weighs heavily against proposed designations and management restrictions. These four topics are:

- The imbalance of demand for Wilderness recreation with the opportunity provided in the planning area;

- The cost/benefit of providing recreational opportunities in the Proposal areas that have been heavily impacted by poor forest health;

- The inability to understand the management concerns that are driving the perceived need to designate these areas as Wilderness; and

- The significant negative economic impacts that result to local communities from Wilderness designations.

Prior to addressing our specific concerns around the Proposal, a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization advocating for the approximately 200,000 registered OSV and OHV vehicle users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA advocates for the 30,000 registered snowmobiles in the State of Colorado. CSA has become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling by working with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators. For purposes of these comments, TPA, CSA and COHVCO will be referred to as “the Organizations”.

1a. National trail opportunities and trail visitation are badly out of balance.

Prior to addressing the specific negative impact to all recreational opportunities that would result from the Proposal at a site-specific level, the Organizations believe it is important to establish a strong factual foundation for our concerns regarding recreational impacts from any Legislation that restricts multiple use access on public lands. The Organizations believe that any legislation must be based on best available science for management of the area to ensure that balance of goals and objectives and opportunities is achieved in the Legislation.

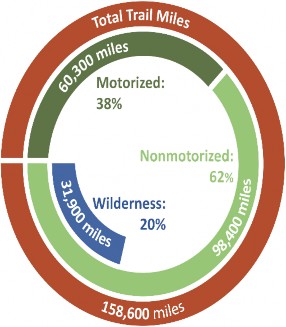

The first new piece of science and analysis that must be addressed in the Proposal is the imbalance in the opportunity to use trails in Wilderness when compared to the demand for these opportunities. The US Forest Service recently updated its National Trail mileage allocation, which is reflected in the chart below1:

Our concerns regarding the imbalance in miles of routes and possible impacts from any further expansion of routes in Wilderness are based on a comparison of the 20% of all trails are currently in Congressionally Wilderness, which is badly out of balance with the levels of visitation to these areas on the national level. In 2016, the US Forest Service research indicates that while 20% of all trail mileage is located in a Wilderness area, these routes are visited by only 4% of all USFS visitors.2 The Organizations simply do not believe that expanding this imbalance any further makes sense from a management perspective as 96% of a USFS are being forced to recreate on a smaller and smaller portion of forests (80%). The Organizations believe this simply makes little sense as land managers should be seeking to provide the best opportunity for the largest percentage of visitors as all visitors to public lands should be treated equally. Additionally, with this inability to disperse use, impacts at developed sites will continue as more of the public will be forced to recreate on smaller and smaller portions of public lands in the Proposal area.

1b. Local opportunities and visitation for trails is even more out of balance than nationally.

When USFS research is reviewed to determine recreational visitation to the land management offices involved in the Proposal area, it is determined that 3.4% of all visitors to the White River National Forest reported visiting a Congressionally Designated Wilderness area,3 despite more than 750,000 acres of the White River NF 2.3 million acres (32%) being currently designated as Wilderness areas.4 This low level of visitation to the White River National Forest is compounded by the fact that the WRNF has several Wilderness areas that are experiencing exceptionally high levels of visitation, such as the Maroon Bells. In order to balance this relationship, the Organizations submit there has to be large numbers of Wilderness areas designated on the WRNF that see almost no visitation throughout the year. As a result, the Organizations must question any factual basis that would assert recreational benefits from the Proposal, as currently there is almost twice the National average for Wilderness recreational opportunities but the usage of these opportunities is well below the National average.

The imbalance in winter recreational opportunities on the White River National Forest are even more of a concern, as the WRNF recently concluded that only 7% of the forest was identified as suitable and available for OSV travel. As a result of the small portion of the forest that is even available, any lost opportunity areas are VERY difficult for the snowmobile community to accept as they only have a small portion of the forest even available. While only 7% of the WRNF was available for OSV travel, significant portions of the WRNF are already unsuitable for OSV usage due to existing Wilderness designations on more than 34% of the WRNF.

Given the current imbalance of recreational demand with opportunities, both nationally and locally, the Organizations must question any assertion of a recreational benefit that could result from the Proposal, as currently these types of opportunities are horribly out of balance in the planning area when the supply of routes and trails is compared to the exceptionally low visitation overall. Rather that expanding opportunities for recreation on the forest, the Proposal would result in an even greater imbalance in usage than is currently on the WRNF.

1c. Forest Health, Recreation and Trails.

The Organizations are very concerned about the general scientific basis for the designation of the areas as Wilderness, as we are generally unsure of what management concerns are believed to be the basis for the special designations. Without a clear management need, any discussion around the designations is difficult at best and the Organizations must question why such management changes would be undertaken. Our research indicates that the areas proposed for some type of Wilderness or Special Management Area type authority are some of the hardest hit areas in the nation when forest health issues are addressed. That weighs heavily in our position against the Proposal. The expanded management restrictions that would result from the Proposal would prohibit the treatment of more than 7,000 acres of suitable timber that exist on slopes of less than 40%. These treatments could quickly mitigate fire risks in these areas and speed restoration of these acres to healthy and vibrant habitat for a wide range of species. These negative impacts should not be overlooked.

The Organizations are aware that both Senator Bennet and Congressman Polis have been very supportive of federal actions to address poor forest health conditions in Colorado, such as Senator Bennet championing of wide revisions to USFS contracting authority to address forest health issues in the 2012 Farm Bill and Congressman Polis vigorous support of efforts to move firefighting budgets out of the USFS budget and into FEMA management. The Organizations vigorously support and appreciate these efforts but must ask why this issue and concerns expressed in other legislation have not been addressed with the creation of the Proposal in order to minimize possible conflict between management guidance that is provided in these pieces of legislation.

The scale of the management challenge surrounding poor forest health is an issue where significant new research has been provided by land managers seeking to address this issue, and the conclusions of this research provide a compelling basis to avoid further management challenges on this issue. In 2015, the USFS recently completed research projecting the impacts of poor forest health on the national forests over the next 25 years and unfortunately, the federal resources in the state of Colorado did very poorly in this analysis as:

- the State of Colorado was identified as 5th in the country in terms of acres at risk due to poor forest health5;

- both Rocky Mountain National Park and Great Sand Dunes NP were both identified two of the hardest hit national parks in the Country6; and

- Colorado National Forests dominated the list of those forests hardest hit by poor forest health in the country as 5 of the top 7 hardest hit forests are immediately adjacent to the areas to be designated as Wilderness.7

It is unfortunate that Colorado does so well in these types of comparisons and analysis and the Organizations submit Colorado must be striving to resolve these issues rather than making these challenges more difficult. This type of research provides significant credible foundation for serious concern around a scientific basis for the Proposal. There appears to be significant conflicts.

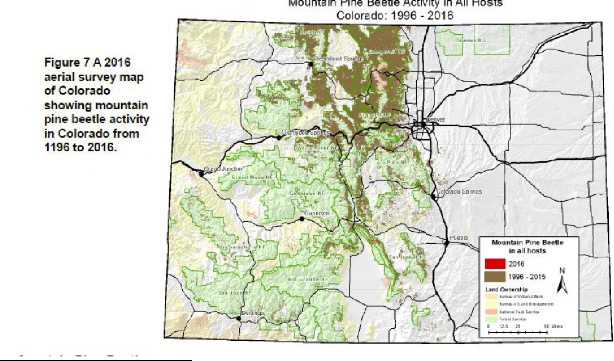

Newly released Colorado State Forest Service research provides the following graphical representation of the poor forest health in the vicinity of the proposed Wilderness and management areas as follows:

The Organizations believe that the poor forest health throughout the western United States is the single largest challenge facing public lands in our generation. While this outbreak has had horrible impacts to a wide range of activities on public lands, there is a small benefit to the current situation. At least we are aware what the single largest management challenge for our generation should be, which is how to we respond to this issue in a cost effective and timely manner. Given that the areas proposed to be managed as Wilderness or other special management designation are in the hardest hit areas in the state for tree mortality, the Organizations believe that the first question with any legislative action must be:

“How does this Legislation streamline land managers ability to respond to the poor forest health issues in the area?”

The Organizations vigorously assert that the Proposal is a major step in the wrong direction when addressing the ability of land managers to respond to the forest health concerns in these areas, as rather than streamlining the response to poor forest health issues, most areas are functionally precluded from management. Even where management is allowed the Proposal, the Proposal would result in another layer of NEPA analysis that would need to be completed prior to any management of the issue. Requiring yet another layer of NEPA from land managers who are seeking to address this issue makes little sense and the abnormally severe wildfires that result from poor forest health often render recreational access to burn areas unavailable for decades. Many of the routes impacted by the 2002 Hayman fire have only been recently reopened and many of the routes impacted by the Waldo Canyon Fire will remain closed for many years to come.

While the graphical representation of the poor forest health in the area of the Proposal is compelling the scope of these impacts is even more compelling when reviewed in terms of the sheer scale of the issue. The new research was specifically addressed in the 2016 Colorado State Forest Service’s annual forest health report. The highlights of the 2016 report addressing the sheer scale of impacts are as follows:

- 8% of ALL trees in Colorado are dead and the rate of mortality is increasing;9

- the total number of dead trees has increased 30% in the last 8 years;10

- Research has shown that in mid-elevation forests on Colorado’s Front Range,hillslope sediment production rates after recent, high-severity wildfire can be upto 200 times greater than for areas burned at moderate to low severity.11

- A 2011 study involved monthly monitoring of stream chemistry and sediment inSouth Platte River tributaries before and after fire and showed that basins thatburned at high severity on more than 45 percent of their area had streamscontaining four times the amount of suspended sediments as basins burned lessseverely. This effect also remained for at least five years post-fire.12

- High-severity wildfires responsible for negative outcomes are more common inunmanaged forests with heavy fuel loads than in forests that have experiencednaturally recurrent, low-intensity wildfires or prior forest treatments, such asthinning. It is far easier to keep water in a basin clean, from the source headwatersand through each usage by recipients downstream, than to try and restore waterquality once it is degraded.13

- During 2016’s Beaver Creek Fire, which burned 38,380 acres northwest ofWalden, foresters and firefighters were given a glimpse into likely futurechallenges facing wildfire suppression and forest management efforts. Theseinclude longer duration wildfires due to the amount and arrangement of heavyfuels. Observations from fire managers indicated that instead of small brancheson live trees, the larger, dead fuels in jackstraw stands were the primary driver offire spread…. “The hazards and fire behavior associated with this fuel type greatly reduce where firefighters can safely engage in suppression operations”14

The concerns raised in the Colorado State Forest Service research are by no means an anomaly. Wilderness and improperly managed Roadless areas were previously identified by the Forest Service as a significant factor contributing to and limiting the ability to manage the mountain pine beetle epidemic and poor overall forest health. The 2011 USFS research prepared at the request of then Senator Mark Udall’s office on this issue clearly concludes as follows:

“The factors that limited access to many areas for treatments to maintain forest stands—steep slopes, adjacency to inventoried roadless areas, prohibition of mechanical treatments in designated wilderness—are still applicable today.”15

The Udall Forest Health report continues on this issue as follows:

“•Limited accessibility of terrain (only 25% of the outbreak area was accessible due to steep slopes, lack of existing roads, and land use designations such as Wilderness that precluded treatments needed to reduce susceptibility to insects and disease).”16

This report is not discussed at length in these comments as previous comments have addressed this report. Since the release of this Forest Service report, additional Colorado Forest Service researchers have reached the same conclusions as the USFS Research Station did in the Udall Forest Health Report. The Colorado State Forest Service’s 2011 Forest Health report specifically identifies a major contributing factor to the spruce beetle outbreak as:

“Outbreaks typically occur several years after storms cause windthrow in spruce trees, which are susceptible to blowdown because of their shallow root system. Spruce beetles initially breed in the freshly windthrown trees, and subsequent generations attack and kill live, standing trees.”17

The lack of access to Wilderness areas to manage blow down areas is specifically identified as a major limitation in forest managers ability to address spruce beetle outbreak. These blow downs are directly identified as causing the spruce beetle outbreaks. The 2011 State Forest Service report specifically states:

“Many areas where spruce beetle outbreaks occur are remote, inaccessible or in designated wilderness areas. Therefore, in most cases, foresters can take little or no action to reduce losses caused by this aggressive bark beetle. However, individual trees can be protected on some landscapes.”18

The Organizations must note the 2011 State Forest Service report extensively discussed how EVERY major spruce beetle outbreak in the state of Colorado was associated with a major wind event in a Wilderness area, which could not be managed by foresters due to Wilderness designations. Given the clear conclusions of best available science, that Wilderness and other management restrictions are contributing to and limiting the ability of land managers to respond to the single largest management challenge that will be experienced in our generation, the Organizations must question why such a decision to further limit the authority of land managers to respond to this challenge would ever be made. Such a position would not be based on best available science.

1c. Wildlife habitat is degraded when management authority is restricted.

The Organizations are aware that generalized statements that the Proposal would improve wildlife habitat in the areas have been relied on previously, but the Organizations are not aware of any scientific basis for such a position. The Organizations are concerned about wildlife impacts due to the fact that many of our members are hunters and fisherman and directly benefit from healthy wildlife populations in the area. In addition to these consumptive wildlife concerns, many of the public are non-consumptive users of the large wildlife populations in the Proposal area and are provided a superior recreational experience from the large and healthy wildlife populations in the proposal area. The Organizations would also note that the delisting of any endangered or threatened species is often heavily reliant on a stable and healthy habitat for the species, and this is not provided by lands heavily impacted by poor forest health issues.

The Organizations wish to highlight several new pieces of research that address the need for active management of public lands and the need for a healthy forest for wildlife in the planning area. In 2015, Colorado Parks and Wildlife released its State Wildlife Action Plan(“SWAP”), which provided a brief summary of the challenges facing species of conservation concern and threatened and endangered species in the State of Colorado. The SWAP provides the following summary of the impacts to wildlife at the landscape level from poor forest health:

“Timber harvesting within lodgepole pine at the appropriate sites and scale is needed to maintain pure lodgepole pine stands for lodgepole obligate wildlife species. Continuing to increase stand heterogeneity to reduce large, continuous even-aged stands will help reduce risk of uncharacteristic wildfire and large-scale pine beetle outbreaks in the future.”19

In addition to the above quote addressing the landscape level concerns around poor forest health, more than a dozen species are identified where the degradation of habitat due to beetle kill was specifically identified as a significant threat to the species.20 These types of concerns and impacts are simply not resolved with additional restrictions on the ability of land managers to respond to the forest health challenges. Management must remain on target in addressing these challenges in order to respond to these unprecedented tasks in the most cost effective and timely manner possible.

In addition to the newly released SWAP, significant new research has been provided that clearly identifies the need to address poor forest health concerns for many other species. Forest fires have been identified as a major threat to habitat for the Endangered Colorado Cutthroat trout, both during the fire itself and from the condition of riparian area after a fire. The Forest Service species conservation report specifically states:

“Lack of connectivity to other populations renders them vulnerable in the short term to extirpation from natural disturbances such as fire, post-fire debris torrents, or floods….”21

The Conservation Report also noted the significant impact that woody matter has on the cutthroat trout habitat. The Conservation Report notes the impact of fire and insect infestation are both major impacts on woody matters stating:

“large wood (also known as coarse woody debris) plays a dominant role in many montane streams where greenback cutthroat trout persist. Deposition of large wood affects sediment scour and deposition, energy dissipation, and channel form (Montgomery et al. 2003), and creates pools, stores spawning gravels, affords overhead cover, and provides refuge during high flows…… Inputs of large wood are controlled by a variety of processes. Mass mortality of riparian stands from fire, insect damage, or wind is important sources.” 22

Fire is specifically identified as a disturbance that results in trout habitat being unsuitable for centuries, stating:

“In particular, disturbances that dramatically alter channels or riparian zones—debris torrents…and severe fires—will change the discharge-sediment transport regime, re-set forest succession and large wood dynamics, and redistribute suitable and unsuitable habitat in a basin, sometimes for decades or centuries…”23

This research notes the significant difference in impact to the cutthroat trout between conditions existing before the fire, during the fire and after the fires that are now occurring at unprecedented levels from the poor forest health existing in Colorado Forests. Given that the Colorado River Cutthroat Trout is one of dozens of fish species currently at risk due to the poor forest health on the WRNF, the Organizations submit best available science for species management weighs heavily against any expansion of Wilderness like management in the planning area.

2a. Existing recreational opportunities would be exceptionally impacted due to extensive restrictions on how basic maintenance of routes may be performed in new Wilderness areas.

Given the Proposal asserts to be driven by recreational interests, the Organizations believe this issue warrants a more complete review and analysis of impacts and benefits from the Legislation at a more localized level than the national update on recreation that was previously provided. This is another issue where the benefits of the Legislation are unclear. While the benefits are unclear, the significant negative impacts are immediately clear as any efforts to provide basic maintenance and management of existing opportunities in the areas where Wilderness management is expanded become far more difficult and available funding is significantly diminished.

It has been the Organizations experience that land managers are struggling badly with providing basic maintenance and safe access to existing recreational opportunities in the planning area even when mechanical means and tools are available to maintain these areas. This is simply due to the large number of falling trees, that block or otherwise routes in the area. As the Organizations have previously noted, Colorado is some of the hardest hit areas in the Country in terms of poor forest health and logic would conclude that recreational management challenges would also be the largest in Colorado in allowing recreational usage of beetle kill areas. The challenge is immense even with the most advanced mechanical maintenance equipment available and is realistically beyond cost effective management without mechanical maintenance equipment.

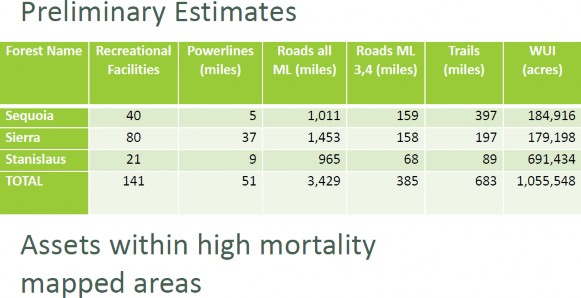

While the Organizations are aware that stating the challenges facing managers relating to recreational routes and facilities are immense has some level of value, there is also no replacement for hard numbers when assessing impacts. New research has been performed by the USFS in the State of California regarding the scope of the challenges facing land managers in maintaining recreation on three Southern California Forests heavily impacted by poor forest health. The USFS conclusions on these forests are as follows:

14

14

The Organizations believe any assertion that maintenance of existing recreational opportunities and resources encompassing more than 4,000 miles of roads and trails and 141 recreational facilities impacted by poor forest health without mechanical assistance would lack factual or rational basis. This type of challenge is even more difficult in Colorado as research previously identified finds that Colorado forests are significantly harder hit than the three forests in California that are the target of the above research. The Organizations are intimately aware that existing resources for maintenance of recreation facilities and routes in Colorado struggle badly to maintain opportunities with mechanical resources and management being allowed.

In this situation the Organizations must question why streamlining the land managers ability to provide safe high-quality recreational opportunities is not the priority of the Legislation. Instead of streamlining efforts, the Legislation provides a new and significant barrier to land managers responding to the issue. The Organizations are aware of the arguable authority for the Secretary to allow for mechanized treatment of forest health issues in the small portion of new Wilderness areas to be designated in §3c of the Proposal. The Organizations concerns on this issue are twofold:

- This type of analysis will require at least a round of environmental analysis to be performed and based on discussions around this type of management flexibility the Organizations can say with a high level of certainty that the environmental review process will be exceptionally difficult; and

- We are not aware of a single acre of Wilderness in Colorado that has been mitigated under similar provisions of the Wilderness Act.

As a result, the Organizations are opposed to the designations of areas under §3c and related provisions of the Proposal, despite the arguable authority to act, as the action would be both more expensive and has functioned as a complete barrier to action as this authority has never been used in Colorado.

Given the poor track record of mechanical treatment being allowed to protect recreational opportunities in Colorado Wilderness areas, the Organizations believe a review of the means of maintenance actually on the ground is warranted. While these comments are centering on the maintenance impacts from poor forest health, there are numerous other issues in providing basic maintenance such as rock removal, which in a Wilderness must be done by hand instead of mechanized equipment and simply transporting equipment to sites, which must be done by hikers or horseback instead of with trucks and trailers. This review is needed in order to fully understand the basis of our concerns around overall impacts to recreation and federal budgets that are required to fund maintenance with exceptionally expensive methods.

The most common manner of removing downed trees or hazard trees in a Wilderness based recreation area of Colorado is with a large crosscut saw operated by two people such as that pictured below: 25

Removing a tree such as that pictured above could be achieved in under an hour with mechanical means, but a similar removal could easily take all day without mechanical assistance. While a manual cross cut saw might be able to deal with isolated trees, such as these pictured above, the removal of hazard trees such as those photographed below are far more problematic.

The ability to safely removal a tree blocking a route in the manner pictured above is difficult even with mechanized assistance but becomes far more concerning when hand tools must be used simply due to the extended amount of time sawyers must be in proximity to the hanging tree and the fact that twice as many sawyers are needed for the removal of the tree. Even when dealing with an isolated tree crossing a trail, costs and risks associated with basic maintenance are greatly increased with the prohibition of mechanical upkeep.

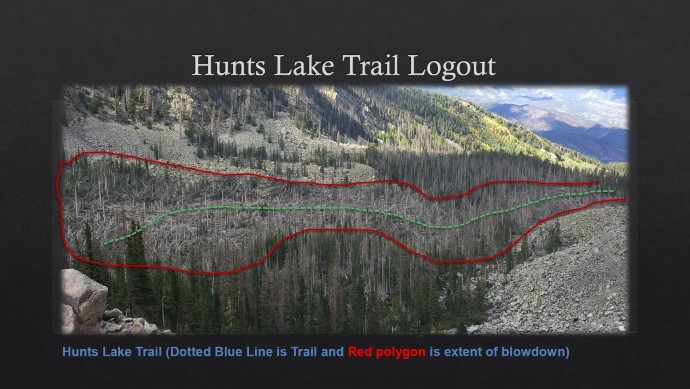

While there are concerns about the safety and cost of maintenance of Wilderness routes on a per tree level, concerns are expounded when maintenance is needed around larger wind events or larger scale tree fall issues such as those now commonly seen in beetle kill areas in the state. As a result of the serious limitations on how basic maintenance can be performed for major events like the blowdown that is currently blocking all public access to the Hunts Lake Trail on the Pike San Isabel photographed below are almost prohibitions on reopening routes:

Reopening of the Hunts Lake Trail would be a significant challenge with mechanized assistance but removing this number of downed trees without mechanical assistance would result in something that is a significant challenge to a project that might easily take months or years of effort if weather was uncooperative. Ignoring these types of on the ground impacts from expansion of management restrictions from the Proposal makes little sense and erodes any basis for claiming recreational benefits from the Proposal. There is simply limited funding available for recreation and that money must be applied in the most effective manner possible to protect existing recreational opportunities both inside and outside of Congressionally Designated Wilderness areas.

2b. Trail maintenance resources are greatly reduced in Wilderness areas.

As the Organizations have noted already, costs associated with basic maintenance of recreation facilities and opportunities are significantly increased with any Wilderness designations. Based on the Organizations experiences with the Colorado State Trails Programs grants, these costs are consistently identified as being something to a factor of 100x the cost of mechanized trail maintenance in grant applications to partner programs. The average mechanized maintenance crew can easily clear and maintain 100 to 200 miles of trail per year, while similar levels of funding and partner efforts utilizing non-mechanized means can only address 1-2 miles of trail per year. The cost benefit relationship is simply not comparable.

In addition to the exponentially increased costs of maintenance for recreational opportunities in Wilderness area, the amount of funding that is available for maintenance is greatly reduced. The USFS estimates the $4.3 million in funding available from the State of Colorado’s voluntary OHV registration program almost doubles the amount of funding available for summer recreational maintenance programs as follows:

26

26

This disparity of funding is even more problematic when the more than $1.5 million in additional maintenance funding that results from the Colorado Voluntary Snowmobile Registration Program is included in this equation.

The direct impacts of this funding are:

- EVERY Ranger District in the State of Colorado has access to a well-equipped trail maintenance crew funded by the voluntary OHV tax on a prioritized basis;

- Most ranger districts have a dedicated motorized trail crew for summer maintenance

- Most Ranger Districts also a winter maintenance crew from snowmobile registration funds.

While these teams have been hugely successful, their effectiveness is limited by available funding limits and when existing resources are used for maintenance in ways that are 100x less effective it impairs recreational experiences for all the public, not just those choosing Wilderness based recreation. The availability of these crews directly contrary to the national situation facing the forest service where most Ranger Districts have no maintenance crews at all. The Organizations believe that any legislation addressing recreational access and maintenance must be looking at how to making existing funding go further, rather than making existing funding less effective by a factor of almost 100, as is the result of Wilderness recreation.

Why are the economic resources available for maintenance of Wilderness recreation a concern for the Organizations, as our activities have been prohibited? While the voluntary OHV and snowmobile funds greatly expand the resources that are available to land managers for maintenance of facilities outside Wilderness areas, these resources are often leveraged with USFS budgets for maintenance of these areas. When the match to the funds provided through the voluntary OHV funds is asked to become less effective by a factor of as much as 100 for the benefit of less than 4% of all visitors to USFS land, the Organizations are immediately concerned that the match to the OHV program funds will be reduced. This reduction is concerning as no additional benefit is achieved with these funds but resources being leveraged for maintenance outside Wilderness are significantly reduced and the Organizations are intimately aware that these funds are often stretched very thin already. This is simply unacceptable to the Organizations.

3.Economics of Wilderness Recreation.

The Organizations are aware that many counties in the vicinity have moved away from the dark economic times that plagued them several years ago, as exemplified by Summit County Colorado identification as number 3 on the Wall Street Journal list of 21st Century Ghost Towns.27

Unfortunately many communities outside the direct influence of ski area-based revenue continue to struggle and overly rely on recreational opportunities to provide basic services to residents. Many of these communities might include Redcliffe, Leadville, Birdseye or Alma as examples. Given the importance of recreation to these communities and many of our members that live in these communities, the Organizations believe a brief update of the economic impacts to these communities that resulted from the Proposal is warranted. Significant new information identifies the strong negative relationship between Wilderness designations and local economic activity involving recreation.

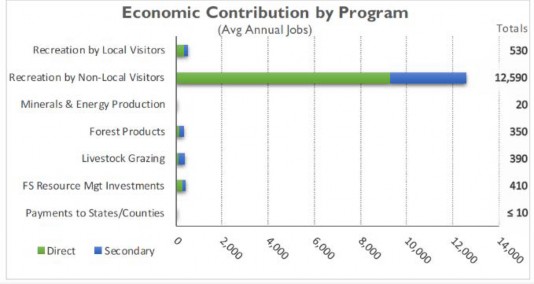

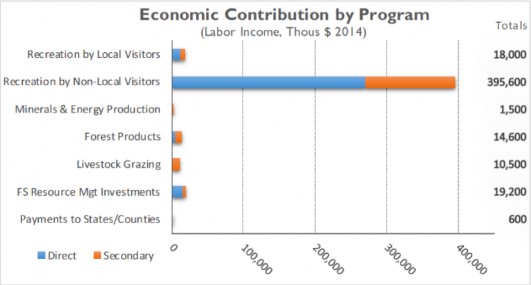

The first piece of new scientific research is the local economic information from USFS, as part of their “at a glance” summaries for the White River National Forest, which identifies the overwhelming importance that recreation plays in the success of local communities. The USFS summarizes their conclusions in the following graphs28:

It is difficult to understate the importance of the economic contribution of recreational activity to local communities, when the USFS estimates that the economic benefits of recreation outpace all other usages combined by a factor of more than 12.

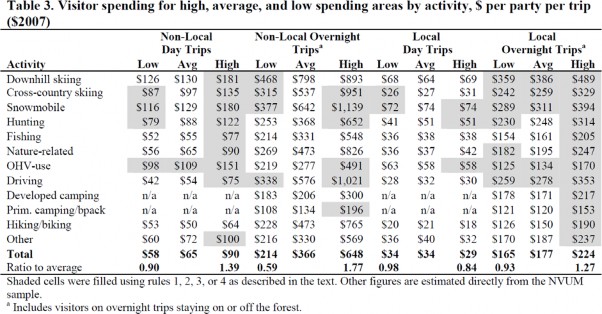

New research highlighting the economic importance of multiple use recreation to the recreational spending benefits flowing to local communities comes from research from the Department of Commerce. This analysis was prepared at the request of Department of Interior Secretary Sally Jewel in 2012, addressing the importance of recreational spending in the Gross Domestic Product.29 This research clearly identified the important role that motorized access plays in recreational spending, which is summarized in the following chart:

This research concludes that motorized recreation outpaces the economic contribution of boating and fishing at almost twice the rate and that motorized recreation almost outspends all other categories of recreation combined. Given that motorized usage plays major roles in both the hunting and fishing economic analysis, the three largest components of economic benefit from recreational activity would be prohibited in a Wilderness area. As a result of the overwhelming nature of these conclusions, the Organizations have to express serious concerns when the lion’s share of economic drivers are excluded from using any portion of public lands as clearly economic benefits are limited. The negative economic impact concerns regarding degrading multiple use access are immediately apparent.

The risk of negative economic impacts is also highlighted in newly released research from the US Forest Service, which estimates that recreation on National Forest Service Lands accounts for more than $13.6 billion in spending annually.30 Experts estimate that recreational spending related to Wilderness areas accounts for only 5% of that total spending or approximately $700,000 million nationally. 31 The limited economic driver of Wilderness based recreation is compounded by the fact that more than 20% of the trail network that is currently located on USFS lands is within Wilderness areas. Again, this type of underutilization of any recreational resource is concerning to the Organizations simply because of the allocation of the resources and funding.

The basis for the economic underutilization of Wilderness based recreational resources is easily identifiable when the USFS comparisons for economic activity of recreational users is compared. This research is summarized below:32

We will not be addressing this research at length as we have included this analysis in our previous comments on earlier versions of this legislation, other than to note the conclusions of this research are consistent with conclusions that high spending user groups, such as snowmobile and OHV users are consistently excluded from Wilderness areas, while low spending groups such as cross-country skiers and hiker are permitted in these areas. Given the fact that low spending profile users are often spending only 20% of higher spending profile groups, these conclusions are consistent with the conclusions of both the Department of Commerce and new USFS research.

While the imbalance in spending profiles is problematic, the fact that once Wilderness is designated the general public fails to use the limited recreational opportunities in these areas is even more concerning. Nationally, Congressionally designated Wilderness accounts for approximately 19% of USFS lands but results in only 3.4% of all visitor days.33 In the State of Colorado, there is approximately 22% of USFS lands managed as Wilderness34 but despite the expanded opportunity results in only 3.4% of visitor days on the White River National Forest.35 As we have noted in previous comments there are significant declines over time in the visitation to and demand for Wilderness based recreational experiences. Given the significant underutilization of Wilderness resources in the area of the Proposal, the Organizations must vigorously assert that any economic risk is significantly negative and must be addressed or at least recognized by the communities in the vicinity of the Proposal areas.

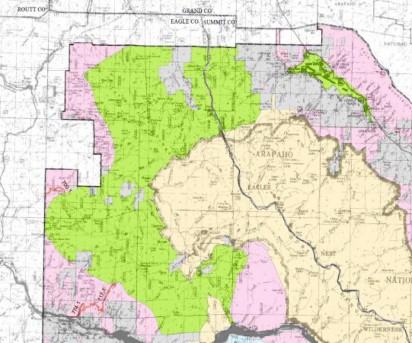

4.Most areas proposed to be Wilderness in the Legislation were found unsuitable fordesignation as Upper Tier Roadless areas in the 2012 Colorado Roadless Rule Process.

The Organizations were heavily involved in the development of the 2012 Colorado Roadless Rule, where both additional management flexibility was to be provided in Roadless areas and additional protection of less developed areas was explored. Extensive inventories of areas were provided as part of development of the Roadless Rule to ensure that best available information about the area was also relied on in the inventory process. As a result of this process, significant portions of the areas now proposed to be Wilderness or the subject of other exclusionary management standard were inventoried for possible inclusion in upper tier roadless designations under the 2012 Colorado Roadless Rule development. Every area proposed to be Wilderness was found suitable for management as upper tier only a few years ago.

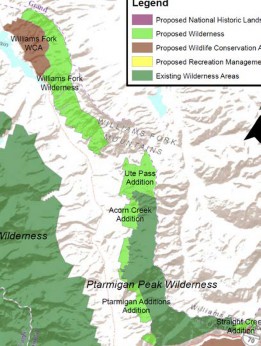

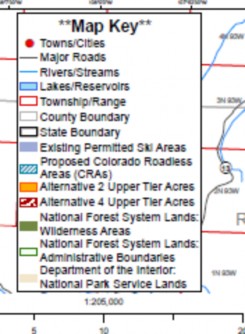

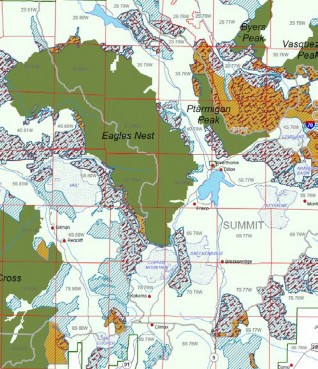

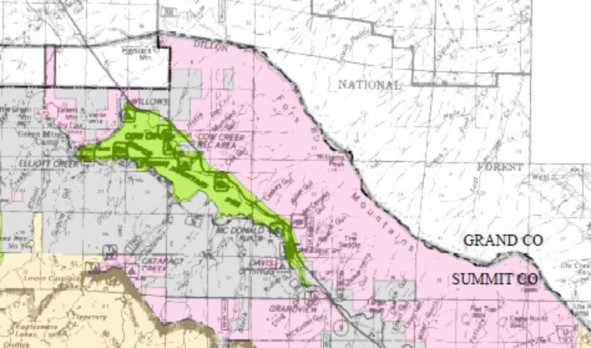

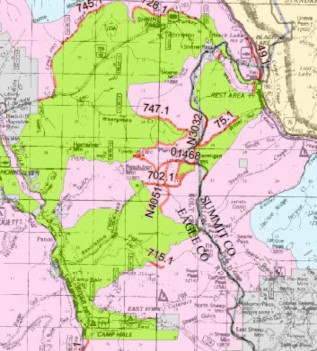

In the Roadless Rule process, generally two categories of management inventory were explored, which were Colorado Roadless areas and Upper Tier Roadless areas. In an Upper Tier roadless area, management was closer to a Congressionally Designated Wilderness and in Colorado Roadless Area management direction was moved towards higher levels of usage and flexibility. Under Alternative 2 (preferred) the designation of Upper Tier Roadless management is reflected in areas highlighted in yellow on the map below and alternative 4 of the Proposal provided a more extensive acreage of areas for possible upper tier designation, which is reflected in the red freckled areas on the map below. The stark differences between the scope of alternative 2 and alternative 4 of the inventory are reflected in the map below:

The Organizations must note that almost EVERY area now proposed to be Wilderness was reviewed under Alternative 4 of the Roadless Rule EIS and found to be unsuitable for this lower level of protection and management of an Upper Tier management designation. In the site-specific descriptions of each of these areas, a detailed discussion of the reasons for designation of these areas either as CRA or Upper Tier was provided. The Organizations must question any assertion that these areas are suitable for Wilderness designations, when these areas were recently inventoried and found unsuitable for the lower level of protection provided by an Upper Tier designation. Any assertion of factual basis for such management would not be supported by the extensive site-specific inventory and review that was created as part of the Colorado Roadless Rule development.

5. Site-Specific Concerns.

The Organizations are providing the following site-specific comments to address the significant lost recreational opportunities that would immediately occur with the passage of the Proposal. The Organizations are opposed to the loss of these opportunities for the following reasons:

- There is simply no offsetting protection or release of recreational areas frompossible Wilderness designations in other parts of the Legislation;

- Only a small portion of the WRNF is even suitable or available for multiple userecreation as exemplified by the fact that only 7% of the WRNF is suitable andavailable for OSV travel; and

- These are important recreational opportunities that are heavily used due tolimited opportunities in the Proposal area.

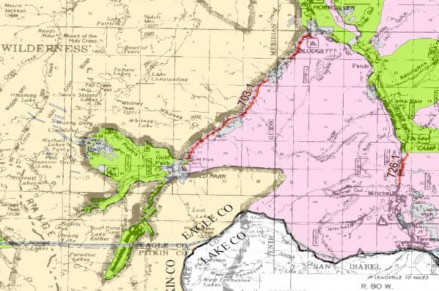

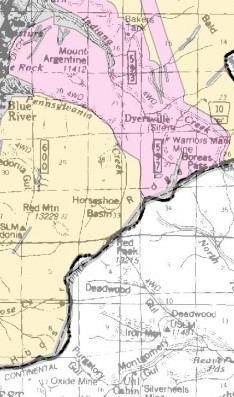

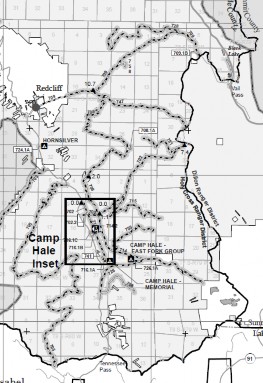

The Organizations believe the source of the following maps and information is highly relevant as each of the summer Motor Vehicle Use Maps is highlighted to identify lost trail networks reflects current management on that Ranger District and the Winter OSV Suitability information comes from the White River National Forest recent Winter Travel Planning Process. On the winter suitability maps, green areas are designated for open winter usage, and pink areas are future expansion areas for OSV travel, where travel is currently restricted to designated routes in the area. OSV closure areas are identified in tan, but no portion of the Proposal area lies outside existing Wilderness in areas which are closed to OSV travel.

5(a). Ptarmigan Peak (§3a1) & Williams Fork (§4) & Williams Fork Wildlife Conservation Area (§7)

The Organizations are opposed to the lost opportunities in the Williams Fork WCA, Ptarmigan Peak and Williams Fork Wilderness additions due to the loss of more than 20,000 acres of motorized recreational areas. This closure would include the loss of a significant number of miles of heavily used currently authorized summer trail in these areas, as exemplified by the Cow Creek North and South networks immediately outside the Cow Creek and other campgrounds immediately adjacent to the trailheads, Route 2950.5a coming over from the ARNF and Route 2840. The entire area is also a future expansion area for OSV travel and also includes a significant important open riding area.

WRNF Winter OSV suitability

The Organizations must specifically mention that the alleged benefit that is asserted to be provided in the Williams Fork WCA is of no value to the multiple use commuity, as this alleged benefit is a ceiling for mileage and routes in the area created in §7b1 of the Proposal. Unfortunately, there is no corresponding floor for trail mileage in the areas, and such a mileage floor would be highly valued by the Organizations. As a result, no additional routes can ever be built in these areas but all routes in the area could be lost. The Organizations must question any assertion of value to mutiple use interests from these provisions, as the Organizations are simply unable to find the asserted benefit. With designation of these areas under the Proposal, signficiant negative imapcts to existing recreational access would occur.

The Organizations are also very concerned with setting a precedent allowing for the automatic change of an area to Wilderness with the mere passage of time. The Organizations are not aware of any precedent for automatic change of lands to Wilderness designation merely with the passage of time. Adopting such a principal could set a dangerous precedent moving forward and the Proposal provides no requirement that mitigation measures be completed prior to moving to the Wilderness designation. Mitigation measures can frequently take more than the 10 years to complete but the Proposal allows for a mere 180 day period for inventory and analysis of this issue. This is problematic and would result in significant new analysis to be undertaken by land managers that are already struggling to provide for basic operations due to limited budgets and funding.

The Organizations would note that pursuant to §3e the Colorado Wilderness Act of 199336 that designated the Ptarmigan Peak area as Wilderness, there were to be “no buffer zones” around the Ptarmigan Peak Wilderness. Despite the clear direction of this Legislation, discussions have continued about expanding the Ptarmigan Peak Wilderness since the passage of the 1993 Legisaltion. This exemplifies why the Organizations place little value in the “no buffer” provisions in the current Propsoal, as this discussion highlights the fact these provisions are some of the most ingored provisions of federal law ever passed.

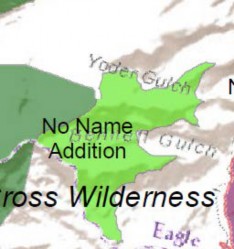

5(b). No Name Wilderness – §3a23

The adoption of the Proposed management in the No Name area would result in the immediate loss of more than 3,900 acres of future OSV expansion area. While no routes would be immediately lost for summer travel, the Organizations have significant long-term concerns due to proximity of the existing routes to new Wilderness areas. It has been the Organizations such proximity never resolves management issues for the areas but rather creates conflict due to the fact that those seeking the solitude of the Wilderness immediately raise user conflict concerns due to the proximity of multiple use. While the Proposal does provide for “no buffers” in management, but in other areas where no buffers have been provided such protections have been completely useless in addressing user conflict and future expansions. Our concerns with no buffer type legislation are identified previously.

2014 Summer MVUM

Winter OSV suitability currently

Management under the Proposal

The Organizations are opposed to this portion of the Proposal as the entire No Name area is a winter expansion area for OSV travel and would convert FSR703, which is currently a groomed route through an important open riding area to a cherry stem into an important OSV area for winter usage as there would now be Wilderness on both sides of the route. That would put the route and inholding of open riding area in the Wilderness immediately at risk due to the conflicts in usage of the area. That is simply unacceptable.

Summer motorized recreation would also be significantly put at risk from these new Wilderness areas, as FSR703 is the Holy Cross City route that is consistently identified as one of the top ten OHV routes in the country. While all routes are important to the multiple use community, the value of the Holy Cross City route to especially the full size 4×4 community cannot be overstated. Additionally, the eastern boundary of the No Name expansion area is a currently designated summer route and expanding the boundary to the route would result in immediate conflict between usages on that route. Given the value of these routes, any new Wilderness could never be supported in these areas due to possible challenges to these routes in the future. Again, a “no buffer” type protections do not resolve that type of concern in the least and there is no benefit in other areas to arguably even discuss a risk to important routes that could result from the passage of the Proposal.

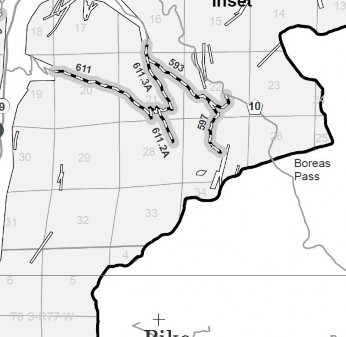

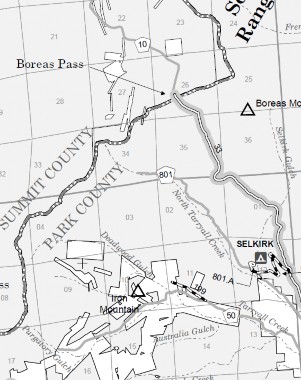

5(c). Hoosier Ridge Wilderness(§3a24)

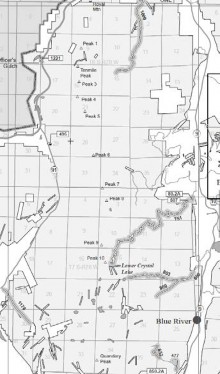

The Organizations are again concerned regarding the long-term opportunities in this area due to proximity of the Proposed Wilderness to heavily used areas immediately surrounding the Hoosier Ridge Wilderness area, including opportunities on both the Dillon and the South Park Ranger Districts generally surrounding the Boreas Pass Area. These adjacent areas are represented in the MVUM identified below:

2014 Summer MVUM- Dillon RD

2014 Summer MVUM – South Park RD

Current OSV Suitability

Boreas Pass area is a major multiple use summer destination area. Given the proximity of the expanded Wilderness boundary to highly used routes, conflict between these uses would be a concern. Again, “no buffer” language has proven to be highly ineffective in addressing these types of concerns previously. Our concerns about the Hoosier Ridge area are compounded by the fact that the Pennsylvania Gulch area, immediately to the north of the Hoosier Ridge area is again another important future expansion area for OSV travel that possess exceptionally high-quality riding opportunities that could not be put at risk with a Wilderness expansion into areas adjacent to Pennsylvania Gulch.

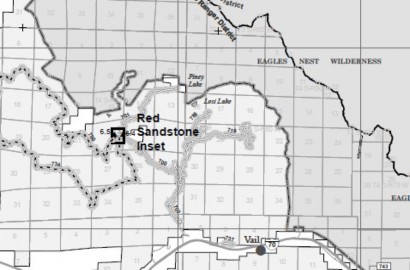

5(d). Spraddle Creek Wilderness area additions -§3(a) (26)

The Spraddle Creek Wilderness contains an extensive high-quality summer trail network for motorized and bicycle community centered around FSR 700/719 that would be lost with passage of the Proposal. These are important routes due to their proximity to local population centers.

2014 Summer MVUM

Current Snowmobile Suitability

Management under the Proposal

The potential Spraddle Creek Wilderness represents an important open riding snowmobile opportunity area that would be lost immediately in addition to the future expansion areas for OSV travel. Many OSV users believe that closure of the eastern portions this area in recent travel planning was due to 10th mtn. hut in area. Almost all 10th mtn. division huts now have a buffer area, as a result of recent planning which has resulted in the long-term loss of motorized opportunities around huts. Users are very sensitive to additional lost opportunity around any of the huts. Additionally, the snowmobile community worked hard with the USFS in recent planning to establish a boundary that was easily enforceable in the area for snowmobile usage (currently on top of a cliff). Expanding the Wilderness would again move the boundary into an area where enforcement would be difficult at best and probably result in a large amount of conflict and enforcement expense.

Expansion of Wilderness in this area could prohibit OSV usage connecting Spraddle Creek area to Spring Creek groomed network north of Eagles Nest Wilderness. This type of a connection was left as a long-term option in the recent travel plan for the area. We understand there is some conflict over exact location of Wilderness boundary and any groomed route developed in the area in the future. This is a major concern as any possible routes that could connect the areas are limited due to rugged topography of the area. A connection of Spraddle Creek and Spring Creek areas would be highly valued by OSV community as currently Spring Creek trailhead is a lengthy drive (more than 1 hour) on US 9 north of Frisco. With this connection, access to the Spring Creek area would be a short drive outside Frisco.

Expansion of the Spraddle Creek Wilderness areas would result in the immediate loss of motorized routes 786 and 719 that currently exist in the area and dead-end at two scenic overlooks. With the addition of the Spraddle Creek Wilderness access to these overlooks would be lost and 786 and 719 outside the Wilderness would be at risk for closure moving forward as these trails would now just dead-end at the Wilderness boundary. We are concerned that the proximity of a possible groomed route/existing designated summer route and this Wilderness boundary. Our concern is the expanded boundary would result in significant conflict between users and also present a major management issue for the USFS due to increased signage etc. The close proximity of these management areas has resulted in significant conflict in other areas and as we have expressed previously, the Organizations have SERIOUS concerns about the effectiveness of “no buffer” type management standards.

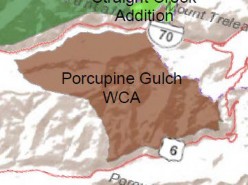

5(e). Porcupine Gulch Wildlife Conservation area – §4

The Organizations are simply flabbergasted that the 8,176 acres identified as the Porcupine Gulch Protection area is being proposed for loss to multiple use recreation, as this area was recently the basis of a multiple year collaborative process involving the USFS, Summit County Commissioners, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Hikers, Mountain Bikers, Wilderness Advocates, Colorado Mountain Club, the Quiet Use coalition, local land owners and motorized users. This multiple year collaborative effort resulted in a consensus position regarding the future management of the area identified as the Tenderfoot Trail Proposal, which was then moved forward with minimal public opposition or concern. In addition to these active participants the Organizations recall those proceedings moving forward with the support of both Senator Bennett and Congressman Polis offices.

All detailed information regarding the Tenderfoot Trail project can be found here

https://data.ecosystem-management.org/nepaweb/nepa_project_exp.php?project=34502

Subsequent to the finalization of the EA for this project in 2012, more than 30 miles of trails have been closed and rehabilitated, 11 miles of sustainable single track were created and extensive new parking has resulted from the almost $1 million in partner grant funding that has been provided to implement the Tenderfoot Plan. This trail proposal has become a shining success story in the area and a model for resolving contentious planning issues in high use areas. Despite the success of the Tenderfoot project, the Porcupine WCA proposes to prohibit motorized and mechanized travel in the area. That is simply offensive to the collaborative process that has been undertaken and would provide a significant barrier to such collaborative efforts ever being undertaken again in the future.

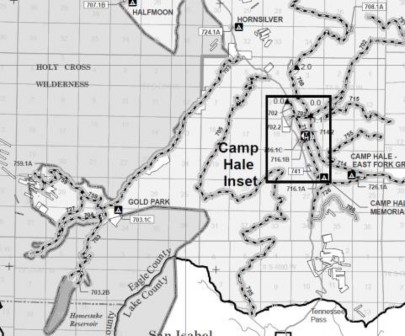

5(f). Camp Hale National Historic Landscape §8

While the Organizations welcome the heightened importance of identification and removal of unexploded ordinance in the proposed Camp Hale National Historic Landscape provisions and that OSV usage is at least identified as a characteristic of the area, there is no additional protection of existing OSV usage provided in the Legislation. The Organizations simply cannot support identification of basic safety concerns in the area and then not providing protections of existing recreational access to the area.

In addition to providing no protection for OSV usage in the Camp Hale area, the Proposal provides no recognition of the important multiple use summer trail opportunities is provided for in the Legislation despite the extensive trail network that is currently authorized in the Camp Hale area.

2014 MVUM

OSV Suitability and groomed routes

Clearly removal of unexploded ordinance could result in conflict between mitigation activities and recreational usage of trails in the vicinity of these activities. With the statutory elevation of ordinance removal for safety reasons, the Organizations can clearly see recreational access being put at risk at least during the term of removal. Managers could easy prohibit access after running out of funding to undertake the ordinance remediation in the area simply to attempt to comply with safety-based provisions of the Legislation. This is simply unacceptable as both short and long-term access to the area must be identified and protected and has not been.

The Organizations concerns about long term route loss from elevation of public safety concerns involving unexploded ordinance are compounded when the grant of Federal funding provided for in the Proposal is reviewed. The Organizations submit that any assertion that water impoundment facilities could be improved, historical interpretation sites created and a complete inventory of ordinance in the Camp Hale area with associated NEPA required for removal could be completed for the mere sum of $5,000,000 is simply without any basis in fact. The Organizations submit that the funding provided managers would be hard pressed to complete one of the three goals, little lone all three. With the provided imbalance in funding with goals and objectives for management of the area, clearly protection of all usage of the area would be critical in insuring opportunities are not lost in the area.

While the interest in unexploded ordinance is appreciated, the provisions of the SMA fall well short of anything that could be supported by the Organizations. To provide any value to the motorized community in the Legislation for this area, a floor for motorized travel must be provided and the importance of motorized access for both summer and winter motorized recreation at existing levels must be provided for.

5g. Ten Mile Recreation/Wilderness area §5

The Organizations submit that the designation of the Ten Mile Recreation Area would result in the loss of 16,996 acres for multiple use as multiple use recreation is not even a characteristic of the area. This is another area where important multiple use recreational opportunities are currently existing but no protection for these opportunities is provided by the Proposal. Rather than protecting these important opportunities, existing opportunities and future expansion areas would be permanently limited from expansion and additionally provided no protection from closure in the future as other priorities for the use of the Recreation area would be established by the Proposal.

2014 MVUM

Over the Snow Suitability

The Organizations opposition to the designation of these areas is based on the fact that no multiple uses are even identified as a characteristic of the area to be protected or reserved, while certain other recreational activities are advanced as characteristics of the area. Additionally, multiple use access is capped at current levels, despite a large portion of the area being available for OSV expansion. The Organizations are unable to see any benefit to the multiple use recreation community from designation of this area as multiple use access would be immediately capped and then put at risk of loss due to the elevation of other interests in the area as management priorities.

5h. The Proposal provides no benefits or protections for multiple use recreation to offset risks and losses in new Wilderness areas created and previous commitments must be honored.

The Organizations must note the significant differences between the current Proposal and the Hermosa Watershed Legislation. The current Proposal provides for extensive loss of mileage and acreage to multiple use interests but no other areas are released from possible future designation and protected for multiple use. The Proposal also puts numerous other areas at risk for long term loss due to the proximity of these areas to new Wilderness areas, no additional protections are provided in the Proposal for the areas put at risk for long term loss. As noted previously, “no buffer” type management standards provided in previous Wilderness Legislation have been largely ignored. While the Organizations believe that the ineffective nature of “no buffer” type protections is concerning, the lack of balance in previous Wilderness Legislation is problematic. Even when more defined and concrete benefits to the multiple use community have been provided in previous Wilderness legislation, these benefits have never been implemented.

An example of this issue would be the commitment to reopen the Rollins Pass Road that was made in § 7(b) the James Peak Wilderness Expansion and Protection Act of 2002. The Rollins Pass Road Language was in addition to the “no buffer” language provide in the James Peak Legislation. Not only has there been no carry through on the legal obligation to reopen James Peak Road, this legislation provides yet another example of the ineffective nature of the “no buffer” language as both of the Wilderness areas involved in the James Peak proposal have been the basis of ongoing efforts to again expand these Wilderness areas despite the No buffer language. Reopening of Rollins Pass road, as has been required by federal law would be a significant gesture to the multiple use community that implementation of commitments made in Wilderness legislation is as important as passage of the original legislation.

6. Conclusion.

After a detailed review of the proposal, the Organizations have concluded that every area expanded or created in the Proposal would result in significant lost recreational opportunities for the overwhelming portion of visitors to the Proposal area, both currently and in the future. While there are significant lost opportunities there is also no additional protections for multiple use routes that might remain outside the Wilderness areas and no new areas are designated for OHV recreation. Additionally, frustrating any discussions around balance in the Proposal is the fact that earlier commitments made in Wilderness legislation in Congressman Polis district remain unfulfilled. Reopening Rollins Pass Road would be a significant step in meaningfully addressing usages in the Proposal. If commitments are not honored, what is the value in working towards more balance in any Proposal. The Organizations still fail to understand the management concerns or perceived threats that are driving the discussion around the need for additional protection of these areas.

The Organizations have been visiting with your Office staff attempting to find some type of consensus position that we could support around these areas, but it appears those discussions have not been fruitful, as this version of the Proposal is the worst version of the Proposal the Organizations have seen in a long time. This is highly frustrating as the Organizations were actively involved in the development of the Hermosa Watershed Legislation where large and diverse community support was developed around the Hermosa Legislation and a wide range of protections for a diverse group of users was achieved. The Organizations had hoped the Hermosa legislation was a new model for developing land use legislation but that does not appear to be the case.

In an effort to continue to discuss Wilderness and related management protections in the Eagle and Summit County areas, the Organizations have included our draft discussion of areas we would be interested in seeing additional protection for in federal legislation. Please feel free to contact Scott Jones, Esq. if you should wish to discuss any of the issues that have been raised in these comments further. His contact information is Scott Jones, Esq., 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont Colorado 80504; phone 518-281-5810; email Scott.jones46@yahoo.com

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

COHVCO/TPA Authorized Representative

CSA President

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

Cc: Senator Cory Gardner

- See, USDA Forest Service; National Strategy for a Sustainable Trails System; December 30, 2016 at page 2.

- See, USDA Forest Service; National Visitor Use Monitoring Survey Results – National Summary Report – data collected FY2012 through FY2016; December 2016 at pg. 10.

- See, USDA Forest Service; Visitor Use Report; White River NF; USDA Forest Service Region 2 National Visitor Use Monitoring Data; Collected through FY 2012 Last Updated January 26, 2018 at pg. 9.

- See, National Forest Foundation website at https://www.nationalforests.org/our-forests/find-a-forest/white-river-national-forest accessed February 21, 2018.

- See, USDA Forest Service; Tkacz et al; 2013-2027 National Insect and Disease Forest Risk Assessment; 2015 at pg. 36.Hereinafter referred to as the “USDA Risk Assessment”.

- See, USDA Risk Assessment at pg. 50.

- See, USDA Risk Assessment at pg. 51.

- A complete copy of this presentation and related documents is available athttps://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/fhm/fhh/fhh_16/CO_FHH_%202016.pdf

- http://csfs.colostate.edu/2017/02/15/800-million-standing-dead-trees-colorado/

- 2016 Forest Health Report at pg. 61

- 2016 Forest Health Report at pg. 24

- 2016 Forest Health Report at pg. 24

- 2016 Forest Health Report at pg. 24

- See, 2016 Forest Health Report at pg. 5.

- See, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; Review of the Forest Service Response to the Bark Beetle Outbreak in Colorado and Southern Wyoming; A report by USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region and Rocky Mountain Research Station at the request of Senator Mark Udall; September 2011 at pg. 5.

- See, Udall Forest Health Report at pg. I

- See, Colorado State Forest Service; 2011 Report on the Health of Colorado’s Forests; at pg. 9.

- See, Colorado State Forest Service; 2011 Report on the Health of Colorado’s Forests; at pg. 11.

- See, Colorado Parks and Wildlife; 2015 Colorado State Wildlife Action Plan at pg. 279.

- This list of species includes: Albert Squirrel; American Marten; Hoary Bat; Snowshoe Hare and Luck spine moth.

- See, USFWS; Dr. Michael Young; Greenback Cutthroat Trout; A Technical Conservation Assessment; February 6, 2009 at pg. 3.

- See, Young @ pg. 20.

- See, Young @ pg. 21.

- See, USDA Forest Service; Pacific Southwest Region Research Station; Forest Service Response to Elevated Tree Mortality; prepared at the request of California State Association of Counties; March 24, 2016 at pg. 14.

- Photo included with application of Divide Ranger District application for maintenance in the Weminuche Wilderness to Colorado State Trails Program for maintenance funding.

- See, USFS presentation of Scott Haas, Region 2 Recreation Coordinator at the 2016 Colorado OHV Workshop. Full copy of presentation available on request.

- See, Douglas Macintyre; “American Ghost Towns of the 21st Century”; The Wall Street Journal; April 11, 2011

- See, USDA Forest Service; “White River NF- Job and Income Contributions for 2014 at a glance”; September 2016 A complete copy of this research is available here https://www.fs.fed.us/emc/economics/contributions/documents/at-a-glance/published/rockymountain/AtaGlance-WhiteRiver.pdf

- See, Department of Commerce; Bureau of Economic Analysis; “Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account: Prototype Statistics for 2012-2016”; February 14, 2018 at pg. 2.

- See, USDA Forest Service; National Forest Support a Recreation Economy- a complete study copy is available here: http://blog.nwf.org/2014/07/national-forests-support-recreation-economy/

- See, Holmes & White; National & Community Market Contributions of Wilderness; Society & Natural Resources; An International Journal; Volume 30 2017

- See, UDSA Forest Service; White & Stynes; Updated Spending Profiles for National Forest Recreation Visitors by Activity; Joint venture between USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station and Oregon State University; November 2011 at pg. 6.

- See, USDA Forest Service, National Visitor Use Monitoring; “National Visitor Use Monitoring Survey Results; National Summary Report; Data collected FY 2012 through FY 2016”; 2016 at pg. 1.

- See, USDA Forest Service; 36 CFR Part 294 Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation; Applicability to the National Forests in Colorado; Final Environmental Impact Statement; May 2012 pg. 19

- See, USDA Forest Service; National Visitor Use Monitoring Results; White River National Forest; Round 3; last updated January 26, 2018 at pg. 9.

- See, HR 631 of 1993