Most of you are familiar with the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance – but if you are not you should be. SUWA is behind efforts to continually restrict access to public lands for all types of recreation. This recent article in Range Magazine is well worth your time – it paints a really good picture of what we are up against in the struggle to protect access to our public lands in Utah and all over the West.

Reprinted with permission from Range Magazine and Marjorie Haun.

RANGE MAGAZINE

SUMMER 2021

Utah’s biggest Green group is caught between protecting wilderness and big tourism.

By Marjorie Haun

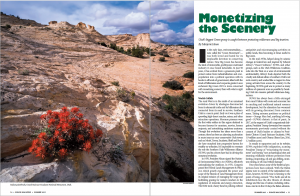

Indian paintbrush, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Utah.

In the early days, environmentalism—now called the “Green Movement”—was both loved and hated for its implacable devotion to conserving nature. Now Big Green has become the kind of immovable, profit/power-motivated industry it once found detestable. In just 50 years, it has evolved from a grassroots push to protect nature from industrialization and overpopulation into a political operation with its hooks in all levels of government, allied with the kinds of billionaires and corporate giants it once eschewed. Big Green 2021 is more concerned with monetizing scenery than with what is right for the environment.

Worlds Collide

The rural West is in the midst of an unnatural evolution driven by ideologies disconnected from its elemental truths and by billionaires disconnected from its need to survive. Southern Utah is a case in point. Early on it was a place of sprawling high-desert ranches, mines, and other extraction operations. Mormon pioneers were the first white settlers in this region destined to become famous for uranium, movies, homey outposts, and astonishing sandstone anatomy. Though this evolution has taken more than a century, there has been an alarming acceleration in recent years as once-conservative Utah towns such as Moab, Torrey, Escalante, Bluff, and Boulder have morphed into progressive havens for wealthy ex-urbanites. It’s impossible to overstate the role the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA) and its cohorts have had in driving this unnatural evolution.

In 1970, President Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), effectively nationalizing the outdoors. In 1976, Congress passed the Federal Lands Management & Policy Act, which greatly expanded the power and scope of the Bureau of Land Management from its original mission of managing the range and facilitating grazing for western ranchers to the regulation of minerals and energy extraction. The BLM took a heavy hand in policing cultural antiquities and micromanaging activities on public lands, thus becoming at times useful to Big Green.

In the mid-1970s, helped along by seismic changes in federal law and inspired by Edward Abbey’s “Desert Solitaire,” SUWA and other groups, such as the Utah Wilderness Coalition, rode into the West on a wave of environmental sentimentality. Abbey’s book depicted both the cruelty and delicate allure of southern Utah’s red rock country and worked like a magnet to draw young activists from across the country. In the beginning, SUWA’s goal was to protect as many millions of quiescent acres as possible by breaking Utah into massive piebald wilderness designations.

SUWA has always been a little estranged from rural Utahns with roots and economic ties to ranching and traditional natural resource development, but the alienation has worsened with its growing disconnect from common sense. Taking extreme positions on political issues—Orange Man bad, anything left-wing good—SUWA’s rhetoric is that of panic. In 2017, at the request of Utah’s congressional delegation, President Trump downsized two massive monuments previously created without the consent of Utah’s leaders or citizens by Presidents Clinton (Grand Staircase-Escalante, 1996, 1.9 million acres) and Obama (Bears Ears, 2016, 1.3 million acres).

In emails to supporters and on its website, SUWA exploded with indignation, accusing President Trump of “eviscerating the monument” and leaving “rare archaeological sites and stunning wildlands without protection from looting, prospecting, oil and gas drilling, uranium mining, or off-road vehicle damage.”

Four years hence, none of the hysterical projections have been realized. With the Biden regime now in control of the nationalized outdoors, however, SUWA’s tone is fawning to the point of being comical: “The Earth and all its inhabitants face the dire threats of climate change and the loss of nature, including extinctions. And in its first 10 days, the Biden administration has already taken meaningful steps to address those threats. It isn’t our job at SUWA to cheerlead for a particular administration; it’s our job to push them to go further. But we are very encouraged—even excited—by the Biden administration’s start.”

But neither its extreme partisanship nor its disconnect from the grassroots is a problem for SUWA’s bottom line. With its offices in D.C. and Salt Lake City, assets of over $16 million and an annual revenue of nearly $6 million, reliable donations from billionaires, billionaires on its board of directors, and lucrative relationships with fashion designers and gigantic outdoor recreation companies such as Patagonia, REI, Black Diamond and Petzl, SUWA doesn’t need to appeal to working people in the rural West.

Shady Billionaires & the De-democratization of the Green Movement

Although Jeff Gibbs’ 2019 documentary, “Planet of the Humans,” came to the odious conclusion that only mass human depopulation would save planet Earth, it showcased how in the last two decades Big Green has sold out to corporate interests and wealthy donors with their own profit motives. Not only does the onboarding of billionaires de-democratize groups such as SUWA, but it also makes them dependent on venture capital and sometimes ill-gotten wealth. There are dark chapters in the histories of SUWA’s most high-profile billionaire board members Hansjorg Wyss and Bert Fingerhut.

In 2012, Mina Kimes penned a report for Fortune magazine titled, “Bad to the Bone: A Medical Horror Story,” in which Hansjorg Wyss plays the role of supervillain. In the early 2000s, Wyss’ medical device company, Synthes, began testing Norian X-R, a bone-growing compound, using illegal trials on human subjects. Synthes promoted Norian X-R for use in spinal surgeries, a procedure for which it had not been approved. Johnson & Johnson purchased the compound, which started killing patients almost as soon as it hit operating rooms. Four Synthes executives were indicted and convicted on charges related to “off-label marketing,” but Wyss went untouched. In 2021, Wyss continues to make sizable donations to SUWA and sits on its board of directors.

Bert Fingerhut, a billionaire Wall Street securities analyst and Green activist, moved to Aspen, Colo., in 1983 and connected with several groups including SUWA. In 2007, while serving as director of SUWA, he pled guilty in federal court to numerous charges of securities fraud. Mark Ristow, an associate of Fingerhut’s and then SUWA treasurer, was indicted as well. According to a column by Joe Bauman in Deseret News: “Ristow, 62, a resident of Indianapolis, was a SUWA director as well as treasurer for the environmental activist group headquartered in Salt Lake City. Like Fingerhut, Ristow pleaded guilty to organizing an elaborate scheme to defraud savings banks and depositors.” This is not the stuff of grassroots conservation.

In a 2006 article, environmentalist and former SUWA board member Jim Stiles detailed an instance showing how the influence of billionaires such as Wyss, Fingerhut, and venture capitalist David Bonderman, who sits on the boards of the Wilderness Society and Grand Canyon Trust, has de-democratized the environmental movement.

“The Wyss donation was particularly fortuitous,” Stiles wrote. “Its founder, Swiss-born Hansjorg Wyss, became a member of SUWA’s [b]oard of [d]irectors in 1996 and is its current chairman… In 2004, SUWA had almost $5 million in ‘net assets and fund balances,’ including $2.5 million in ‘savings and temporary cash investments,’ nearly $300,000 in ‘non-interest-bearing cash,’ and about $1 million in ‘stocks and mutual funds.’ With all those assets, a gala party is planned in May as a tribute to Wyss. The event, to be held in New York City, will cost about $100,000. But according to [SUWA director Scott] Groene, ‘it’s a fund-raising event…[it] will raise us money.’ How much money is enough? No one can fault SUWA for its good fortune, but Utah’s most prominent environmental organization is starting to look more like a bank. And while its coffers have grown, membership, according to a SUWA source, has fallen to less than 14,000.”

Big Tourism & Cognitive Dissonance

Edward Abbey wrote in “Desert Solitaire” (1968): “Industrial Tourism is a big business. It means money. It includes the motel and restaurant owners, the gasoline retailers, the oil corporations, the road-building contractors, the heavy equipment manufacturers, the estate and federal engineering agencies and the sovereign, all-powerful automotive industries.” Twenty-five years after he penned those words, Abbey’s disciples would come to embrace the “big business” about which he cautioned.

Monetizing the scenery brought with it the promise of tourist-generated wealth that would supplant mining, oil and gas jobs and revenues. The amenities economy solution became the rose-colored-glasses selling point for SUWA’s overarching wilderness bill. Seeing an area for compromise and the possibility of a reliable flow of tourist dollars into their towns, a lot of locals went along with the scheme. What followed was a boom of small locally owned restaurants, outfitters, rental shops, retailers, and guide services that quickly became dependent on the marketing of Utah’s beautiful places. Some sectors boomed more than others. Then Big Green backtracked.

Fast-forward to 2021, and red rock tourism is now dominated by off-road-vehicle enthusiasts. After embracing the amenities economy solution in the 1990s, SUWA now stands in opposition to the OHV (off-highway vehicle) sector of tourism. But SUWA wields political clout and its dissonant agenda threatens to shut down a large sector of the local economy. Under pressure from SUWA, the Moab and Grand County councils recently banned large OHV events in the area and are leaning heavily on nearby San Juan County to do the same.

Dispersed camping—an iconic outdoor activity enjoyed by all demographics—is also on SUWA’s hit list. In 2020, SUWA petitioned the Bureau of Land Management to restrict off-roading and dispersed camping in the San Rafael Swell region, a vast range of sagebrush and red rock in central Utah. Under the purview of President Trump’s BLM director, the agency rejected SUWA’s petition.

In the SUWA universe, however, the scope of acceptable economic alternatives is narrowing. Arbitrary bans won’t hurt its wealthy donors, staff of attorneys, or billionaire board members, but it may be the death of local businesses that serve off-road and camping enthusiasts. Frankly, it’s hard to know what to do. Millions of hikers and thousands of mountain bikers on unregulated trails…good. Families with ATVs camping by the creek…bad.

Political Puppet Masters

Today SUWA is immersed in politics and, like all savvy political organizations, it’s playing the long game. The demographic shift needed to achieve its prime goal of a federal bill that would put tens of millions of acres into a restricted wilderness designation forever is underway. With progressives, many favored or employed by SUWA, now dominating commissions in both Grand and San Juan counties, SUWA is neither looking for, nor does it need, the consent of the governed.

In 2017, following a decades-long series of lawsuits brought by the Navajo Nation against San Juan County, federal Judge Robert Shelby took the unprecedented action of federalizing a local election and redrawing voting districts. In doing so, Shelby gave majority control of two of the county’s three districts to the Navajo Nation, which comprises a small fraction of the county’s landmass.

During that same time SUWA founded and funded the Rural Utah Project, with the goal of ensuring that Democrats would dominate local government. Using identity politics to recruit minority voters, RUP helped to flip San Juan County in 2018. The “get out the vote” arm of SUWA/RUP has the kind of money that grassroots political organizations could only dream of. SUWA’s activities are creating a political serfdom in which majority conservative/Republican counties are being controlled by progressive politicians enacting agendas disconnected from the history and traditions of the people.

Liz Thomas, a SUWA field attorney who lives in Moab in Grand County, has been in fact writing policy for the county commis¬sion in San Juan County. Documents obtained from the county show that Thomas has ghost-written at least 12 resolu¬tions from 2019 to the present. Her resolu¬tions are invariably put forth by one of the two progressive commissioners whom RUP helped elect in 2018: Mark Maryboy and Willie Grayeyes. Documents related to the county policy were emailed directly to the county administrator from Thomas with instructions to put them on the agenda. Recently, Thomas wrote a controversial reso¬lution asking Joe Biden to reestablish the rescinded boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument.

Using official letterhead, Thomas has written at least one response from San Juan County to the BLM. At one point, she was sending Commissioner Maryboy so many directives that the county administrator, Mack McDonald, made the following state¬ment in an email to Maryboy: “Is there a way when these come to you, that we can meet and review them with enough time so that we can fix these and have the [c]ounty [a]ttorney review them?” The people be damned; SUWA is steering policy in San Juan County.

America’s Red Rock Wilderness Act

Since it was introduced into Congress by Wayne Owens in 1989, SUWA’s defining piece of legislation, America’s Red Rock Wilderness Act, has doubled the landmass it would encompass from around five million acres to nearly nine million acres. It would pack such a severe punch to Utah’s rural economies that few legislators have wanted to touch it. Even Obama’s Interior Department regarded it as radioactive. But with Biden now occupying the White House, SUWA may get its prize. In its currently proposed form, ARRWA would lock up a large percentage of southern Utah’s most resource-rich lands into wilderness des¬ignations in perpetuity. SUWA’s radical pro¬posal, however, may be small potatoes when compared to the Biden regime, which has recently announced that it intends to “pre¬serve” anywhere from 30 to 50 percent of America’s lands. With one-third of the U.S. landmass now under federal control, and another third to one-half removed from eco¬nomic production, American ranchers, farm¬ers, miners, oil and gas workers, and the families they feed could fade into history.

The Pendulum

With decades of activism and millions of dol¬lars, SUWA has transformed Utah’s political landscape. Nonetheless, there is organized and growing opposition to its initiatives. Pres¬ident Trump’s downsizing of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in 2017 dealt a painful political blow. Now, even with the Biden regime on its side, SUWA has an uphill battle to enlarge the national monuments due to profound opposition at both state and local levels.

In 2017, SUWA used “open meetings” rules to sue three counties—Kane, Garfield and San Juan—whose commissioners met with Trump’s then-Interior secretary, Ryan Zinke, about the monuments. In August 2019, the court rejected the lawsuit and fined SUWA for $50,000 in legal fees. Utah’s Blue-Ribbon Coalition/Share Trails, comprised of small businesses, outdoor recreation/OHV clubs, and individuals, has successfully rebuffed many of SUWA’s recent efforts to close roads and prohibit motorized access on federal lands. And most recently, a federal judge rejected SUWA’s bid to stop a helium drilling operation on BLM land in Labyrinth Canyon near Lake Powell.

To a degree, transplanted ex-urbanites have changed demographics in southern Utah. Nevertheless, SUWA remains largely alienated from the working people of the region. With its political puppeteering exposed and a gauntlet of finicky criteria for outdoor activities to gain its acceptance, SUWA’s clout remains dependent on big-dol¬lar outside support. Giving its oblations to bil¬lionaires, big corporations, and pop-culture elites, SUWA is guilty of anti-rural bigotry, a cynical disregard for the people whose des¬tinies it seeks to control.

The average yearly income for people who live and work in southern Utah is around $42,000 per household. SUWA’s payouts are six figures. In 2018, SUWA director Scott Groene earned $163,000 in salary and bene¬fits. Attorney Steven Bloch took home $126,000. SUWA paid one legal contractor $411,355, and the total payroll for that year was $1,873,000. Finally, with most of its activists coming from outside southern Utah, and its main offices in Salt Lake City and Washington, D.C., SUWA looms as a self-righteous crusader, sweeping down from on high to save rural Utah from the rural Utahns who live there. SUWA’s political extremism, dissonant objectives, erosion of its donor base, and disconnect from “roots Utahns” are a chink in this Big Green’s vainglorious armor.

Marjorie Haun is a freelance writer from southern Utah who shares with Jim Stiles both wonder and dread at the urbanization of the rural West.

Download Full article with images:

Monetizing the Scenery

Read the full magazine:

RANGE Magazine

Summer 2021