GMUG National Forest

Att: Forest Plan revision

2250 South Main Street,

Delta, CO 81416

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the comments of the above Organizations with regard to the pre-NEPA release of the draft GMUG Resource Plan (“hereinafter referred to as “the Proposal”). The Organizations welcome the opportunity to provide our input prior to the commencement of the formal NEPA process governing development of the RMP. Our preliminary thoughts for the Proposal would include:

- We welcome the brief nature of the RMP and the opportunity to comment on the Proposal prior to the commencement of the formal NEPA process;

- Presentations to the public in this pre-review have sometimes conflicted with the RMP provisions;

- Better maps for the Proposal are needed;

- Revisions of existing travel management decisions should occur on a more localized level than a forest plan;

- There needs to be flexibility in the ROS management standards for non-motorized areas;

- The Winter ROS recommendations needs extensive review and amendments due to closure of most of the southern portion of the forest to OSV usage;

- Lynx habitat needs to be managed in accordance with the 2013 LCAS;

- Continental Divide Trail management must comply with National Trails System Act mandates and the Continental Divide Trail Plan;

- The Organizations are unsure what benefit is sought to be achieved by placing seasonal closure dates for a limited number of species in the RMP; and

- The Organizations remain opposed to the sham public process of the GPLI and any recommendations from this process as any assertion of public process is a direct violation of the Colorado Sunshine Act for committees convened by a County.

Prior to addressing the specific thoughts on the Proposal, our Organizations have regarding the pre-NEPA review of the GMUG RMP, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all of the more than 200,000 OHV recreationists in Colorado in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite the more than 30,000 winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport.

1. Pre-NEPA public review.

The Organizations first must vigorously thank the GMUG planners for the opportunity to review and comment on the draft RMP before the commencement of the formal NEPA process. While this step is unusual, and frankly took us by surprise in the beginning, we now understand the intent of the informal comment period and would encourage other forests to adopt this additional step prior to formally starting the NEPA process. We believe this step will avoid unnecessary conflict during the more formal NEPA process. The Organizations have participated in too many planning processes where there is unnecessary conflict that results from inadvertent oversights in the planning efforts, such as map development, once the NEPA timeline has been started. These minor oversights can damage partnerships that have taken years to develop and should be avoided at all costs.

The Organizations also believe this additional step sends a significant message to the public mainly that developing a quality resource management plan for the GMUG is a higher priority than developing a fast RMP for the GMUG. It has been our experience that too often planning process strive to be fast rather than developing a high-quality long-term vision for the planning area. As a result, we are aware of several plans, that while quickly developed, are now suffering from foundational issues that are seriously hampering the implementation of any changes in the planning area. The development of a high-quality plan for the GMUG has to remain the goal of the planning efforts as a quality plan will have a longer relevant life span for the forest. A quality plan will be more cost effective for the forest as there will be a more streamlined site-specific planning process as site specific planning can implement a high-quality land scape decision rather than fix a lower quality landscape plan and then proceed with local planning.

We are also aware that several of the issues we are going to raise in these comments are not simple to unwind out of the plan. This effort is going to take time and we believe this time is now more available as the NEPA process has not been started. That again contributes to a quality forest plan.

2. Shorter is better.

The Organizations welcome the generalized and shorter nature of the RMP when compared to the former GMUG plan and Uncompahgre BLM Field Office. The UFO proposal encompasses more than 1000 pages of plan and analysis and provides extensive detail on every issue imaginable. While the Organizations understand the desire to insert numerous small plans into a larger planning process, it has been the Organizations experience that merely combining numerous small plans into a single large plan results in poor analysis of issues facing these projects, poor coordination of planning efforts and an exceptionally complex plan that results in large barriers when landscape level plans issues are addressed. Often some of the complexity is the result of a desire to combine numerous small issues into the RMP in the belief that the RMP will expedite these projects. This should be avoided as we are aware of a very limited number of site-specific projects that have been completed as the result of their inclusion in landscape level plans. Almost every one of the projects has required extensive site-specific analysis to complete and rarely has the landscape plan streamlined subsequent site-specific plans to levels that would justify the landscape level efforts.

The consolidation of multiple site-specific plans also yields a landscape plan that is VERY long and detailed. This length has proven to be a significant barrier to public participation in the planning process as most of the public lack the time or resources to review such a large planning document. This causes the public to oppose the plan even when there are very good things for the public in the plan. These overly complex and detailed plans also shorten the life and value of the plan as the plan simply lacks flexibility to adapt to changes in science or unforeseen challenges at the time of development. When these changes are encountered, the plan is simply irrelevant factually or recommending management that simply makes no sense in addressing on the ground issues. The current forest health situation on the GMUG provides a perfect example of why RMPs must be flexible and avoid overly detailed analysis, mainly that the GMUG is dealing with areas of the forest where tree mortality is easily at or above 90%. The Organizations submit that the current RMP has been a significant barrier to addressing this challenge, as planners in 1983 were simply unable to understand the scope of the challenges that the forest could be facing almost 40 years after the plan was adopted. Again, these types of overdetailed analysis represent a situation that should be avoided in the development of the new GMUG RMP. Shorter is better.

3a. Better detail in all maps is needed.

The Organizations first substantive concern about the Proposal is that the maps provided with the Proposal simply need greater detail in terms of landmarks and topography in order to allow for meaningful public comment. The lack of significant landmarks and topography makes identification of landmarks difficult at best. This simply must be remedied. The Organizations are aware that many planning efforts have moved to an entirely on-line interactive mapping process, which is welcomed in dealing with local issues or concerns but the detail that is so valuable in local discussions often becomes overwhelming at the landscape level. Too often our members spend more time trying to locate landscapes with the interactive mapping and become lost in the on-line map. We are asking that both the .pdf and interactive mapping tools be available to the public in the planning process and that each tool provide similar information.

In addition to the lack of landmarks, there appears to be significantly less detail in the maps that are provided in .pdf format than those that are available in the on-line interactive mapping tools. This is exemplified by the fact that zooming the interactive mapping tool provides detail down to specific trails and roads approved in travel management, while zooming the .pdf map fails to add any detail to the map. We are unsure why there would be a difference in the amount of detail available between the two platforms, but each platform should be providing similar levels of detail for the planning process. While we appreciate the detail and lay of the land navigation that can be achieved with the more detailed interactive mapping this detail is not suited to all applications and uses. The .pdf maps can be cut and pasted into comments by the public, which expands their value beyond simply quickly reviewing the forest at the landscape level as specific geographic areas of concern can be quickly and easily identified.

The Organizations believe that the White River National Forests .pdf maps released as part of their forest level travel plans were of reasonable quality and detail to facilitate discussions and this value is improved by the addition of the on-line interactive mapping resources that are now available. The Organizations would ask that .pdf maps of similar quality be provided in addition to the interactive online mapping resources that are available.

3b. Presentation materials for public discussion must match the RMP standards.

The Organizations participated in several of the public meetings around the pre-NEPA release of the GMUG plan and found that on several issues the presentation materials for the public discussion did not match the standards for that issue provided in the RMP. The Organizations are aware that the pre-NEPA public review of the GMUG plan is unusual at best and we have to believe that this is contributed to possible conflicts between public materials and the RMP and that these issues would be resolved prior to the NEPA process commencing.

While we understand the unusual course the RMP has taken, this issue is of sufficient concern to be raised as these types of conflict can rapidly erode public support for a plan that could be widely supported by the public. The Organizations believe this is a simple issue that could be remedied with a more traditional plan development roadmap and is something that could be resolved with some additional time for planners to polish materials. While we are comfortable in the fact that this issue will be resolved, we also believe the issue is of enough significance to warrant a statement of concern regarding.

4. Travel management should occur on a more localized level than the forest level.

The Organizations are aware that a certain amount of travel management will occur in the forest level resource planning and that this is unavoidable. The Organizations are also aware that nationally the BLM has moved away from preparing Field Office level travel plans and in favor of preparing any travel management plan on a more localized level as a matter of policy. This decision applies to all Field Offices regardless of where they are in the travel planning process, which is interesting as we are aware of numerous Field Offices which are adopting this policy in their first round of travel management. The BLM White River FO has adopted this level of planning and this has proven to be HIGHLY effective in developing high quality recreational opportunities on the ground and avoids the situation where areas are overlooked or routes are simply dropped from review due to the fact they were omitted or overlooked from the mapping process. This local level planning has occurred despite the fact that the White River FO is moving forward with its initial travel planning for the FO.

Moving travel management to a more localized level also allows for far more detailed public input and discussion in the travel process, which results in better long-term support for any result of the planning process. This public support is a good thing and should be a higher priority as the GMUG has completed its first round of travel planning, and the Organizations believe that since the GMUG has already completed a first round of travel planning, more localized planning should be a more achievable goal due to the fact basic resource protection has already been addressed on the GMUG. Many times the public participants in the local travel efforts are also the strongest partners with the USFS after completion of the travel planning process at the more local level.

While we are unsure if this type of management process is even available in the USFS or if the GMUG could move to this type of travel management process at this point in their planning process the Organizations would vigorously support moving to this level of travel management. Moving travel management planning to at least a Ranger District level would allow managers to more effectively address issues as certain Ranger Districts, which might have more travel management issues compared to others could proceed with district level travel planning while other offices could proceed at a later time when travel might be a larger issue. This would be both cost effective and result in higher quality plans, and both of these are good things.

5. The proposed Designated Trails standard should simply be removed as it is arbitrary and yields unclear benefits.

The Organizations have participated in the development of literally dozens of resource management plans throughout the western united states and we are simply unable to identify another plan that provides a calculation of the designated trails foot print on the Forest. Not only is the proposed standard unclear regarding application moving forward, the proposal arbitrarily limits the scope of what is a designated route for reasons that remain unclear. The Organizations any attempt to justify this standard would be opening pandora’s box seeking to obtain benefits that at best remain unclear. This standard should simply be removed.

Under the GMUG draft RMP designated trails are provided for as follows:

Designated Trails (DTRL)

Designated trails include national scenic, historic, and recreation trails. In the Working Draft Forest Plan, Designated Trails encompass a mapped area of approximately 77,600 acres (2.5% of the Forests) that overlays multiple other Management Areas. 1

Candidly, the Organization simply have no idea what this provision means or how this provision was developed or what the long term impacts from such a designation could be. The provisions don’t seem to be a desired condition, standard, guideline or in any way fit with the rest of the management planning efforts. Without further information being available we are not able to provide more substantive analysis of the designated trail issue as the Organizations are simply unable to understand the management concern that is being raised or how particular standards or levels were developed. The Organizations are simply unable to understand how 2.5% of the forest was identified or the ramifications to future management.

The Organizations would note that this calculation would be highly suspect if the management standards for the Continental Divide trail were implemented. Clearly implementing a .5-mile- wide corridor around the CDT would impact more than 2.5% of the forest as routes would end up being severed in the planning process and result in numerous dead-end routes of limited value.

Additionally, the Organizations have to express serious concern about how the definition of “Designated Trails” was limited to merely NTSA routes given that the motorized community has been subject to the travel management orders since 1972. Pursuant to Executive Order 11644 land mangers are mandated to designate areas of public land where motorized usage is open, closed and restricted to designated routes based on a variety of resource and recreational concerns. The Organizations assert that the Executive Branch planning requirements for designation are equally enforceable to a Congressional designation and any attempt to separate these two designation processes would immediately lack factual or legal basis.

The Organizations submit that given the questionable need for such a Designated Trails standard moving forward and horribly arbitrary nature of the current standard that is proposed for designation, that such a standard should simply be removed. We are unsure of any benefits and believe that the process to attempt to explain and understand the benefits of a Designated Trails standard would be a significant undertaking. There are simply higher priorities for the GMUG moving forward than opening pandora’s box on this issue.

6(a)(1). CDT management standards are internally conflicting and must be reviewed.

Prior to addressing the Organizations concerns around management of the Continental Divide Trail (“CDT”) and adjacent areas, this is an issue where the public presentation materials and the Proposal are directly conflicting. The Organizations deeply hope that the Proposal is amended to reflect the repeated assertions in the initial public meetings from USFS staff that the CDT will be managed for multiple usage in accordance with the CDT plan and National Trail System Act (“NTSA”) requirements. The Organizations vigorously assert federal law must be complied with in the management of the CDT, and at no point does federal law support most of the Proposed management of the CDT in the Proposal. The Organizations are also not aware of any issues with the management of the CDT, and as a result must question why managers would seek to create conflict over management of an issue that is largely resolved right now. Right now the motorized and non-motorized community effectively pool very limited resources to work towards the maintenance of the CDT for all users, and this type of collaboration would be unnecessarily challenged with implementation of the proposed standards.

In addition to avoiding conflict with Federal law, the Organizations have been actively participating in the winter travel planning efforts on the Tahoe NF, Stanislaus NF, Lassen NF, Eldorado NF and Plumas NF in California. The reason this is being mentioned is that the implementation of management standards exceptionally similar to the proposed GMUG provisions for the CDT have been explored in the travel management on these forests for the Pacific Crest Trail. The exploration of these standards in the large open riding areas that are the most sought after by the winter motorized community has triggered some of the ugliest and most contentious fights between users we have seen in a long time. Generally, land managers are moving towards resolving these conflicts by returning management of the PCT to a manner identical to current management.

The scale of the impact of proposed changes is clearly identified in the 1983 GMUG RMP, which clearly states as follows:

“One hundred and thirty miles of this trail corridor are on the Gunnison National Forest. Of the 130 miles, 83 or 64% cross land which offers primitive or semi-primitive non- motorized recreation opportunities. Nineteen miles or 14% cross land which offers semi- primitive motorized recreation opportunities, and 28 miles or 22% cross land which offers roaded natural recreation opportunities.” 2

The existing RMP specifically allows motorized usage of the CDT footprint and we would be opposed to any changes in such a standard. Clearly the Organizations are vigorously opposed to any attempt to close more than 47 miles of roads and trails to implement an interpretation of the NTSA that is erroneous. It should also be noted that the corridor concept discussed generally in the 1983 GMUG RMP was removed from the NTSA by Congress in 1983.

In our opinion this fight is completely unnecessary as the NTSA is very clear in its identification that any NTSA route is multiple use at the landscape level, both by specifically stating this and clearly identifying the wide range of usages that are permitted and there is simply no conflict we are aware around multiple uses of the CDT on the GMUG. This partnership is exemplified by the fact that CSA in partnership with local clubs and numerous clubs groom significant portions of the CDT for winter recreation and this in no way relates to hiking or horseback riding. This type of partnership would be immediately put at risk if the new management standards were implemented under the RMP and this type of risk is simply unacceptable to the Organizations.

The proposed CDT provisions of the GMUG draft are directly in conflict with NTSA statutory provisions and the CDT plan in numerous locations and at often times directly conflict with provisions for the management of the CDT provide within the RMP. At best many of these provisions draw any multiple use of existing CDT areas into question. The provisions that most directly in conflict with NTSA requirements in the GMUG plan are as follows:

Desired Conditions

FW-DC-DTRL-01: The Continental Divide National Scenic Trail is a well-defined trail that provides for high-quality hiking and horseback riding opportunities, and other compatible non-motorized trail activities, in a naturally-appearing setting along the Continental Divide. Where possible, the trail provides visitors with expansive views of the natural landscapes along the Continental Divide. See also Scenery FW- GDL-SCNY-03. 3

Guidelines

FW-STND-DTRL-06: Existing motorized use may continue on the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, as long as it does not substantially interfere with the trail’s nature and purpose. 4

FW-GDL-DTRL-10: To promote high-quality scenic, primitive hiking and horseback riding opportunities along the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, the minimum trail facilities necessary to safely accommodate the amount and types of use anticipated on any given trail segment should be provided. 5

FW-GDL-DTRL-17: To promote a naturally appearing, non-motorized setting on the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, constructing permanent roads or motorized trails across or adjacent to the trail should be avoided. 6

Before addressing the legal concerns for the above CDT management provisions, the Organizations must clearly state that we are entirely unable to even reconcile the above standards with each other. The Organizations are simply unable to reconcile the statement that the only allowed usages are non-motorized and motorized usage is allowed to continue if it does not interfere with the desired conditions. FW-STND-DTRL-06 simply cannot be reconciled with FW-GDL-DTRL-17 which does not allow motorized roads and trails within an unspecified distance of the CDT. The fact that there is no attempt to even quantify what the term adjacent to the trail even means. Does “adjacent to the trail” mean 100 ft, .5 miles, somehow related to topography? We are unsure and it is these types of basic questions in applying the proposed standards on the ground. This type of management simply fails to provide the detailed statement of high-quality information for a management decision that is required by NEPA.

6(a)(2). GMUG CDT management conflicts with management of the CDT on adjacent units

The Organizations recently conducted a trail training in partnership with the Salida Ranger District and one of the breakout discussions at this event was the management of the Monarch Crest Trail on the Salida Ranger District. On many portions of the CDT, the trail footprint is collocated with numerous other resources such as the Monarch Crest Trail, Colorado Trail and Marshal Pass Road. This discussion is highly relevant as the Salida Ranger District of the PSI and districts on the GMUG directly about each other for long distances over highly visited terrain by all recreational users.

As part of the presentation, we discussed the huge success of the new trail signage around the multiple use nature of the Monarch Crest Trail that was developed with the Central Colorado Mountain Trail Riders for the Monarch Crest Trail, which is exemplified as follows:

The lack of factual basis for any assertion that the Monarch Crest/CDT must be managed only to provide hiking and horseback opportunities is immediately clear when compared to this signage which was consistently identified as hugely effective and many land managers sought to have expanded on to their districts as the signage specifically identifies the CDT trail on the bottom of the sign. It should be noted that the San Isabel NF is clearly identified at the bottom of these signs.

Any assertion that one Ranger District could interpret the NTSA such completely opposing legal manners is simply without basis. Even the basic assertion of such authority would directly undermine the partnerships that have been developed between users and land managers and again points to the folly of any assertion that the CDT is to be managed for only hiking and horseback usage as the CDT and Monarch Crest Trail are one in the same for long distances in Colorado.

6b. CDT management must be aligned with National Trail System Act requirements.

Prior to moving forward into discussion of the apparently conflicting provisions of the NTSA and Proposal regarding usage, the Organizations believe a review of one of the foundational canons of statutory interpretation is needed as the Proposal management is directly governed by the National Trails System Act. In 1850, the US Supreme Court stated the following foundational concept of statutory interpretation as follows:

“In expounding a statute, we must not be guided by a single sentence or member of a sentence, but look to the provisions of the whole law, and to its object and policy.” 7

The US Supreme Court recently reaffirmed this basic tenant of statutory construction as follows:

“Statutory construction … is a holistic endeavor. A provision that may seem ambiguous in isolation is often clarified by the remainder of the statutory scheme—because the same terminology is used elsewhere in a context that makes its meaning clear, or because only one of the permissible meanings produces a substantive effect that is compatible with the rest of the law.” 8

The Organizations urge the USFS to look at the entirety of the NTSA, recognize the application of the multiple use mandates in the provisions governing these routes, and develop management provisions that reflect the entirety of the NTSA standards rather than seeking to apply one small portion of one provision of the NTSA in a manner that would render the rest of the NTSA irrelevant. This interpretation is a direct violation of the NTSA and basic canons of statutory interpretation that have been applied consistently for hundreds of years by US Courts.

Throughout the CDT portions of the Proposal, there consistently are assertions that are made to the effect that the CDT is managed for hiking and horseback only, as exemplified by desired condition FW-DC-DTRL-01. The Organizations are simply unable to find any legal basis for these assertions in the NTSA, as the NTSA specifically states the scope of usage of any NTSA route as follows:

“j)TYPES OF TRAIL USE ALLOWED. Potential trail uses allowed on designated components of the national trails system may include, but are not limited to, the following: bicycling, cross-country skiing, day hiking, equestrian activities, jogging or similar fitness activities, trail biking, overnight and long-distance backpacking, snowmobiling, and surface water and underwater activities. Vehicles which may be permitted on certain trails may include, but need not be limited to, motorcycles, bicycles, four-wheel drive or all-terrain off-road

vehicles. In addition, trail access for handicapped individuals may be provided. The provisions of this subsection shall not supersede any other provisions of this chapter or other Federal laws, or any State or local laws.” 9

The Organizations must briefly address the management history of the CDT, as the Organizations submit these principals are highly relevant to any assertion of allowing only non-motorized uses on any NTSA route and clearly reflects the fact that Congress specifically stated multiple use goals and objectives for the trail rather than merely stating multiple use requirements govern these trails. Management of the CDT is generally governed by the 1983 NTSA amendments which specifically addresses multiple usage concepts for areas adjacent to trails and how these multiple use mandates will relate to management of the Trail. The NTSA subsequent to the 1983 amendments provides in 16 USC §1246(A) as follows:

“in selecting the rights-of-way full consideration shall be given to minimizing the adverse effects upon the adjacent landowner or user and his operation. Development and management of each segment of the National Trails System shall be designed to harmonize with and complement any established multiple use plans for that specific area in order to insure continued maximum benefits from the land.” 10

The provisions Congress inserted with the 1983 amendments to the NTSA are exceptionally clear and prohibit the concept of a corridor/crossing point around the CDT and remain in place as controlling federal law to this day. In several locations in the NTSA, proper recognition of multiple usage characteristics of any National Trail is specifically and clearly identified and motorized usages of the trail corridor/crossing point were clearly identified as acceptable.

The Organizations would also note that the travel management process with the standards of Open, Closed or Restricted motor vehicle usage has always been managed under multiple use planning requirements. Any assertion of the need for a corridor would create a 4th category of land management designation under the travel rule. As this classification has NOT been provided for in the most recent travel rule or related Executive Orders, the Organizations submit there is simply no provision for management as proposed under the travel management rule.

It is significant to note that the 16 USC 1246(j) remains in this form and controlling federal law on usage of NTSA routes to this day and that any time Congress has taken action Congressional actions have consistently identified the desire to provide a multiple use experience on any route that is designated under the National Trails System Act. The Organizations believe it is repetitive at best to point out the conflict between managing the entire CDT on the GMUG with NTSA provisions that specifically allow motorized usages on portions of the trail.

Even prior to the amendment of the NTSA in 1983, the desire of Congress to improve recreation in all forms was clearly identified. Multiple uses of corridor/crossing points and trails was originally addressed in House Report 1631 (“HRep 1631”) issued in conjunction with the passage of the NTSA in 1968. HRep 1631 provides detailed guidance regarding the intent of the Legislation, and options that Congress declined to implement in the Legislation when it was passed. HRep 1631 provides a clear statement of the intent of Congress regarding multiple usages with passage of NTSA, which is as follows:

“The aim of recreation trails is to satisfy a variety of recreation interests primarily at locations readily accessible to the population centers of the Nation.” 11

The Organizations note that satisfaction of a variety of recreation interests on public lands simply is not achieved with the implementation of any width corridor/crossing point around a usage or trail and relying on crossing points. Rather than providing satisfaction for all uses, implementation of mandatory corridor/crossing points in open OSV areas will result in unprecedented conflict between users and directly conflicts with the intent of Congress at the time the NTSA was passed. This intent has repeatedly been clarified with amendments to the NTSA since. HRep 1631 clearly and unequivocally states Congress declined to apply mandatory management corridor/crossing points of any width in the 1968 version of Legislation.

6c. Proposed CDT management on the GMUG conflict with the CDT plan.

As the Organizations have previously noted, the NTSA falls well short of restricting NTSA route usage to only horses and hiking usages as this legislation clears states the multiple use nature of any NTSA route as a whole. It is significant to note that Continental Divide Trail plan (“CDT Plan”) has adopted a blanket recognition of relevant travel management of areas around the CDT in its management plan. The 2009 CDT Plan provisions are as follows:

“Motor vehicle use by the general public is prohibited on the CDNST, unless that use is consistent with the applicable land management plan and……. (5) Is designated in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart B, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and:

(a)The vehicle class and width were allowed on that segment of the CDNST prior to November 10, 1978, and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST or

(b)That segment of the CDNST was constructed as a road prior to November 10, 1978; or

(6) In the case of over-snow vehicles, is allowed in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart C, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST.” 12

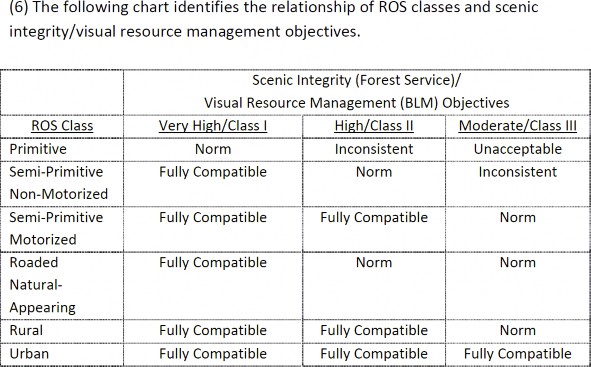

The Organizations must clearly and vigorously state that any proposed exclusionary corridor/crossing point around the CDT on the GMUG for the benefit of one user group over others, in name or function, would be a direct violation of the NTSA provisions mandating management of the trail area be in harmony with adjacent multiple uses of federal lands. The conflict with the CDT plan and basic assumptions in the Proposal is further evidenced by the fact the CDT plan specially identifies how ROS management should relate to CDT management providing as follows:

The Organizations are simply unable to understand why the chart above would not be cut and pasted in the Proposal for management of the CDT. In addition to the above ROS chart, the CDT plan provides great detail regarding the relationship of various uses to each other and the expertly level of interaction between uses across the ROS spectrum. Again, the Organizations are unable to understand why CDT management would be addressed in any other way than simply stating the CDT will be managed in accordance with the CDT plan.

The Organizations vigorously assert that all NTSA/CDT route management standards must be amended to avoid both internal conflict in the Plan but also to create consistency with both the NTSA and CDT management plans.

7. Additional flexibility must be provided in ROS standards.

The Organizations are expecting the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (“ROS”) to play a much larger role in shaping the forest under the new planning rule than it has in previous planning efforts. We support the application of the ROS in this manner, when the terms of the ROS are properly defined and allows for a certain degree of flexibility in its application. Unfortunately, the ROS definitions in the GMUG are exceptionally rigid and would result in the unnecessary loss of routes simply due to inventory issues and could become an even more significant barrier over the life of the RMP as some level of flexibility would be necessary to address issues like reroutes of existing routes on boundary areas, expansion of trailhead facilities for all usages and the ability of land managers to address landscape level changes on the forest, such as the extensive damage to routes that resulted from avalanche activity this year. Rather than allowing flexibility for managers to address issues like the Ophir boundary issue identified for winter travel, these ROS proposals are more inflexible than current management. This simply must be avoided and managers must have some flexibility with these landscape level standards or there simply may not be a route to fix or a use to address and rebalance after an intervening act. This situation simply must be avoided.

Why is there a need for flexibility in the ROS? It has been our experience in working with land managers over the years in developing close to a dozen resource management plans that even the best inventory of routes misses some routes, and it has been our experience that sometimes the routes are very important to access resources recently constructed with partners. This would be exemplified by the failure to include the general access route to the Bangs Canyon SRMA on the Grand Junction Field Office, which had just completed a major overhaul that was hailed as a success by everyone involved. This issue was caught at the last second of the inventory and quickly added but this route would have been lost if the current ROS was applied. It just happens regardless of the quality and vigor of the inventory, and the Organizations would like to avoid the loss of any routes due to inadvertent errors in the inventory.

The overly strict ROS definition could also serve as a major barrier to the expanded access to usages that are otherwise consistent with the ROS goals, and this issue could become a major concern towards the end of the life of the plan. Without basic flexibility in the ROS, projects such as adding parking lots for Wilderness access, trailhead access improvements and other recreational improvements would be more difficult if not impossible to do due to the conflict with the RMP. We don’t believe this is the intent of the ROS.

Currently the ROS standards are exceptionally rigid especially for non-motorized areas as the definitions are provided in absolute terms, which is obvious when compared between motorized and non-motorized usages. The current ROS provisions provide as follows:

Semi- primitive non-motorized

These settings are free of motorized recreation transport, but the use of mechanized transport may occur. 14

Semi primitive motorized

During the winter, routes are either ungroomed or groomed and are often signed and marked. Vast areas to travel cross-country in designated areas are available during certain winter months, offering visitors an opportunity for exploration and challenge. 15

ROS is a landscape tool but the standards in GMUG completely lack flexibility for subsequent site- specific planning. The Organizations would ask that some level of flexibility be incorporated in the non-motorized ROS and would recommend the following changes reflected in italics:

“These settings are generally free of motorized recreation or transport, but the use of mechanized transport may occur. If encountered motorized usages would generally be of a low intensity type nature.”

The Organization submit that such an amendment would retain the desired experience in these non-motorized areas but also allow the flexibility to allow managers to address inventory issues, the desire to improve access to recreational opportunities in these areas, streamline maintenance costs and simply build in some level of flexibility in the RMP to allow future land managers to address issues that simply cannot be foreseen at this time.

8. GMUG lynx management appears to conflict with best available science on numerous basic

The Organizations were surprised and disappointed at the lynx management standards in the Proposal. Rather than being an accurate reflection of best available science that has been clearly provided through collaborative efforts between the USFS, USFWS, BLM and NPS, the GMUG standards have to be one of the more restrictive summaries of numerous documents that have been superseded as a matter of law. This is a usual starting point for the development of an RMP that may be governing the forest for more than the next 30 years and clearly will draw these planning provisions into immediate conflict with best available science. Adopting standards that are already superseded in this situation simply makes no sense and many of the basic management standards for the lynx are foundational in nature, such as managing for two levels of habitat per best available science while the GMUG proposes to manage all habitat as the same issue, and must be corrected.

The disappointment of the Organizations is driven not only by this situation but also the fact the Organizations were active participants with the several other groups in what became known as the Colorado lynx blueprint project, which resulted in the 2013 LCAS. In addition to years of meetings and significant resources from numerous partners, the Organizations attempted to donate a snowmobile to researchers and supported researchers over years of efforts including recovering stuck equipment in the backcountry with snowmobile grooming equipment, providing parts, oil and fuel for efforts on an as needed basis and printing and circulating a copy of the LCAS to every Ranger District and Field Office in the state. As a result of these efforts, the Organizations have some significant vested interests in the success of the management of the species. These are also the types of partnerships the USFS is seeking to develop long term and failing to implement standards developed by these partnerships and approved by the USFS simply sends the wrong message on the value of partnerships.

Prior to addressing our specific concerns on management standards for the species, the Organizations would like to dispel any thoughts that previous management documents might still be applicable on forest service lands. The 2013 LCAS clearly states the document is the standard to be applied for federal lands management efforts moving forward including the §17 Consultation process, stating as follows:

“The Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy (LCAS) was developed to provide a consistent and effective approach to conserve Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis), hereafter referred to as lynx, and to assist with Section 7 consultation under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) on federal lands in the contiguous United States…. The Steering Committee selected a Science Team, led by Dr. Leonard Ruggiero, FS- Rocky Mountain Re-search Station, to assemble the best available scientific information on lynx, and appointed a Lynx Biology Team, led by Bill Ruediger, FS- Northern Region, to prepare a lynx conservation strategy applicable to federal land management in the contiguous United States.” 16

The 2013 LCAS clearly states its applicability to all planning in the future as follows:

“This edition of the LCAS provides a full revision, incorporating all prior amendments and clarifications, substantial new scientific information that has emerged since 2000 including related parts of the Lynx Recovery Plan Outline, as well as drawing on experience gained in implementing the 2000 LCAS. The document has been reorganized and condensed to improve readability and reduce redundancy.” 17

The 2013 LCAS further states the reasoning for moving from standards and guidelines for management of the Lynx in conservation measures is as follows:

“Guidance provided in the revised LCAS is no longer written in the framework of objectives, standards, and guide-lines as used in land management planning, but rather as conservation measures. This change was made to more clearly distinguish between the management direction that has been established through the public planning and decision-making process, versus conservation measures that are meant to synthesize and interpret evolving scientific information.”

When the specific standards of the 2013 LCAS are compared to the management standards and goals in the GMUG draft, the direct conflict with the 2013 LCAS is immediately apparent. This conflict starts immediately with the fact that the 2008 Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment is identified as controlling the development of the RMP as follows:

“Standards

FW-STND-SPEC-51: The Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment direction (Appendix 2), as amended and modified by the GMUG Forest Plan record of decision, shall be applied.”

The Organizations are unable to reconcile this decision with the fact the 2013 LCAS clearly states it has superseded the 2008 Southern Rockies lynx amendment and the USFS, USFWS, BLM, CPW and NPS experts recognize the current format, without goals and objectives is the most effective manner to manage the lynx.

The failure of the GMUG lynx management to even arguably comply with best available science is evidenced by the failure to recognize that not all habitat is created equal, and such recognition has become critical to species management of all kinds. While a detailed discussion of all the efforts to identifying habitat based in quality is too long for these comments, the Organizations believe a brief review is warranted. USFWS regulations now require significantly more information around habitat value in the listing of a species and designation of critical habitat. Recent planning around the Greater Sage Grouse went so far as to create three categories of habitat mainly: Priority, occupied and modeled but unoccupied habitats for the Grouse. In addition to these new categories, USFWS,BLM and USFS provided hundreds of pages of guidance documents to allow managers to plan accordingly. 18

The entire GMUG objective for lynx management under a single standard conflicts with the 2013 LCAS, which clearly requires two separate management standards, one for Core habitat areas and one for areas of lesser usage by the lynx. The overall intent of the 2013 LCAS is clearly identified as follows:

“…conservation efforts for lynx are not to be applied equally across the range of the species, but instead more focus is given to high priority areas: the core areas. Further, we combined secondary areas and peripheral areas (which were also identified in the recovery outline) into one category, because they have similar characteristics and management recommendations. The intent is to place more emphasis on protection of the core areas, which support persistent lynx populations and have evidence of recent reproduction, and less stringent protection and greater flexibility in secondary/peripheral areas, which only support lynx intermittently.” 19

The Proposal proposes to simply ignore that best available science for all species is now managing based on the differentiation of habitat quality, and the Proposal seeks to manage management all lynx habitat under a single standard as follows:

“Objectives

FW-OBJ-SPEC-50: Within 3 years of plan approval, update mapping that identifies snow-compacting activities, including designated and groomed routes and areas of persistent, winter-long snow compaction within each lynx analysis unit.” 20

The concept of LAU being of different quality or value is simply never even mentioned in the Proposal despite this being one of the cornerstone changes in the 2013 LCAS. The failure of the Proposal to utilize basic management tools for planning, such as priority habitat, modeled but unoccupied habitat and other classifications of habitat is deeply troubling and symptomatic of the complete failure of the proposal to be based on science as these tools are now commonplace species management tools as exemplified by listings and reviews of the Greater Sage Grouse, Gunnison Sage Grouse, numerous species of trout. This is habitat management 101 for all species and must be reflected in the Proposal. The failure to utilize basic tools such as this is problematic.

In addition to the failures noted above in the Proposal, the Organizations most painful example of the application of badly out of date research for lynx management is reflected in the following management standard:

“Guidelines

FW-GDL-SPEC-53: To maintain snowshoe hare occupancy and the lynx competitive advantage over other predators during winter, concentrate recreation activities and manage over-the-snow winter travel routes for no net increase in snow compaction at the scale of each lynx analysis unit.” 21

The concept of “no net gain” is the shorthand summary of the 2000 LCAS standards for OSV. This was specifically superseded by the 2008 Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment and again by the 2013 LCAS. In the Lynx blueprint efforts, this theory was repeatedly identified as one of the major failures of the entire lynx management process and is now diverting partner and management resources away from primary threats to the species. This badly outdated summary simply needs to be removed and updated with best available science on lynx management.

The Organizations would also note that almost every standard that is applied for lynx management in appendix 2 of the Proposal is directly cut and pasted from the 2008 SRLA and to avoid overly lengthy comments are not included in this document. No mention of the fact that the SRLA has been clearly superseded as a management tool is ever made.

The Organizations wanted to highlight some of the more significant changes in lynx management standards in the 2013 LCAS including:

- Recreational usage of lynx habitat is a second level threat and not likely to have substantial effects on the lynx or its Previous theory and management analysis had placed a much higher level of concern on recreational usage of lynx habitat; 22

- Lynx have been known to incorporate smaller ski resorts within their home ranges, but may not utilize the large Dispersed motorized recreational usage certainly does not create impacts that can be equated to even a small ski area; 23

- Road and trail density do not impact the quality of an area as lynx habitat; 24

- There is no information to suggest that trails have a negative impact on lynx; 25

- Snow compaction from winter recreational activity is not likely to change the competitive advantage of the lynx and other predators; 26

- Snow compaction in the Southern Rocky Mountain region is frequently a result of natural process and not recreational usage; 27

- Winter recreational usage of lynx habitat should only be “considered” in planning and should not be precluded given the minimal threat this usage poses to the lynx; and 28

- Failing to manage habitat areas to mitigate impacts of poor forest health issues, such as the spruce and mtn pine beetle, is a major concern in lynx habitat for a long 29

The conflict between FW-OBJ-SPEC-50 and the conclusions that snow compaction is a natural process, not recreational usage and that recreational activity does not alter the competitive advantage of the lynx could not be more direct. Again, the conflict between FW-GDL-SPEC-53 and the fact the LCAS clearly states there is no competitive advantage for lynx regarding other predators is again immediate and unresolved.

The Organizations vigorously assert that the Proposal must be amended and updated to apply basic management tools for species that are now recognized as best available science for the management of all species, such as identifying priority and secondary habitat areas and managing these in accordance with those basic tools. In addition to the implementation of best available science generally, the Organizations submit that the Proposal is in direct conflict with numerous specific management standards specifically stated in the 2013 LCAS and this must be corrected as well.

9. Winter travel boundaries must be reviewed and amended to reflect current management and provide quality recreational opportunities for all uses.

The Organizations are VIGOROUSLY opposed to the significant closures and restrictions to OSV management generally on the southern portions of the GMUG in the Proposed Winter ROS from the current winter travel planning for the GMUG. An example of such a change would include the proposed complete exclusion of OSV usage between US 550 and CO 145, the significant changes around Lake City for OSV access and the significant reductions in OSV access throughout the southern portion of the Forest more generally. These are highly valued recreational opportunities for the OSV community and the proximity to these opportunities represent a significant reason that many of our members have chosen to live in these areas.

This Proposal is highly frustrating to the OSV community as the GMUG has successfully managed OSV recreation on the forest for decades without any real controversy and provided world class opportunities for all users. We are simply unable to develop a fact pattern where any of the proposed management could be justified and believe the current proposal is significant step backwards in the otherwise successful partnership that has existed on the GMUG between the OSV community and USFS for decades. This is unfortunate as this Proposal will simply complicate any discussions on OSV issues moving forward as the seed of distrust has been sewn between the parties and that will be hard to resolve.

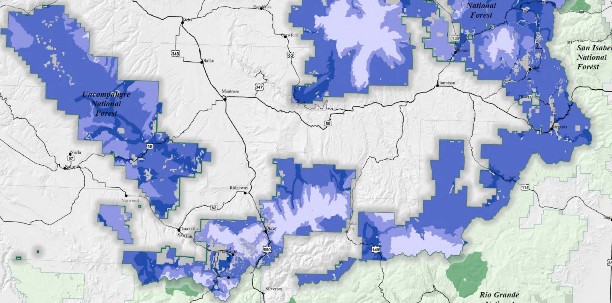

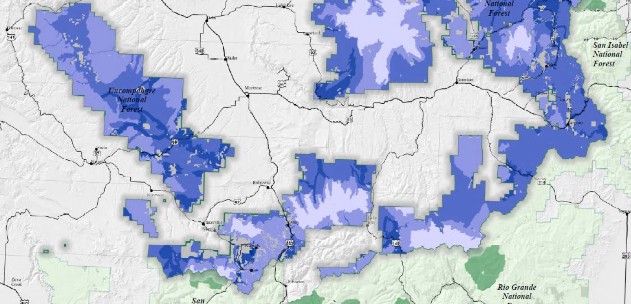

Current OSV management

Proposed OSV management

Not only are we deeply opposed to the landscape exclusion of OSV from vast portions of the GMUG where world class OSV opportunities have been permitted without major concerns for decades, the Organizations are also frustrated by the fact that many of our local clubs have partnered with the USFS in providing these opportunities, through grooming, maintenance and other issues. Despite these partnerships not a single club was contacted to discuss possible negative impacts to their desired recreational experience from proposed changes or to possibly discuss areas they may want to see reopened in the RMP to OSV travel. This really sends the WRONG message to Organizations and clubs that have partnered with the USFS for decades regarding both the value of their concerns about their sport but also the value of the partnership to land managers.

The long-term negative impacts of the Proposal for OSV travel are compounded by the directly conflicting messaging from the USFS regarding the value of partnerships and sustainable recreation. While the national USFS message through the Sustainable Trails Program and Partnerships efforts required by the National Trails Stewardship Act of 2016 30 continues to be partners matter, and partners should be expanded, the development of the Proposal is at direct odds with the National message. In Colorado, the OSV community came together in the 1970s to partner with GMUG planners and provide funding and volunteers to improve winter recreational opportunities for all through grooming of routes entirely at the user’s expense. This partnership was expanded in the 1980’s to include summer recreation and combined is now providing more than $1,000,000 annually to the GMUG for the benefit of all recreational users. No other partner even comes close to this level of support for the USFS efforts. The motorized community was collaborating for sustainable opportunities far before these were targeted for development by the USFS. Despite the motorized users being 50 years ahead of the USFS on this issue, no communication or discussion with existing motorized partners on what they might like to see in an RMP has occurred. We truly believe this is not the intended message of this portion of the RMP, but the message has been sent regardless of the intent and now we are forced to try and pick up the pieces.

Moving forward from the auspicious start the OSV community has now been provided, the Organizations would ask that the USFS review any preferred alternative for OSV management to ensure that there are opportunities for all usages on the GMUG in the winter. If there is a need to close an area to OSV, the basis must be provided in an understandable and discussable basis for any changes. This analysis is tragically lacking in the Proposal right now. The Organizations would also ask that USFS explore areas that have been historically closed to OSV to see if they could be reopened in the Proposal as there have been significant changes in many standards since the development of the forest level travel plans. The Organizations vigorously assert that attempting to work collaboratively from the current proposal would be totally ineffective and probably viewed as insulting by the OSV community due to the huge closures that are proposed and lack of discussion around why these proposals might be necessary.

After a far more balanced proposal is developed by the USFS planners to provide recreational opportunities for all users, the OSV community would welcome the opportunity to meet with GMUG personnel to discuss the revised proposal in detail. This could occur at the quarterly meetings held by CSA in Glenwood Springs or these meetings could be held with clubs directly as part of their meetings throughout the GMUG.

10. Management of wildlife concentration areas must be more flexible and explored through tools other than the

The Organizations have partnered with GMUG planners and CPW to develop seasonal closures for routes and areas for a wide range of wildlife issues, including species winter range, calving areas and resource concerns at the local level for decades. In addition to this collaborative planning, the motorized community has also supported this management with the direct funding of signage, gates and educational materials for users in order to help build understanding for why a seasonal closure is in place and why it is valuable.

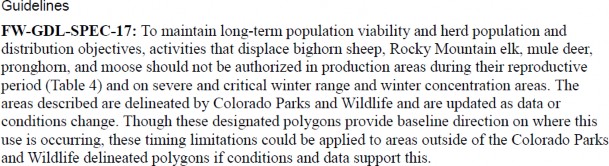

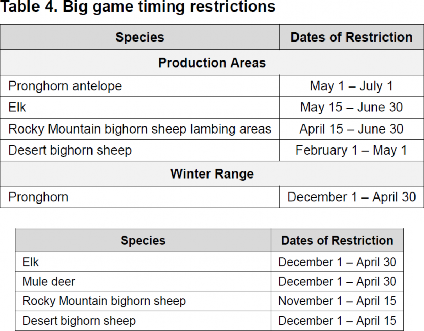

It has been our experience any closures are most effective when they are developed at the local level and reflect the actual dates the particular species are using an area. Nothing will undermine public support for seasonal closures and other wildlife restrictions faster than closing areas to recreation when there have not been the species of concern in the area for extended periods of time. This type of information is simply most effectively developed at the local level, and as a result the Organizations must question the benefit of placing hard dates for particular species in the RMP, such as is now proposed for the GMUG:

31

The Organizations are simply unable to understand the benefit of placing this type of information in the RMP rather than addressing these types of issues in a manner that is more flexible, such as the more localized travel planning process that the GMUG currently has in place. The Organizations believe that the ability to change these types of dates is very important to the effective management of species and in years where there are highly variable amounts of snow, wildlife may not move into areas or calve at different times of the year. This type of movement is not effectively managed at the RMP level as anytime there was a desire to adjust those dates for a local issue, this would require an RMP amendment. That simply does not make sense.

In addition to the list of species not making a lot of sense from a purely management perspective, the list also appears to be incomplete, as Sage Grouse and numerous species of fish are not included in the list. Why was the list limited to big game only? Clearly any management tools should be as broad in scope as possible to ensure that all species appear to be treated equally under the management process. We must further question the value of any list that is simply incomplete in terms of its scope. While we are simply puzzled by the partial scope of the Proposal and the inflexibility of the dates as a management tool if they are in the RMP, the Organizations continue to support wildlife management in the travel process.

The Organizations also believe that the placement of these dates in the RMP complicates management over the 30-year life of an RMP the Colorado climate will have changed and we really are not able to forecast what this might look like over the life of the RMP. Again, this situation weighs in allowing a large amount of flexibility in addressing this issue and placement of the standards in the RMP would require an amendment of the RMP to change dates. This process simply is not facilitated by placing standards that will need to be adjusted in the RMP and the Organizations are concerned that this type of standard would become another standard that is a barrier to management towards the end of the RMP life rather than a successful streamlining effort.

11a. We continue to oppose Gunnison Public Lands Initiative to date.

The Organizations again wish to memorialize our ongoing concern over and opposition to the Gunnison Public Lands Initiative (“GPLI”) process, as there has again been extensive press around the efforts and release of a final version of this recently. It has been our experience that this process was not about actually involving the public to develop a balanced legal plan for the Gunnison Valley but rather was an effort by a small group to create the appearance that there was public involvement to support an agenda that had been developed by them prior to any public involvement. Too often the public was not provided notice of meetings or other basic materials for public meetings like agendas and minutes were never available and those of our members that were able to locate a meeting were treated poorly and any input provided was overlooked after discussions started from a position that areas should be Wilderness unless that person could prove otherwise. Clearly, that is not the way to engage the public in questions of land management and as a result really draws the value of this proposal into question.

In discussions with many of the county officials representing counties adjacent to Gunnison County, we have found there to be overwhelming opposition to the GPLI proposal from these adjacent counties. Initially, many of these counties raised concerns about the failure of the GPLI efforts to engage those counties on the management of public lands outside Gunnison County. Rather than engaging with these counties to address concerns, GPLI representatives simply reduced the proposal to Gunnison County lands only assuming that this was sufficient. For reasons that remain unclear GPLI simply assumed that management of public lands on the boundary areas of Gunnison County would not impact adjacent lands in other counties. That assumption has proven to be less than accurate and has resulted in significant conflict between the counties that never existed previously.

It should be noted that after a review of the Gunnison County Commissioners meeting minutes for the years after they convened the GPLI, GCC met with numerous adjacent counties to attempt to build support for GPLI. This would include meeting with the Town of Marble on Feb 2, 2017 meeting with Hinsdale County on September 5, 2017 and Delta County on July 11, 2017. None of these counties supported the recommendation and we believe this is an indication that significantly more work needs to be done on the GPLI recommendation.

It should also be noted that the Organizations submitted extensive comments to the GPLI and asked to meet with GLPI representatives. Despite being in the Gunnison area repeated times over the last 18 months since the comments were submitted, we were unable to meet with anyone. Representatives were always busy or calls were made after trips to the Gunnison area had concluded. Also, our local clubs that did have limited participation in the GPLI process are now struggling to clarify basic steps of any large discussion, mainly that their participation in the process does not mean than they endorse the conclusion. That is an entirely separate step and any approval of the final conclusion of GPLI must be done by the Organizations Board and members. Despite requests to allow such a vote the GPLI continues to assert that the motorized community supports the conclusions that have been reached. We are simply unsure of how that conclusion was reached.

The failure of the public process around the GPLI efforts have led to conclusions that are rather comical in nature. GPLI asserts that the Curecanti/Blue Mesa Reservoir should be managed as priority Sage Grouse habitat despite the large number of developed campsites that have existed in this area for decades and the area was not identified as priority grouse habitat for either the Greater or Gunnison Sage Grouse. We must wonder about that conclusion, especially since most the area was clearly found to be unoccupied.

Another significant concern about the basic direction of the GPLI efforts relates to the priority management concerns in the conclusions. Almost every management restriction relates to motorize access to particular areas and the GPLI essentially would prohibit the construction of roads and trails in the Gunnison Valley in the future. Again, the Organizations must question the basis for this type of a conclusion as any assertion that multiple use recreation is the major impactor of Gunnison Valley landscapes is probably without merit and fails to address the fact the multiple use community is also the single largest funding partner with the USFS to address many landscape level challenges.

The third example of the complete failure of the GPLI process is the fact that the GMUG identified several priority forest health treatment areas across the forest with their SBEADMR efforts concluded in 2015. Under GPLI, each of these areas would now be managed as Wilderness rendering the decisions and their NEPA review scientific basis irrelevant. This simply makes no sense.

11b. GPLI and Colorado Sunshine Laws violations.

In a very troubling turn of events surrounding the GPLI, which was convened by Gunnison County, in no way complies with Colorado Sunshine Law 32 requirements for a public effort that is being convened by what the statute refers to as an “other public agency”. Given the GPLI has claimed broad public support and collaboration, any violation of the Sunshine Laws would be concerning. Any claim of public support and transparency in the process is removed by the fact there does not appear to have been any attempt to publish hearing notices or minutes in any publicly noticed venue such as a newspaper.

Based on a review of the statute as Gunnison County Commissioners convened the GPLI group to obtain public input regarding management of public lands and development of possible statutory language. In addition to the GPLI efforts being convened by Gunnison County, County commissioners served in ex officio roles with GPLI, periodically reported back to the entire county commission, approached other counties regarding support for the efforts and sought out funding for the project. Any one of these actions was sufficient to trigger the Colorado sunshine laws, which clearly made the process entirely subject to all notice and record keeping requirements of the statute. For reasons that remain unclear, the requirements of the Colorado Sunshine law were simply never complied with.

Additionally, the Organizations put GPLI o written notice May 7, 2018 that the public process surrounding the effort needed significant improvement. Rather than address these basic concerns, the Organizations concerns about the complete lack of transparency in the process were never addressed. the Organizations were never contacted to substantively discuss our concerns on how to improve the “public” process around the effort. This open disregard for public input in the alleged open public process of the GPLI continued as Gunnison County recently rubber stamped the GPLI recommendation and is now submitting it to the USFS as their “community” recommendation and is pursuing federal legislation based on its recommendation.

As the Gunnison County Commissioners only recently announced this decision, the Organizations have not finalized research efforts on this concern but we expect to have a notice of intent drafted and served on the County in the near future.

12. Conclusions.

The Organizations welcome the opportunity to provide our input prior to the commencement of the formal NEPA process governing development of the RMP. Our preliminary thoughts for the Proposal would include:

- We welcome the brief nature of the RMP and the opportunity to comment on the Proposal prior to the commencement of the formal NEPA process;

- Presentations to the public in this pre-review have sometimes conflicted with the RMP provisions;

- Better maps for the Proposal are needed;

- Revisions of existing travel management decisions should occur on a more localized level than a forest plan;

- There needs to be flexibility in the ROS management standards for non-motorized areas;

- The Winter ROS recommendations needs extensive review and amendments due to closure of most of the southern portion of the forest to OSV usage;

- Lynx habitat needs to be managed in accordance with the 2013 LCAS;

- Continental Divide Trail management must comply with National Trails System Act mandates and the Continental Divide Trail Plan;

- The Organizations are unsure what benefit is sought to be achieved by placing seasonal closure dates for a limited number of species in the RMP; and

- The Organizations remain opposed to the sham public process of the GPLI and any recommendations from this process as any assertion of public process is a direct violation of the Colorado Sunshine Act for committees convened by a

The Organizations would welcome a discussion of these opportunities and any other challenges that might be facing the GMUG moving forward at your convenience. Please feel free to contact Don Riggle at 725 Palomar Lane, Colorado Springs, 80906, Cell (719) 338- 4106 or Scott Jones, Esq. at 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont, CO 80504. His phone is (518)281-5810 and his email is scott.jones46@yahoo.com.

Sincerely,

Scott Jones, Esq.

CSA Executive Director

TPA & COHVCO Authorized Representative

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

2 See, GMUG RMP at pg. II-31. (1983)

7 See, United States v. Boisdoré’s Heirs, 49 U.S. (8 How.) 113, 122 (1850).

8 See, Green v. Bock Laundry Machine Co., 490 U.S. 504, 528 (1990). For a more complete review of this issue please see, Congressional Research Services: Statutory Interpretation: General Principals and Recent Trends; September 24, 2014

11 See, HRep 1631 at pg. 3873.

12 See, USFS, Continental Divide National Scenic Trail Comprehensive Plan 2009 at pg. 19.

13 See, The 2009 Continental Divide National Scenic Trail Plan; pg 15

16 See, Interagency Lynx Biology Team. 2013. Canada lynx conservation assessment and strategy. 3rd edition. USDA Forest Service, USDI Fish and Wildlife Service, USDI Bureau of Land Management, and USDI National Park Service. Forest Service Publication R1-13-19, Missoula, MT. 128 pp. at pg. 1. (hereinafter referred to as the 2013 LCAS”). We have included a complete copy of this document for your reference with these comments.

18 See, https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/sage-grouse-habitat-assessment-framework.pdf

30 See, NATIONAL FOREST SYSTEM TRAILS STEWARDSHIP ACT; Public Law 114-245 at §4.