Gila National Forest

Att: Plan Revision

3005 E. Camino del Bosque

Silver City, NM 88061

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the comments of the Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) with regard to the Gila National Forests Resource Management Plan revision (“the Proposal”). Prior to addressing the specific concerns on the Proposal, THE ORGANIZATIONS believe a brief summary of the Organization is necessary. The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. TPA is commenting on the Proposal as many of our members have a long history of enjoying the multiple use recreational opportunities on the Gila NF in addition to their property ownership in areas adjacent to the Gila NF. The Off-Road Business Association(“ORBA”) is a national not-for- profit trade association of motorized off-road related businesses formed to promote and preserve off-road recreation in an environmentally responsible manner and appreciates the opportunity to provide comments on this issue. One Voice is a non-profit national association committed to promoting the rights of motorized enthusiasts and improving advocacy in keeping public and private lands open for responsible recreation through strong leadership, advocacy, and collaboration. One Voice is a partner of ORBA and provides a unified voice for grassroots motorized recreation organizations through a national platform that represents the diverse off-highway vehicle (OHV) community. Collectively in these comments TPA, ORBA and One Voice will be referred to as the Organizations.

The Organizations comments will be focused on two issues: 1. Generally restrictive standards that are being placed on the transportation network in the new RMP that could conflict with projects in the future; and 2. The direct conflict of proposed management standards around the CDT and other National Trails System designated routes with relevant federal law. While the three national recreation trails that are currently designated on the Gila do not allow for motorized usage, the Organizations submit that national recreation trails could be designated on the Gila in the future for the benefit of other users, as this is specifically allowed under the NTSA, the forest plan should not standard in contradiction of such a designation and in conflict with the clear intent of Congress on this issue. The Organizations submit these are issues that must be resolved prior to release of the final version of the RMP in order to create a high-quality planning document that will remain relevant over the life of the Proposal and in compliance with relevant federal laws.

The Organizations are very concerned that as exclusionary corridors around the CDT and other National Trail System Act routes have moved forward in resource planning, often these corridors immediately become non-motorized corridors without addressing existing usages of these corridor areas as exemplified by the multiple forests in California moving forward with winter travel planning and the adoption of the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan in Southern California by the BLM. While corridors are immediately to be applied in the preferred alternative, at no point is there any analysis of possible impacts to existing usages is even mentioned despite numerous requirements in federal law requiring a specific review of these types of impacts.

1. Flexibility must be provided for National Recreation Trail designations in the future.

As previously mentioned, The Organizations are very concerned that the Proposal provides for management that conflicts with federal laws, mainly that the Proposal prohibits actions that are specifically allowed in federal law. The Proposal provides as follows:

“1) National Recreation Trails provide a variety of opportunities for non-motorized recreation as well as a diversity of experiences with different levels of solitude, remoteness, and development.”1

The Organizations can find no basis for the restriction of a national recreation trail to only non- motorized purposes and would note that while national scenic trails are alleged to be non- motorized, there are many exceptions to such a standard and 20% of the CDT is currently located on public roads. The scope of use on all national trails is clearly provided in the National Trails System act as follows:

“(j) Types of trail use allowed

Potential trail uses allowed on designated components of the national trails system may include, but are not limited to, the following: bicycling, cross-country skiing, day hiking, equestrian activities, jogging or similar fitness activities, trail biking, overnight and long-distance backpacking, snowmobiling, and surface water and underwater activities. Vehicles which may be permitted on certain trails may include, but need not be limited to, motorcycles, bicycles, four-wheel drive or all-terrain off-road vehicles. In addition, trail access for handicapped individuals may be provided. The provisions of this subsection shall not supersede any other provisions of this chapter or other Federal laws, or any State or local laws.” 2

This simply must be resolved. This management flexibility regarding the road and trail network will also be necessary to address management challenges that are facing the forest, such as declining forest health. Both the US Forest Service and New Mexico State Forest Service recently jointly identified:

“These issues emphasize the continued need for managers to develop and conduct silvicultural treatments to reduce tree density on much of the state’s forests and woodlands. Insect infestations and forest disease complexes (many interacting factors) are nearly impossible to suppress or control once in place; therefore, prevention is the proper forest health strategy. Prevention is achieved by restoring the capacity of a forest ecosystem to resist disturbance, recover quickly, and retain vital structure and function. This is called forest resiliency. Without resilient forests, damage will continue until the responsible agent(s) run out of hosts.” 3

The Organizations is aware that often the lack of basic access to public lands due to management restrictions is a major management challenge when addressing large scale issues, such as poor forest health or drought. Providing a balanced management goal and objective for the Forest would allow for future managers to address challenges from population growth and meaningfully address challenges to the Forest that simply might not even be thought of at this time. Why is The Organizations concerned? Too often recreational access to public lands is lost when maintenance cannot be performed in a cost-effective manner. Adding additional management standards that will at a minimum need an additional round of NEPA planning to address future management challenges simply makes no sense.

2a. CDT corridors conflict with federal law.

The Organizations must express serious concern regarding the direct conflict between federal law and management standards and guidelines proposed for both the direct foot print and areas surrounding the Continental Divide Scenic Trail. While there are numerous new management standards provided for in the Proposal, there is absolutely no analysis of possible impacts to existing usages from these management changes or the fact that many of the existing usages are protected under federal law. The Proposal starts with the implementation of a .5-mile corridor around the entire CDT as follows:

“Viewsheds from the CDT have high scenic values. The foreground of the trail (up to 0.5 mile on either side) is naturally-appearing. The potential to view wildlife is high, and evidence of ecological processes such as fire, insects, and diseases exist.”4

Under the Proposal, the following desired conditions would guide the CDT:

“The CDT is a well-defined trail that provides for high-quality, primitive hiking and horseback riding opportunities, and other compatible non-motorized trail activities, in a highly scenic setting along the Continental Divide.”5

As discussed in subsequent portions of these comments, the CDT plan currently recognized that 20% of the CDT is currently located on motorized roads. While the CDT Plan only addresses levels of road occupancy, The Organizations is aware of extensive portions of the CDT that are currently located on motorized trails currently provided for in the travel management process and are again specifically protected under federal law. In addition to the desired conditions, the Proposal provides for the following management standard as follows:

“Motorized events and motorized special use permits shall not be permitted or authorized on the CDNST.”6

The Proposal continues with Guidelines that provide as follows:

“4) In order to promote a non-motorized setting, the CDT should not be permanently re-located onto routes open to motor vehicle use.

8) In order to promote a naturally appearing, non-motorized setting, constructing temporary or permanent roads or motorized trails across or adjacent to the trail should be avoided unless needed for resource protection, private lands access, or to protect public health and safety.” 7

Again, no basis for the need for these types of standards is provided and the Proposal provides no analysis of possible impacts that might result from the new management standards The Organizations are concerned that according to the CDT management plan 20% of the CDT is currently located on motorized roads, and a higher level of the CDT is located on motorized trails and even more trails cross the CDT but are never collocated on the trail footprint but would be directly impacted by exclusionary corridor type management. Given the direct conflict with both federal law and general planning goals and objectives for the Gila NF and the complete failure to analyze possible impacts from these management decisions as required by NEPA, The Organizations must question why this type of management standard would be explored.

2b. Continental Divide Trail management and corridor usage must be governed by multiple use principals.

The Organizations are aware of extensive discussions and pressure from certain interest groups surrounding the management of National Scenic Trails and National Historic Trails on numerous other forests, as exemplified by discussions around the Pacific Crest Trail as it travels through the Lassen, Tahoe, Stanislaus and Plumas National Forests in California and similar standards are now proposed on the Rio Grande and GMUG in Colorado. While these discussions are often passionate and filled with an artificial urgency to save the trail from some unknown threat, this position simply lacks any basis as it conflicts with the direct language of the National Trails System Act, the intent of Congress in passing the NTSA, the specific language of the Trail related NEPA plans and numerous other Executive Orders regarding recreation and cost benefits analysis. The Organizations is concerned that as the concept of a corridor moved forward on the Gila NF, multiple use concepts and existing routes were immediately excluded under the new Forest Plans.

There are numerous standards that are proposed in the Gila NF RMP that could result in exclusionary corridors and restricted access being developed in subsequent site-specific planning around the CDT or simply expanded into the preferred alternative of the RMP. Often pressure and efforts of groups asserted that national trails system routes must be non-motorized under the National Trails Act are based on incomplete or inaccurate reviews of the National Trails System Act. These inaccurate summaries can be easily achieved due to the poor drafting of the NTSA and the following provisions are included in the hope of bringing balance to these discussions. Unfortunately, these incomplete and conflicting summaries have now been included in USFS Guidance on NTSA designated routes. The Organizations must briefly address the management history of the Continental Divide Scenic Trail and the specific statutory provisions addressing both the CDT and the usage of public lands in areas adjacent to the CDT. Prior to addressing the clarity of the current NTSA, a review of the intent of Congress and competing interests at the time of passage of the NTSA is relevant. Corridors excluding usages violates the NTSA directly, minimizes values, fails from a cost/benefit perspective and economic contribution analysis and will lead to unprecedented conflicts between users that simply does not exist at this time.

The management of NTSA corridors and routes has a long and sometime conflicting management history when only summaries of legislative language is reviewed but significant clarity in Congressional intent for management of routes and corridors is provided with the review of Congressional reports provided around passage of the NTSA. Additionally, every time Congress has spoken regarding these alleged conflicts the NTSA has been amended to include stronger language in favor of multiple use and opposing corridors. Extensive background regarding multiple uses of corridors and trails designated under the NTSA was originally addressed in House Report 1631 (“HRep 1631”) issued in conjunction with the passage of the NTSA in 1968. A complete copy of this report is submitted with these comments for your convenience. While there are numerous Congressional reports referenced in the 2016 USFS CDT guidance, many of which have not been provided to the Congressional offices for release to the public, HRep 1631 is simply never mentioned despite it being a foundational document in the discussion. Such conflicts should be problematic for managers seeking to implement recommendations of USFS Guidance on the NTSA as Congress has repeatedly had the opportunity to require exclusionary corridors around NTSA routes but has consistently moved towards more clarity in addressing multiple usage of these areas.

HRep 1631 provides detailed guidance regarding the intent of the Legislation, and options that Congress declined to implement in the Legislation when it was passed. It is deeply troubling to THE ORGANIZATIONS that USFS guidance relies on numerous legislative documents that were related to amendments no longer even in the NTSA and many of which are unavailable to the public,8 but this highly relevant legislative document is never addressed in the USFS Guidance. Further drawing the USFS Guidance on this issue into question is the fact that while guidance asserts that unfiled Congressional reports that have been superseded remain controlling, some of the most important land management legislation passed last century is overlooked as well. While the NTSA was passed in 1968, the Federal Lands Policy and Management Act of 1976 is simply never addressed in USFS guidance. The Organizations simply have no idea how FLPMA could not directly relate to the management of any corridor around the CDT.

HRep 1631 provides a clear statement of the intent of Congress regarding multiple usages with passage of NTSA in 1968, which is as follows:

“The aim of recreation trails is to satisfy a variety of recreation interests primarily at locations readily accessible to the population centers of the Nation.”9

The Organizations note that satisfaction of a variety of recreation interests on public lands simply is not achieved with the implementation of any width corridor around a usage or trail even before FLPMA was adopted into federal law. Rather than providing satisfaction for all uses, implementation of mandatory corridors will result in unprecedented conflict between users. This simply must be avoided.

While HRep 1631 is not addressed in 2016 USFS CDT guidance, the direct conflict of the agency guidance and this report and FLPMA simply cannot be overlooked. Much of the information and analysis provided in HRep 1631 is highly relevant to the authority of USFS guidance assertions that ½ mile corridors is mandatory or even recommended. HRep 1631 clearly and unequivocally states Congress declined to apply mandatory management corridors of any width in the Legislation. HRep 1631 states:

“Finally, where a narrow corridor can provide the necessary continuity without seriously jeopardizing the overall character of the trail, the Secretary should give the economics of the situation due consideration, along with the aesthetic values, in order to reduce the acquisition costs involved.”10

Congress also clearly identified that exclusionary corridors would significantly impair the ability of the agencies to implement the goals and objectives of the NTSA as follows:

“By prohibiting the Secretary from denying them the right to use motorized vehicles across lands which they agree to allow to be used for trail purposes, it is hoped that many privately owned, primitive roadways can be converted to trail use for the benefit of the general public.”11

HRep 1631 clearly addresses the intent of Congress, and the internal Congressional discussions regarding implementation of the NTSA provisions for the benefit of all recreational activities as follows:

“However, they both attempted to deal with the problems arising from other needs along the trails. Rather than limiting such use of the scenic trails to “reasonable crossings”, as provided by the Senate language, the conference committee adopted the House amendment which authorizes the appropriate Secretaries to promulgate reasonable regulations to govern the use of motorized vehicles on or across the national scenic trails under specified conditions.”12

Rather than conveying the clear intent of Congress to avoid corridors as a part of management of an NTSA route, on page one of the 2016 CDT guidance clearly states that such a corridor is the preferred management tool, stating as follows:

“The CDT corridor/MA should be wide enough to encompass the resources, qualities, values, associated settings and primary uses of the Trail. The 0.5-mile foreground viewed from either side of the CDT must be a primary consideration in delineating the CDT corridor/MA boundary (FSM 2353.44b (7)).”13

The Organizations submit that the intent of Congress was clear when the NTSA was passed in 1968, and the clarity of managing the trail footprint and any areas around a trail was clearly impacted by FLPMA, which is the foundation of the concept of Resource Management Plans and area specific goals and objectives. The primacy of FLPMA requirements over NTSA provisions was confirmed again by Congress in 1983, when the NTSA was completely reconstructed by Congress with the passage of PL 98-11. This revision removed any concept of the corridor from the NTSA and clearly identified that multiple use principals and FLPMA were to govern NTSA routes and areas. Again, this is simply never addressed in USFS guidance and is directly contrary to any concept of a corridor being implemented in forest level planning.

The Organizations are simply unable to theorize any situation where the intent of Congress in passing the NTSA in 1968, the subsequent adoption of FLPMA and the 2016 CDT guidance can be reconciled, as Congress specifically stated that corridors should not be applied and managers retain authority to address site specific issues and challenges. This is deeply concerning given the fact that if Congress has specifically looked at a management tool and specifically declined its application, any implementation of such a tool in management is problematic. This type of direct material conflict is not mitigated with the passage of time especially when the clearly stated intent of Congress was to satisfy a variety of recreational interests with the passage of the NTSA. The Organizations vigorously assert that only those interests protected by the corridor would be satisfied with a corridor, and this must be avoided.

2c. Congress has consistently declined to require minimum exclusionary corridors around NTSA trails.

Management of the CDT is specifically governed by the National Trail System Act (NTSA) which specifically addresses multiple usage of areas adjacent to trails and how these multiple use mandates will relate to management of the trail. The NTSA provides as follows:

“In selecting the rights-of-way full consideration shall be given to minimizing the adverse effects upon the adjacent landowner or user and his operation. Development and management of each segment of the National Trails System shall be designed to harmonize with and complement any established multiple use plans for that specific area in order to insure continued maximum benefits from the land.”14

The Organizations believe that Congress was very clear in these provisions, as they clearly stated maximum benefits from the land and harmony with multiple use planning was the objective. The Organizations submit that maximum benefits from the land as a management standard is a FAR more encompassing standard of management than maximizing benefit of the trail or an area to the users of the trail. Subsequently creating management standards that violated these provisions would be precluded as well as all of the management concerns Congress sought to remove with the acquisition requirements remain valid management standards on the NTSA route.

While the NTSA does provide that multiple uses are not allowed on an NTSA route in Wilderness Areas, National Wildlife Areas, and National Parks among other areas where such usage would be prohibited in 1968, the NTSA makes no mention of prohibitions for usage outside these areas. The Organizations submit that any buffer corridor expanding these prohibitions outside these areas would be a violation of this specific management standard and The Organizations is not able to understand how designating a corridor in the Resource management plan would not be a violation of these standards as the conflict would directly involve the multiple uses in the RMP rather than being implemented in subsequent planning. Congress has prohibited exclusionary corridors at any time around an NTSA route.

The NTSA also provides guidance on the large-scale relocation of any Congressionally designated scenic trail from its original location as the NTSA continues as follows:

“Relocation of a segment of national, scenic or historic trail…. A substantial relocation of the rights of way for such a trail shall be by Act of Congress.” 15

While Congress was clear on the desire to retain authority over the alteration of any National Trail, the failure to define “significant” places any changes in a national scenic trail from its original location, in the case of the CDT the 1977 report to Congress outlining its location, on questionable legal basis.

In several locations in the NTSA, proper recognition of multiple usage of a National Trail is specifically and clearly identified in areas outside Wilderness, Parks and National Wildlife Refuges. The NTSA explicitly provides allowed usages as follows:

“j) TYPES OF TRAIL USE ALLOWED. Potential trail uses allowed on designated components of the national trails system may include, but are not limited to, the following: bicycling, cross-country skiing, day hiking, equestrian activities, jogging or similar fitness activities, trail biking, overnight and long-distance backpacking, snowmobiling, and surface water and underwater activities. Vehicles which may be permitted on certain trails may include, but need not be limited to, motorcycles, bicycles, four-wheel drive or all-terrain off-road vehicles. In addition, trail access for handicapped individuals may be provided. The provisions of this subsection shall not supersede any other provisions of this chapter or other Federal laws, or any State or local laws.”16

The Organizations would note that given the specific recognition of snowmobiling, four-wheel drive and all-terrain vehicles as allowed trail usages, any attempt to exclude such usages from the CDT would be on questionable legal ground. In addition to the above general provisions regarding multiple usage in areas around a National Scenic Trail, multiple usage of the Continental Divide Scenic Trail is also specifically and repeatedly addressed and protected in the NTSA. The CDT guidance starts as follows:

“Notwithstanding the provisions of section 1246(c) of this title, the use of motorized vehicles on roads which will be designated segments of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail shall be permitted in accordance with regulations prescribed by the appropriate Secretary.”17

The NTSA further addresses and protects multiple usage of the CDT is further addressed as follows:

“Where a national historic trail follows existing public roads, developed rights-of- way or waterways, and similar features of man’s non-historically related development, approximating the original location of a historic route, such segments may be marked to facilitate retracement of the historic route, and where a national historic trail parallels an existing public road, such road may be marked to commemorate the historic route. Other uses along the historic trails and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, which will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the trail, and which, at the time of designation, are allowed by administrative regulations, including the use of motorized vehicles, shall be permitted by the Secretary charged with the administration of the trail.“18

In addition to the specific provisions of the NTSA addressing the CDT, the CDT management plan further addresses multiple usage including the high levels of multiple use on the CDT in 2009. The CDT plans specifically states:

“(2) At the time the Study Report was completed (1976), it was estimated that approximately 424 miles (14 percent) of existing primitive roads would be included in the proposed CDNST alignment.”19

While the CDT plan does recognize levels of roads utilization, the CDT plan does not specifically address the miles of multiple use trail that are aligned along the CDT. Rather than providing specific analysis of this usage, the CDT plan provides that trails adopted through the travel management process are an allowed usage of the CDT, providing as follows:

“Motor vehicle use by the general public is prohibited on the CDNST, unless that use is consistent with the applicable land management plan and:

- Is necessary to meet emergencies;

- Is necessary to enable adjacent landowners or those with valid outstanding rights to have reasonable access to their lands or rights;

- Is for the purpose of allowing private landowners who have agreed to include their lands in the CDNST by cooperative agreement to use or cross those lands or adjacent lands from time to time in accordance with Federal regulations;

- Is on a motor vehicle route that crosses the CDNST, as long as that use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST;

- Is designated in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart B, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and:

- The vehicle class and width were allowed on that segment of the CDNST prior to November 10, 1978, and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST or

- That segment of the CDNST was constructed as a road prior to November 10, 1978; or

- In the case of over-snow vehicles, is allowed in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart C, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST.”20

The CDT plan further adopts multiple use principals by clearly adopting management standards for motorized categories of the recreational opportunity spectrum and as a result the concept of an exclusively non-motorized corridor would directly conflict with the CDT plan. While the NTSA fails to specifically address multiple use trails along the CTD, the Management Plan does specifically provide that multiple use routes adopted under relevant travel management decisions shall be allowed and consistent with applicable planning. At no point in the CDT plan is the concept of an exclusionary corridor even mentioned.

The Organizations submit that while specific portions of the NTSA are less than clear when read in isolation or in an attempt to apply Wilderness or National Park type restrictions outside these areas, the NTSA is very clear in conveying the position that the CTD is truly a multiple use trail and that the CTD should not serve as a barrier to multiple usage of adjacent areas. The Organizations submit that creation of a landscape level buffer around the CDT, where multiple usage was prohibited or restricted would be a violation of both the NTSA and the CDT management plan. This should be avoided as there are significant challenges on the Gila that are on a sounder legal basis and of significantly more important level to most forest users.

2d. NTSA management specifically requires a maximizing of economic benefits with is supplemented by relevant US Supreme Court rulings and Executive Orders mandate agencies balance management priorities based on the cost benefit analysis of the standard.

The implementation of a non-motorized Wilderness corridor around the CDT also gives rise to a wide range of issues when looked at from a cost-benefit perspective, which is made even more complex by the fact that the CDT runs through a wide range of lands, including public and private lands. The Organizations are also concerned that any heightening of the CDT management and a possible corridor around the trail as a management objective in the forest plan would be a difficult proposition when reviewed from a cost benefit analysis and against the maximization of multiple use benefits requirements of the NTSA.

The NTSA guidance is clear on issues involving equity and usage of NTSA routes and the need to balance multiple usage based on these factors based on economic returns associated with the management of the route. The NTSA explicitly provides as follows:

“(9) the relative uses of the lands involved, including: the number of anticipated visitor-days for the entire length of, as well as for segments of, such trail; the number of months which such trail, or segments thereof, will be open for recreation purposes; the economic and social benefits which might accrue from alternate land uses; and the estimated man-years of civilian employment and expenditures expected for the purposes of maintenance, supervision, and regulation of such trail;”21

While the Gila has significant challenges facing all usage of the forest by the public, such as poor forest health, impacts of drought conditions and expanding visitation to the Gila and continued strong demand for recreational opportunities, the CDT is a resource that is simply not used at a large enough scale by those seeking to exclude multiple uses to warrant directing extensive resources to revision of management efforts. A review of the Continental Divide Trail Coalition website reveals that approximately 2 dozen people traverse the entire CDT on an annual basis. 22 Unfortunately, this information is not broken down to more specific levels, such as usage of the CDT at state or forest levels. The Organizations can vigorously assert excluding multiple uses across a corridor for the benefit of as few as two dozen people is not maximizing economic and social benefits of these lands. Such as position simply lacks any factual basis.

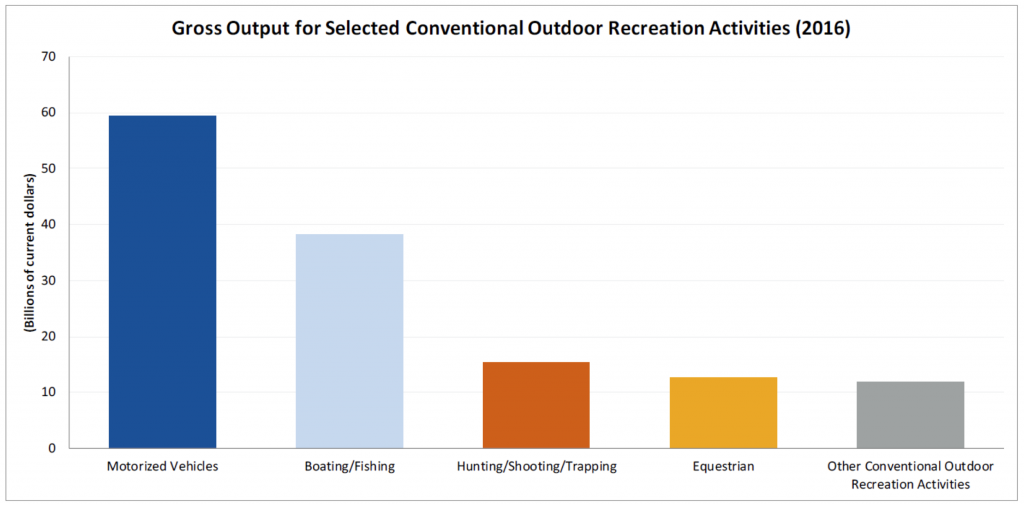

As land managers are specifically required to compare the economic benefits of alternative uses of the trail and any possible corridor under both multiple use principals of planning and as more specifically directed by the NTSA, accurate economic analysis information is critically important to the decision-making process. Additional new research regarding the economic importance of multiple use recreation to the recreational spending benefits flowing to local communities comes from research from the Department of Commerce, prepared at the request of Department of Interior Secretary Sally Jewel in 2012, addressing the importance of recreational spending in the Gross Domestic Product.23 This research also clearly identified the important role that motorized access plays in recreational spending, which is summarized in the following chart:

Given the fact that significant portions of the CDT are primarily used for recreational purposes, the comparative spending profiles of recreational usage is highly important information. It has been The Organizations’ experience that often comparative data across user groups is very difficult to obtain. The USFS provided such data as part of Round 2 of the National Visitor Use Monitoring process and those conclusions are as follows:

While the above agency summary data has become somewhat old, The Organizations simply don’t see any change in the comparative spending profiles of these user’s groups. The Organizations is aware of detailed research addressing certain portions of this analysis above. A copy of the most recent study of the Economic Contribution of the use of Off-Highway Vehicles in Colorado is attached to these comments. This analysis identifies a strong increase in the per person spending profiles of all user groups in the OHV/OSV community based on increased unit prices and new types of OHVs, such as side by side vehicles, being present in the marketplace.

The differences in comparative spending between the user groups allowed in a CDT corridor and those excluded from the corridor are stark and again simply do not favor designation of a landscape level corridor. When comparing the spending profiles of usages allowed in a proposed corridor such as hiking, primitive camping and cross-country skiing to the usages that are excluded from the corridor, such as OHV use and snowmobile the disparity of spending profiles is stark. The users excluded from a corridor spend anywhere from 1.5x to more than 2x the amount of the user groups that would be allowed in the corridor.

As a result of the stark differences in spending profiles of the users, visitation of those allowed in any corridor would have to essentially double throughout the year in order to offset lost economic benefits from the users that would be excluded. This position and expectation is factually unsupportable as visitation to certain portions of the CDT by permitted users is limited to as few as dozens of visitors per year, while visitation levels from users possibly excluded is significantly higher than the visitation levels that are allowed within a corridor. As a result, not only would corridor visitation have to double to offset lost users simply to break even on a per visitor days spending level but also the levels of visitation would have to massively expand as the levels of permitted corridor use is exceptionally low.

The Organizations do not contest that there are areas or attractions where the CDT sees very high levels of visitation but The Organizations is aware the areas of higher visitation are areas and issues that can be resolved at the site-specific level in an effective manner and should not be relied on for the basis of a forest wide corridor. Additionally, hikers of the trail are encouraged to visit local communities to the trail, which include Chama, Silver Springs and other communities. The Organizations is unsure how a Wilderness like corridor can be reconciled with developed resources such as these large communities. Any attempt to resolve these issues would be exceptionally expensive from a management perspective and would result in user conflict. The Organizations must question if these areas and CDT issues more generally could not be more effectively managed through site specific planning subsequent to the RMP finalization. The Organizations submit that there are numerous diverse challenges facing the CDT, many of which are highly site specific, which should be dealt with at the local level rather than trying to craft a landscape level fix to these issues. There are simply insufficient levels of utilization of the CDT at the landscape level to warrant inclusion of such issues in the RMP.

3. A Cost/Benefit analysis of corridor management must also be addressed.

In addition to having to balance economic interests in management of NTSA areas, both President Trump (EO 13771 in 2017) and President Obama (EO 13563 in 2011) have issued Executive Orders requiring all federal agencies to undertake a cost benefit analysis of management decisions. The US Supreme Court recently specifically addressed the need for cost benefit analysis as an issue and stated as follows:

“And it is particularly so in an age of limited resources available to deal with grave environmental problems, where too much wasteful expenditure devoted to one problem may well mean considerably fewer resources available to deal effectively with other (perhaps more serious) problems.”25

Given this clear statement of concern over the wasteful expenditure of resources for certain activities or management decisions, The Organizations are very concerned regarding what could easily be the wasteful expenditure of resources for the benefit of what is a very small portion of the recreational community.

The Organizations submit that there can be no factually based arguments made that closures of large areas of the Galan to historical travel will not result in significant massive additional costs to land managers that really cannot be justified given the huge challenges managers are facing such as poor forest health and large increases in wildfire severity and frequency. Simply educating the public regarding the new closure would be exceptionally costly as new signage and other educational materials would have to be developed and then signage would have to be maintained. This would have to include signage that probably makes little sense on the ground as natural landmarks are not relied on for boundaries, and these signs would have to be placed in areas where they could be found and also maintained to insure signage is not buried in snow.

The Organizations submit that proper balancing of enforcement costs with the benefit to small user group is exactly the type balance that the Supreme Court and both President Obama and President Trump has expected the agencies to undertake as part of any planning process. The Organizations submit that a non-motorized corridor around the CDT fails from a cost benefit perspective even if Congressional action and relevant plans allowed such as management decision.

4. Conclusion.

The Organizations are aware that often the lack of basic access to public lands due to management restrictions is a major management challenge when addressing large scale issues, such as poor forest health or drought. Providing a balanced management goal and objective for the Forest would allow for future managers to address challenges from population growth and meaningfully address challenges to the Forest that simply might not even be thought of at this time. Why are The Organizations concerned? Too often recreational access to public lands is lost when maintenance cannot be performed in a cost-effective manner. Adding additional management standards that will at a minimum need an additional round of NEPA planning to address future management challenges simply makes no sense.

The Organizations are very concerned that as exclusionary corridors around the CDT and other National Trail System Act routes have moved forward in resource planning, often these corridors immediately become non-motorized corridors without addressing existing usages of these corridor areas as exemplified by the multiple forests in California moving forward with winter travel planning and the adoption of the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan in Southern California by the BLM and numerous forests in the Rocky Mountains. While corridors are immediately to be applied in the preferred alternative, at no point is there any analysis of possible impacts to existing usages is even mentioned despite numerous requirements in federal law requiring a specific review of these types of impacts.

The Organizations are pleased to have been provided this opportunity to provide input on the Gila NF planning process and looks forward to working to resolve any issues as the plan moves forward. Please feel free to contact either Don Riggle at 719-338-4106 or by mail at 725 Palomar Lane, Colorado Springs CO 80906 or Scott Jones, Esq at 518-281-5810 or by mail at 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont, CO 80504 for copies of any documentation that is relied on in this appeal or if you should wish to discuss any of the concerns raised further.

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

TPA/ORBA Authorized Representative

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

Fred Wiley

CNSA Past President ORBA President

CEO One Voice Authorized Representative

- See, USDA Forest Service; Preliminary Draft Land Management Plan for the Gila NF; March 2018 at pg. 179. Hereinafter referred to as “the Proposal”.

- See, 16 USC 2146 (j).

- See, USDA Forest Service and New Mexico State Forest Service; New Mexico Forest Health Conditions; 2017 at pg. 1.

- See, Proposal at pg. 176.

- See, Proposal at pg. 176.

- See, Proposal at pg. 177.

- See, Proposal at pgs. 177-178.

- See, 2016 USFS CDT Guidance at Pg. 9 – Senate Report No 95-636, 1978 is not available to the public- when searched on the Congressional history the following report is provided: “As of 12/15/2017 the text of this report has not been received.”

- See, HRep 1631 at pg. 3873.

- See, HRep 1631 at pg. 3861.

- See, HRep 1631 at pg. 3859.

- See, HR 1631 at pg. 3873.

- See, 2016 USFS CDT Guidance at pg. 1.

- See, 16 USC 1246(a)(2) emphasis added.

- See, 16 USC 1246(b)(ii).

- See, 16 USC 1246(j).

- See, 16 USC 1244(a)(5)

- See, 16 USC 1246(C) emphasis added.

- See, USDA Forest Service; The 2009 Continental Divide National Scenic Trail Comprehensive Plan; September 2009 at pg. 19.

- See, USFS: The Continental Divide Scenic Trail Comprehensive Plan; 2009 at pg. 19.

- See, 16 USC §1244(b)(9)

- See, http://continentaldividetrail.org/cdtc-official-list-of-cdt-thru-hikers/

- See, Department of Commerce; Bureau of Economic Analysis; “Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account: Prototype Statistics for 2012-2016”; February 14, 2018 at pg. 2.

- See, USDA Forest Service; White and Stynes; Updated Spending Profiles for National Forest Recreation Visitors by Activity; September 2010 at pg. 6.

- See, Entergy Corp v. Riverkeeper Inc et al; 556 US; 475 F3d 83; (2009) Opinion of Breyer J, at pg. 4