GMUG National Forest

Att: Planning team revision

2250 South Main Street

Delta, CO 81416

Re: GMUG Resource Management Plan Revision

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the input of the Organizations identified above with regard to the Proposed Revision of the GMUG RMP. We welcome this opportunity to provide input following the first round of public meetings addressing the proposed forest plan revision. We would like to provide input on a few components in the final RMP which we believe could streamline planning significantly moving forward, provide new information and address several issues that consistently arise early in the Forest Service planning process on other forests in the hope of partnering with the GMUG to develop an effective long-term plan for the forest. These comments are submitted as a supplement to the site-specific input provided from the local clubs on a wide range of issues, such as culvert size and future utilization of decommissioned roads as trails. The Organizations vigorously support the input from these local clubs.

Prior to providing initial thoughts and concepts on the development of the GMUG RMP, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization the 150,000 registered OHV users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA advocates for the 30,000 registered snowmobiles in the State of Colorado. CSA has become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling by working with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators. For purposes of this document CSA, COHVCO and TPA are identified as “the Organizations”.

As we discussed in far more detail in earlier submissions, there is a critical need to develop an RMP that is reasonably brief and easy for the public to use and understand. While we will not be discussing that issue in great detail in these comments, these goals and objectives remain critically important. The Organizations continue to support the recognition of the need to expand access on the GMUG in a thoughtful and planned manner for all recreational activity, as already recognized in the assessments.

In this round of comments, we are providing a detailed legal history of the lack of Congressional support for designation of exclusionary corridors around the Continental Divide Trail (“CDT”) and other routes designated under the National Trails System Act (“NTSA”). While we are not aware of this issue being raised in scoping to date, we are aware of the immense pressure on other forests to create such corridors. It is our position that such corridors are illegal under federal law and also fail to balance multiple uses along the trails inn violation of NEPA planning requirements.

In addition to outlining the extensive Congressional action that has been taken around the need to benefit all uses with an NTSA route, the Organizations have also provided a detail analysis of the extensive multiple agency reviews of possible Wilderness areas on the GMUG, many of which have been occurring since before the Wilderness Act was even passed by Congress. These multiple agency reviews have been heavily relied on in previous Congressional action designating Wilderness areas on the GMUG and also in releasing significant portions of the GMUG back to multiple use requirements and explaining why boundaries of designated Wilderness areas are in the locations are in the places that they are. This history is critically important given the fact that many of these areas found specifically unsuitable for Wilderness designations previously were again recommended for Wilderness designation in the draft 2007 RMP. The Organizations are aware such action is theoretically legally possible, the Organizations submit that such a recommendation is factually confounding and should be avoided.

These Congressional actions have often been the result of years of consensus building around the legislation that was passed in 1980 and 1993 and represents some of the largest collaborative efforts around land management in the states history. This level of collaboration is highly relevant as one of the consistent themes we have heard from land managers is the position that diverse groups should come together on tough issues and build a recommendation for resolution of the issue. With Wilderness on the GMUG, this consensus process has occurred and the Organizations are asking that land managers not disrupt this consensus management position by recommending Wilderness in areas where the consensus position, memorialized in federal law, is that the area is not suitable. The fact that one group did not get exactly what they wanted in the consensus position does not mean the consensus should be disrupted, despite posturing in draft legislation that there is some level of support for change in the consensus. The history of the legislative efforts since 1993 evidences a lack of political support for such a change rather than a basis for changes in management of these areas.

The final general issue we would like to provide input on is snow sciences around OSV management. The Organizations are all too familiar with the large amounts of unpeer reviewed citizen science that is now being submitted with regard to many USFS planning efforts, on what appears to be a position that there is no science on many of these challenges. The Organizations submit there is extensive science on most of these issues and that the peer reviewed high-quality science that is available does not support management of issues in the manner recommended in this citizen science. Rather the best available science supports existing management and highlights the low-quality nature of the citizen science being submitted, such as the fact that citizen researchers seek to recommend management based on snow depth but fail to prepare their research in a manner that even arguably complies with BMPS for snow depth measurement from the National Weather Service. Land managers must exhibit a high level of caution in relying on citizen science that fails to clear even such basic hurdles in the scientific process.

1a. Corridors around NTSA routes are illegal.

The Organizations have participated in a large number of planning efforts throughout the western United States where an unusual issue has come up in the planning process, mainly public pressure around the need to designate exclusionary corridors around routes designated under the National Trails System Act, which would be most commonly the Continental Divide Trail on the GMUG. The Organizations are surprised at this effort as the management of these routes has been a long-settled issue under federal law and not been a basis for significant concern on most forests in the Western United States. As a result, the entire concept of an exclusionary corridor is both creating a problem where on simply does not exist currently but also would be implementing management that Congress has specifically forbidden with numerous revisions of the NTSA. Any decisions with regard to the need for an exclusionary corridor or landscape exclusion of motorized usage from the CDT would be completely without basis in law or fact as more than 14% of CDT is currently on a motorized road and an unspecified percentage more is located on motorized trails and significant portion of the CDT are groomed for winter motorized recreational usage. All these management decisions have been in place for decades and operate without major conflict. The long history of successful management of these areas for the benefit of all is simply never addressed by those seeking a landscape level exclusion nor is the conflict between proposed exclusions and existing federal law resolved or even addressed by those seeking an exclusion. As a result, the Organizations are vigorously opposed to any closures of the CDT to multiple use. Congress has consistently moved to protect multiple use access to the CDT with ever amendment to the NTSA.

1b. Mandatory exclusionary corridors directly conflict with the Congressional language and intent when NTSA was passed.

The management of NTSA corridors and routes has a long and sometime conflicting management history when only 1968 legislation is reviewed but significant clarity in Congressional intent for management of routes and corridors is provided with the review of Congressional reports provided around passage of the NTSA in 1968. Significant clarity in addressing the Congressional desire for multiple use management has been added with every amendment to the NTSA since 1968. Multiple uses of corridors and trails was originally addressed in House Report 1631 (“HRep 1631”) issued in conjunction with the passage of the NTSA in 1968. While there are numerous Congressional reports referenced in the 2016 USFS CDT guidance, many of which have not been provided to the Congressional offices for release to the public, HRep 1631 is simply never mentioned despite it being a foundational document in the discussion.

HRep 1631 provides detailed guidance regarding the intent of the Legislation, and options that Congress declined to implement in the Legislation when it was passed. It is deeply troubling to the Organizations that USFS guidance relies on numerous legislative documents, many of which are unavailable to the public,[1] but this highly relevant legislative document is never addressed in the USFS Guidance. HRep 1631 provides a clear statement of the intent of Congress regarding multiple usages with passage of NTSA, which is as follows:

“The aim of recreation trails is to satisfy a variety of recreation interests primarily at locations readily accessible to the population centers of the Nation.”[2]

The Organizations note that satisfaction of a variety of recreation interests on public lands simply is not achieved with the implementation of any width corridor around a usage or trail. Rather than providing satisfaction for all uses, implementation of mandatory corridors will result in unprecedented conflict between users. This simply must be avoided.

While HRep 1631 is not addressed in 2016 USFS CDT guidance, the direct conflict of the agency guidance and this report simply cannot be overlooked. Much of the information and analysis provided in HRep 1631 is highly relevant to the authority of USFS guidance assertions that 1-mile corridors are mandatory or even recommended. HRep 1631 clearly and unequivocally states Congress declined to apply mandatory management corridors of any width in the Legislation. HRep 1631 states:

“Finally, where a narrow corridor can provide the necessary continuity without seriously jeopardizing the overall character of the trail, the Secretary should give the economics of the situation due consideration, along with the aesthetic values, in order to reduce the acquisition costs involved.”[3]

Congress also clearly identified that exclusionary corridors would significantly impair the ability of the agencies to implement the goals and objectives of the NTSA as follows:

“By prohibiting the Secretary from denying them the right to use motorized vehicles across lands which they agree to allow to be used for trail purposes, it is hoped that many privately owned, primitive roadways can be converted to trail use for the benefit of the general public.”[4]

HRep 1631 clearly addresses the intent of Congress, and the internal Congressional discussions regarding implementation of the NTSA provisions for the benefit of all recreational activities as follows:

“however, they both attempted to deal with the problems arising from other needs along the trails. Rather than limiting such use of the scenic trails to “reasonable crossings”, as provided by the Senate language, the conference committee adopted the House amendment which authorizes the appropriate Secretaries to promulgate reasonable regulations to govern the use of motorized vehicles on or across the national scenic trails under specified conditions.”[5]

Rather than conveying the clear intent of Congress to avoid corridors as a part of management of an NTSA route, on page one of the 2016 CDT guidance clearly states that such a corridor is the preferred management tool, stating as follows:

“The CDT corridor/MA should be wide enough to encompass the resources, qualities, values, associated settings and primary uses of the Trail. The 0.5-mile foreground viewed from either side of the CDT must be a primary consideration in delineating the CDT corridor/MA boundary (FSM 2353.44b (7)).”[6]

The Organizations are simply unable to theorize any situation where the intent of Congress in passing the NTSA and the 2016 CDT guidance can be reconciled as Congress specifically stated that corridors should not be applied and managers retain authority to address site specific issues and challenges. This is deeply concerning given the fact that if Congress has specifically looked at a management tool and specifically declined its application, any implementation of such a tool in management is problematic. This type of direct material conflict is not mitigated with the passage of time especially when the clearly stated intent of Congress was to satisfy a variety of recreational interests with the passage of the NTSA. The Organizations vigorously assert that only those interests protected by the corridor would be satisfied with a corridor, and this must be avoided.

1c. The recommended 1-mile corridor around NTSA in 2016 USFS guidance directly conflicts with 1983 NTSA amendments.

The balancing of multiple uses on NTSA routes and adjacent corridors has been an issue that Congress has struggled with for an extended period of time and repeatedly addressed with growing clarity. As clearly stated in HRep 1631, when the NTSA was passed Congress sought to balance all uses in the vicinity of any route designated under the NTSA. Given the subsequent amendments to the NTSA the need to balance all uses is a concern that Congress has consistently and repeatedly addressed with higher levels of clarity in the NTSA. Unfortunately, this does not appear to be the first time when agency planning sought to implement restrictions on other usages around a NTSA route in contradiction to federal law.

Subsequent to the passage of the NTSA in 1968, Congress further refined and clarified the management practices for public lands with the passage of Federal Land and Policy Management Act (“FLPMA”) of 1976. While FLPMA did not specifically address the relationship of its provisions with the NTSA, FLPMA altered the entire landscape of federal lands management and the implementation of multiple use mandates for the agencies. Subsequent to the adoption of FLPMA, the NTSA was amended in 1983 to clarify that FLPMA and multiple use principals controlled the management of not only the footprint of NTSA routes but also the corridors around those routes with the passage of Public Law 98-11. The relationship between the passage of PL 98-11 in 1983 further clarifying Congressional desires that the NTSA was to benefit a wide range of interests and specifically stated the concept of corridors and crossing points were not acceptable concepts for management of NTSA previously. The response of Congress was the 1983 NTSA amendments which are the single largest and most relevant legislative actions to the concept of management corridors around NTSA routes. These concepts and clear statements of law in the NTSA remain law today and superseded many of the 1968 provisions that those seeking corridors and exclusions seek to have applied as if the laws were still in place. In a troubling turn of events, the 1983 amendments and FLPMA passage are not addressed in the Law[7] or Legislative history[8] sections of the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance at all, while minor revisions to the NTSA are discussed in some detail.

The 1983 NTSA amendments removed any basis for the principal of management of adjacent lands for the benefit of the route and replaced the adjacent lands concept with the following provisions:

“in selecting the rights-of-way full consideration shall be given to minimizing the adverse effects upon the adjacent landowner or user and his operation. Development and management of each segment of the National Trails System shall be designed to harmonize with and complement any established multiple-use plans for that specific area in order to insure continued maximum benefits from the land.”

In addition to clearly stating multiple use principals controlled NTSA routes and areas, Congress clarified the usages of NTSA designated routes by directly stating motorized usages in all forms were permitted by adding 16 USC 1246 (j). This provision states:

“Types of trail use allowed Potential trail uses allowed on designated components of the national trails system may include but are not limited to…the following: snowmobiling, …Vehicles which may be permitted on certain trails may include motorcycles, bicycles, four-wheel drive or all-terrain off-road vehicles.”

Rather than addressing these clearly stated uses of an NTSA area and applied FLPMA management standards to NTSA areas, the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance consistently relies on the artificially created versions of the NTSA to support exclusionary corridors being recommended. The Organizations are unable to determine the basis for such a decision as the 2016 USFS Guidance and the clear language of the 1983 amendments directly conflict. In this situation, federal law clearly and directly controls and minimizing impacts and maximizing values for all interests cannot be achieved with implementation of a mile-wide corridor excluding most usages.

1d. The scope of USFS NTSA guidance is artificially limited to support management that conflicts with NTSA provisions.

The 2016 USFS CDT Guidance systemically provides partial summaries of the NTSA provisions that simply do not reflect the entire provision being cited for the basis for the management decision and further relies on numerous legislative reports that are simply not available. While some NTSA provisions are sometimes directly contradictory in identifying usages, USFS Guidance should be reflecting this conflicting guidance for managers to understand in the implementation process. Rather than reflecting this conflict, the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance chooses one usage and crafts guidance language in furtherance of that interest without mention of the conflict and seeking to rely on supporting documentation that may not even exist. While non-existent documents are relied on, the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance simply ignores other easily accessible guidance from Congress. The end result of this guidance document is that forest staff will be lead to a single conclusion for management of both National Trails System routes and corridors and this single conclusion directly conflicts with the direct language of the NTSA.

This conflict is exemplified Page 6 of 2016 USFS CDT Guidance which states as follows:

“Sec. 7(c): The use of motor vehicles along any national scenic trail shall be prohibited…but limited motorized use may be allowed to: meet emergencies, provide landowner access, provide for motor vehicle crossings.”

Clearly a blanket prohibition as recommended would immediately conflict with federal laws requiring that an NTSA designation benefit all users of the area. The Organizations do not contest these words are present in §7c of the NTSA but §7c continues with extensive guidance regarding multiple uses on the CDT as follows:

“Other uses along the historic trails and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, which will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the trail, and which, at the time of designation, are allowed by administrative regulations, including the use of motorized vehicles, shall be permitted by the Secretary charged with the administration of the trail”[9]

The Organizations vigorously assert that any USFS guidance should not be placing one of the conflicting usages above another in a manner that directly conflicts with clearly stated guidance from Congress but rather should be identifying the conflict clearly and then assisting managers in resolving this conflict in a manner that addresses the clearly stated intent of Congress, which is the NTSA was intended to benefit all activity. Again, this situation must be reviewed and corrected.

1f. Accurate summaries of NTSA plan provisions often simply omitted from Guidance.

In addition to failing to accurately summarize conflicting provisions of the NTSA, the 2016 USFS CDT guidance fails to accurately summarize USFS planning documents that clearly were available when the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance was prepared. Again, the specific interests of some users are elevated and an inaccurate summary of Trail specific documents is provided in the Guidance. This is exemplified on Page 2 of the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance which states:

“Motorized vehicle use by the general public is prohibited on the CDT, unless such use is consistent with the applicable policy set forth in the Comprehensive Plan.”

This simply is not accurate as the NTSA clearly states that forest planning goals and objective control lands in the Corridor and that travel management decisions control lands in the corridor.[10] In addition to these provisions, the 2009 CDT Plan provides pages of management decisions regarding placement of the trail foot prints and proper management of the CDT in areas where other uses predate the development of the CDT. This simply is never mentioned in the 2016 USFS CDT guidance.

The 2009 CDT plan also provides high quality information regarding levels of usage that the 2016 USFS CDT guidance appears to assert are prohibited. A meaningful and complete review of the CDT plan reveals it clearly states:

“(2) At the time the Study Report was completed (1976), it was estimated that approximately 424 miles (14 percent) of existing primitive roads would be included in the proposed CDNST alignment.”[11]

In addition to the 14% of the CDT that is a motorized road, there are extensive but unspecified portions of the CDT located on motorized trails and significant portions of the CDT are groomed by the motorized community to access backcountry recreational areas for decades. This simply cannot be reconciled with exclusionary corridors.

It is significant to note that Continental Divide Trail (“CDT”) plan has adopted a blanket recognition of relevant travel management of areas around the CDT in its management plan. The 2009 CDT Plan provisions are as follows:

“Motor vehicle use by the general public is prohibited on the CDNST, unless that use is consistent with the applicable land management plan and……. (5) Is designated in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart B, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and:

(a) The vehicle class and width were allowed on that segment of the CDNST prior to November 10, 1978, and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST or

(b) That segment of the CDNST was constructed as a road prior to November 10, 1978; or

(6) In the case of over-snow vehicles, is allowed in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart C, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST.”[12]

Given the fact that the CDT plan specifically states the need to recognize travel management as the controlling factor for use of the trail tread and adjacent corridors in a manner consistent with multiple use requirements, the Organizations vigorously assert that these portions of the CDT plan would be rendered irrelevant with the designation of exclusionary corridors. This is a direct indication there is a problem with the corridor concept being recommended.

The failure to accurately review all relevant decision documents is even more problematic when site specific Congressional action on a particular trail is brought into the discussion. While our Organizations do not have guidance documents regarding the PCT, these concerns regarding this type of conflict are highlighted on the PCT. Congress has specifically identified crossing points that are to be reopened on the PCT as exemplified by the designation of two crossing locations on the Bridgeport Ranger District of the Humbolt-Toiyabe NF.[13] Again the Organizations must express serious concerns about any landscape level guidance documents for a NTSA route excluding motorized usage that brought management into clear conflict with these Congressional actions and related planning efforts.

1g. Significant alterations of any NTSA location require Congressional approval.

Throughout the 2016 USFS CDT Guidance, the concept of managers simply moving uses on and off the CDT by changing route location is embraced. The NTSA also provides guidance on the large-scale relocation of any Congressionally designated scenic trail from its original location as the NTSA continues as follows:

“relocation of a segment of national, scenic or historic trail….A substantial relocation of the rights of way for such a trail shall be by Act of Congress.” [14]

While Congress was clear on the desire to retain authority over the alteration of any National Trail, the failure to define “significant” places any changes in a national scenic trail from its original location, in the case of the CDT the 1977 report to Congress outlining its location, on questionable legal basis.

The Organizations are again concerned regarding the basis for this management guidance as no provisions are made for addressing these long-term impacts of numerous site-specific changes of Congressionally approved routes is provided. This is again a concern as Congress specifically and clearly retained the authority to approve but no methodology is provided for in guidance to provide for such a review.

1h. Economics and equity must be addressed in NTSA area management by Congressional declaration and Executive Order.

While the NTSA guidance fails to provide accurate guidance on numerous issues identified above, the NTSA guidance is clear on issues involving equity and usage of NTSA routes and the need to balance multiple usage based on these factors. On these issues, there is a huge amount of consensus between the Executive Orders of both Presidents Obama (EO 13553 of 2011) and President Trump (EO 13771 of 2017) and the provisions of the NTSA, which provide as follows:

“(9) the relative uses of the lands involved, including: the number of anticipated visitor-days for the entire length of, as well as for segments of, such trail; the number of months which such trail, or segments thereof, will be open for recreation purposes; the economic and social benefits which might accrue from alternate land uses; and the estimated man-years of civilian employment and expenditures expected for the purposes of maintenance, supervision, and regulation of such trail;”[15]

Clearly this balancing of competing economic and social benefits cannot be furthered with the recommended management standards as these guidance documents have already decided the balance is in favor of certain users and not others. While there is a huge level of consensus across political parties and government branches on the need for a cost benefit analysis of management decisions and equity in these management decisions around NTSA designations, these issues simply are not addressed in 2016 USFS CDT guidance. This concern is highly relevant as the CDT is traversed by dozens of visitors per year[16] and only hundreds traverse the entirety of the PCT per year[17]. The lack of equity in requiring landscape level exclusionary corridors for the management of dozens of users per year is immediately apparent. Cleary this is an issue where guidance should be provided and has not been raised due to the immediate conflict that will result, as this type of analysis would contradict the recommended exclusionary corridors.

Given the systemic protection of multiple uses on NTSA routes and repeated opportunity Congress has had to require exclusionary corridors and exclusion of multiple from NTSA routes, it must not be overlooked that the Congressional actions have consistently protected multiple uses with stronger and stronger standards and requirements in the law. This action in federal law prohibits the implementation of any landscape closures of an NTSA route or area and as a result the Organizations are opposed to any alternative being developed that would bring such a concept forward as such a concept is no more acceptable than a forest recommending motorized trail usage in a Wilderness area.

2a. Financially sustainable recreational opportunities must be required in the RMP.

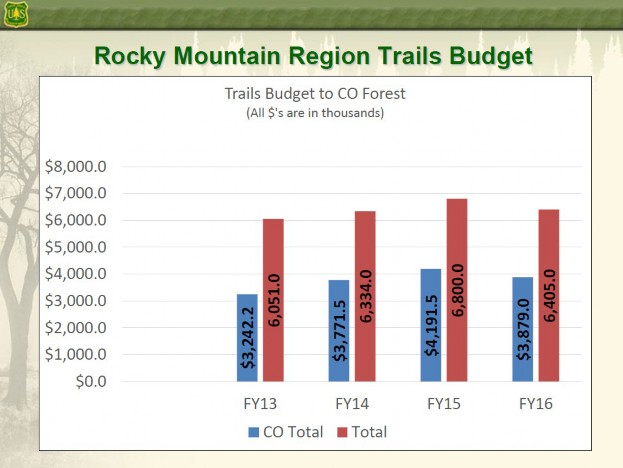

After reviewing the recreational assessment for the Proposal, the Organizations were thrilled that GMUG managers were seeking to proactively address expansion of recreational opportunities in areas where it was appropriate. The Organizations vigorously support the expansion of recreational opportunities on public lands, but such a position is not without limit. The Organizations submit that financial sustainability of any new routes must also be clearly addressed in the expansion of any recreational opportunities, as there is a very limited amount of funding for trail development and maintenance. The Organizations have provided detailed input previously regarding the benefits of the State OHV trails program to land managers, but other groups simply have failed to step up to this level. While the OHV and OSV program is vigorous in Colorado, it is also not enough and land managers partner with the funding from the state to make much of this effective and the Organizations would be very concerned with the large-scale expansion of projects that did not address the ongoing need for maintenance and upkeep of facilities as these partnerships currently in place would be put at risk.

When other trail uses are expanded without specific funding sources and a hard look at resources available to support the long-term success of the project, existing partnerships are strained and resources are stretched beyond capacity for maintenance. This is simply unfair and undermines the partnerships that the motorized community has worked hard to establish. Simply accepting a group assertion that trails can be maintained is not enough and land managers must take a hard look at the capacity to maintain new routes with existing resources. Often managers are asked to move forward with expansions of trails by hundreds of miles for a small user group when that user group is asserting maintenance of these networks can be achieved with a trailer, some hand tools and volunteers. Everyone knows that simply is not possible. Concerns on this type of maintenance are expanded when the fact that many of these groups are asserting this type of maintenance is available on trails across management boundaries or at the landscape level. Often trail advocates are asserting to be able to maintain routes on several forests, field offices and local municipal areas at the same time and often the track record for this type of maintenance is marginal at best.

Such a position also fails to recognize that much of the maintenance necessary may be occurring at trailheads and parking lots with the ongoing need to maintain toilets and trash bins and grading the parking areas and access roads. These are projects that simply cannot be undertaken with hand tools. The lack of factual sustainability of such a position is further evidenced by the fact that the single largest challenge often facing recreation managers working on trails on the GMUG is the large amounts of dead trees that can rapidly obstruct a route under normal conditions. These obstructions can become much worse with even a minor weather event and pose a costly issue for maintenance. We have enclosed a copy of our comments on the Plunge Project[18] outside Palisade Colorado as an example of the type of project that would evidence why we are raising this issue in the comments as this proposal is steep, remote, and on highly erosive soils and is crossing jurisdictional boundaries. This is a good example of the projects that must be approached with high levels of caution and could easily put the strong partnerships at risk of failure in the long term on the GMUG.

2b. Colorado recreational trends should be recognized and Forest level experiences with recreational visitation must be relied on.

In the recreational assessment, significant amounts of data from national trends and analysis in recreation are solely relied on for establishing trends in recreational usage. While we understand that exact recreational visitation may be difficult to obtain, relying solely on national data and trends is problematic as it overlooks the fact that visitation to recreational facilities in Colorado is growing across all interests and concerns due to the fact that the Colorado population is explosively growing. As a result, the Organizations would be concerned about any planning assumptions on the GMUG that expected visitation for any recreational activity to go down.

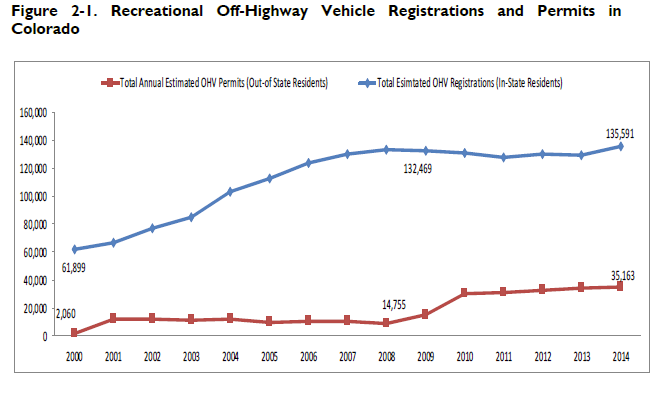

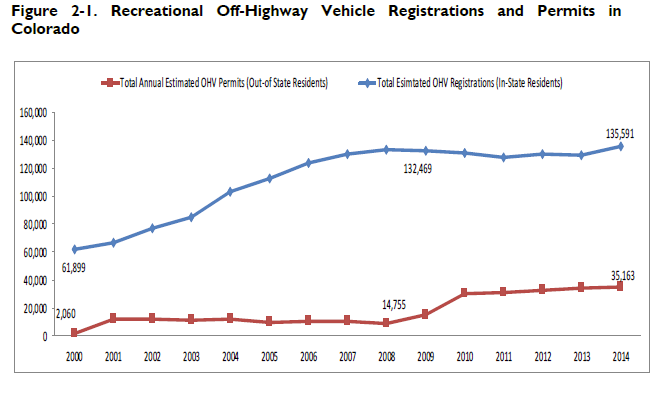

The Organizations would note that while some actions may have seen declines in participation at the national level, the Organization would be hard pressed to identify any activity that is declining in visitation in Colorado. As more specifically identified below, both OHV and OSV registrations with the State of Colorado have seen consistent increases over the last decade as reflected in the following charts from Colorado Parks and Wildlife regarding the steadily growing demand for registration of these vehicles.

The Organizations would note that such a recognition of the consistent growth of state registrations is important given the fact that OSV travel is thought to be declining in visitation and other usages are thought to be explosively growing based on the Cordell national study. [19] The Organizations experiences with outdoor recreation in general, the demand for all recreational opportunities and visitation to Colorado public lands has been explosively growing across all user groups, which directly contradicts the information provided by the Cordell study regarding national demand for particular opportunities. The Organizations would note that such a decline in OSV recreation would not be supported by Colorado Snowmobile registration numbers, which CPW recognizes have held pretty steady in the last decade. Our experiences are that most winter trailheads visitation is at levels we have never experienced before, as the Grand Mesa area is rapidly becoming a national destination for OSV recreation and more and more people are visiting Colorado from further and further away. Similar experiences can be seen regarding the explosive growth in demand for recreational opportunities on the GMUG over the last decade.

We would also note that many areas of the country experienced marginal snow years around 2010 and as a result many snowmobiles in extensive regions of the country never even got registered due to the lack of snow. Again, this was not the experience in Colorado as some of these years were well above average in terms of snowfall and visitation. While light registrations of OSV in NY or Vermont due to limited snowfall may be an interesting topic for discussion nationally, this issue is simply not relevant as a planning tool for the GMUG. As an industry or national trend, the mountain snowmobiling experience is now the most sought-after snowmobile experience in the nation and the GMUG has rapidly become a national destination for those seeking the mountain riding experience.

The Organizations are also concerned that throughout the recreational assessment the use of percentages of changes in visitation are often relied on for analysis. This is problematic as many of the interests that are reflected in the assessment are exceptionally small user groups, such as exemplified by mountain climbers. While mountain climbing is clearly a planning interest for the GMUG, this is a relatively small user group overall and a 100% increase in demand for these opportunities may only draw a small number of actual people to the GMUG. By Comparison, many large groups of visitors, such as camping or OHV, may see small percentages of growth nationally, but these are large groups to start with and as a result a small percentage of change in these groups may result in huge planning concerns for the GMUG as thousands of people may be represented in that small percentage of change in visitation.

The Organizations are very concerned that in the discussions around the winter recreational opportunities that is provided in the recreation assessment there is no mention of the importance that winter grooming plays in providing basic access to winter recreational opportunities on the GMUG. As a result, a critical factor in this opportunity comparison is missed, mainly that any recreational access is provided as a result of the OSV registration and grooming program in place on the forest and this grooming program has been a critical factor in the winter trail network developing in the manner that it has.

3. Reopening of the Alpine Tunnel historic district to all forms of motorized recreation

The Organizations would suggest goal and objective to restore access to the Alpine Historic District for all forms of travel as a goal in RMP. General public access to the area has been blocked by the natural deterioration of the road in spots, which could be easily repaired but access was more immediately challenged by more extensive damage to the roadway as a result of a winter avalanche. While this could be repaired, it is a more significant undertaking. This area is hugely unique and valuable recreational opportunity and experience to the public, especially with detailed historical information that is available to further expand the public understanding around the unique nature and history for the areas.[20] The Organizations would like to see restoring access to these unique recreational opportunities identified as a management priority in the RMP.

3a. Lynx Management standards in the Proposal directly conflict with best available science and USFS guidelines on the issue.

The Organizations are deeply troubled that the Proposal is carrying forward many of the outdated and superseded management standards that have plagued Lynx management for decades and have been specifically debunked. The continued reliance on this information is highly frustrating to the Colorado motorized community as we have been directly supporting lynx research throughout the region for almost a decade in an effort to develop best available science. This has included the direct funding of lynx and wolverine research conducted by John Squires and his team in partnership with the Idaho Snowmobile Association and the logistical support for lynx research efforts of the Rocky Mountain Research Station with Liz Roberts on both the White River and San Juan national forests seeking to better understand the response of lynx to higher levels of recreational activity. CSA attempted to donate a snowmobile to researchers but was not successful as the unit needed to be returned to the association after completion of research. Despite this setback the Association was able to provide significant amounts of fuel, oil on the ground knowledge and numerous recovery efforts for snowmobiles used by researchers that became stuck in the backcountry with CSA grooming equipment over several years.

While the 2013 Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy is mentioned in the index of the terrestrial species assessment the application of standards in the assessment is completely inaccurate and reflects more of review is of information that has been superseded than up to date information. The conflict between standards applied in the Species Assessment and the 2013 LCAS is stark when comparisons are made. The assessment specifically provides as follows:

“Road, trail and recreational activities that results in snow compaction may facilitate increased access into lynx habitat and competition for food resources by competitors (primarily coyotes). Over-the-snow vehicle use and additional modes of winter recreation are anticipated to increase on the GMUG National Forests.” [21]

The Organizations wanted to highlight some of the more significant changes in lynx management standards in the 2013 LCAS including:

- Recreational usage of lynx habitat is a second level threat and not likely to have substantial effects on the lynx or its habitat. Previous theory and management analysis had placed a much higher level of concern on recreational usage of lynx habitat; [22]

- Lynx have been known to incorporate smaller ski resorts within their home ranges but may not utilize the large resorts. Dispersed motorized recreational usage certainly does not create impacts that can be equated to even a small ski area; [23]

- Road and trail density does not impact the quality of an area as lynx habitat;[24]

- There is no information to suggest that trails have a negative impact on lynx; [25]

- Snow compaction from winter recreational activity is not likely to change the competitive advantage of the lynx and other predators;[26]

- Snow compaction in the Southern Rocky Mountain region is frequently a result of natural process and not recreational usage; [27]

- Winter recreational usage of lynx habitat should only be “considered” in planning and should not be precluded given the minimal threat this usage poses to the lynx; and [28]

- Failing to manage habitat areas to mitigate impacts of poor forest health issues, such as the spruce and mtn pine beetle, is a major concern in lynx habitat for a long duration.[29]

The Organizations are aware that the 2013 LCAS represents a significant change in management standards for a wide range of issues from the 2000 LCAS and Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment. It is our intent in providing a copy of the 2013 LCAS at this time that complete incorporation of this best available science, which reflects the minimal impacts of recreational usage of lynx habitat will streamline any site-specific planning issues in the future.

The fact that snow compaction is a natural force across the globe is addressed in significantly more detail in other parts of these comments.

4. Recreation Economics

The Organizations would like to provide new additional information regarding the importance of multiple use recreational access and related benefits to communities relying on recreational activity to provide critically needed tax revenue. The Organizations are aware that many counties in the vicinity have moved away from the dark economic times that plagued them several years ago, as exemplified by Summit County Colorado identification as number 3 on the Wall Street Journal list of 21st Century Ghost Towns.[30] Unfortunately, many communities outside the direct influence of ski area-based revenue continue to struggle and overly rely on recreational opportunities to provide basic services to residents. Many of these communities might include Paonia, Almont or Marble as examples. Given the importance of recreation to these communities and many of our members that live in these communities, the Organizations believe a brief update of the economic impacts to these communities that resulted from the Proposal is warranted.

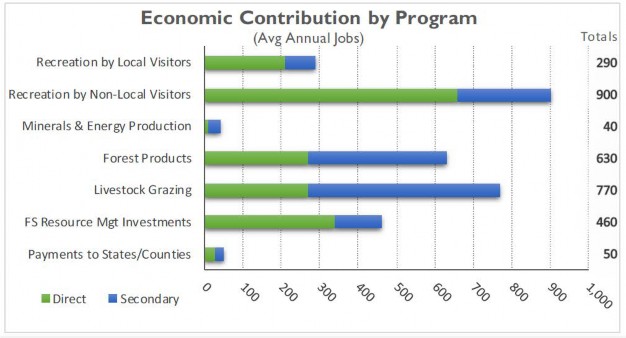

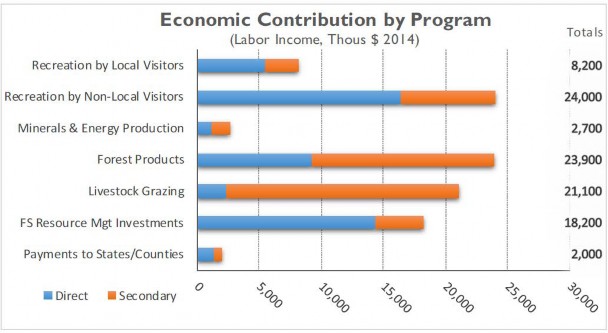

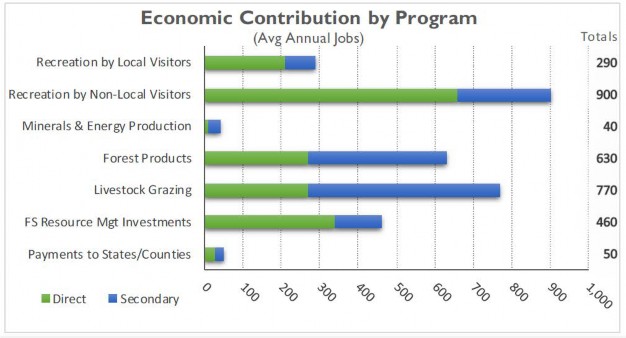

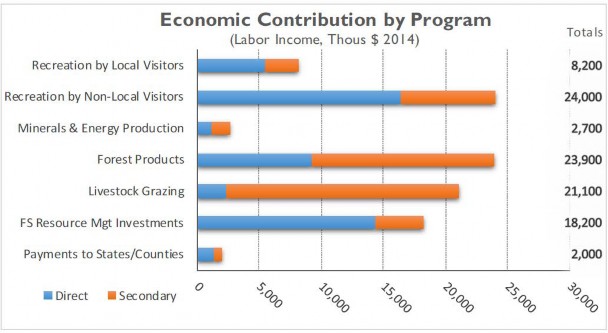

The first piece of new scientific research is the local economic information from USFS, as part of their “at a glance” summaries for the GMUG National Forest, which identifies the overwhelming importance that recreation plays in the success of local communities both in terms of revenue to local communities but also direct employment. The USFS summarizes their conclusions in the following graphs[31]:

It is difficult to understate the importance of the economic contribution of recreational activity and other activities that would be prohibited in the Proposal to local communities when the USFS estimates that the economic benefits of these activities outpace all other.

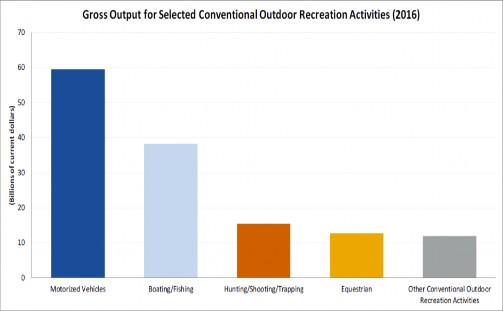

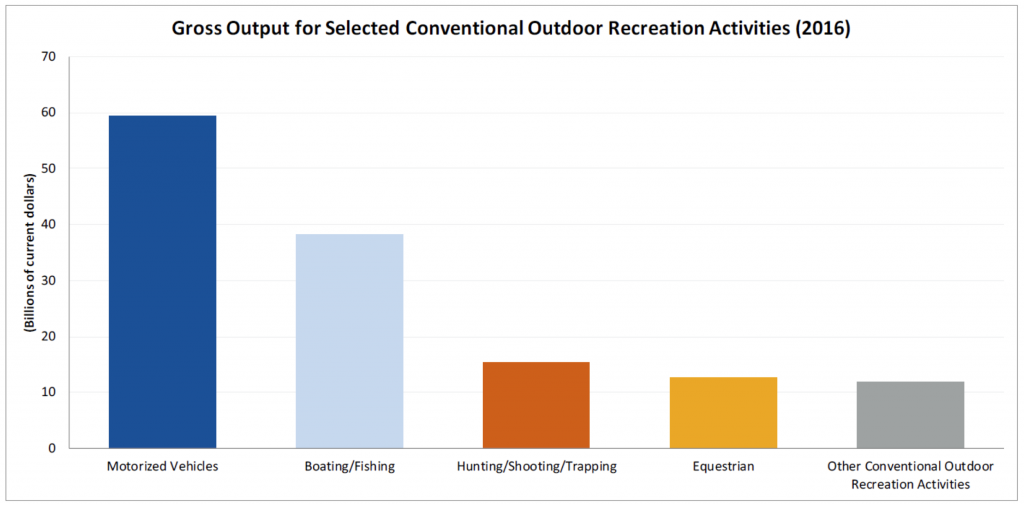

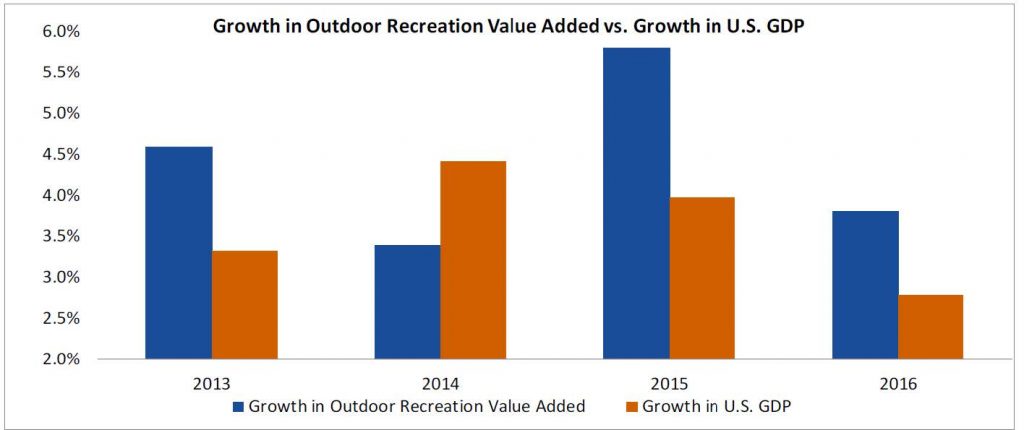

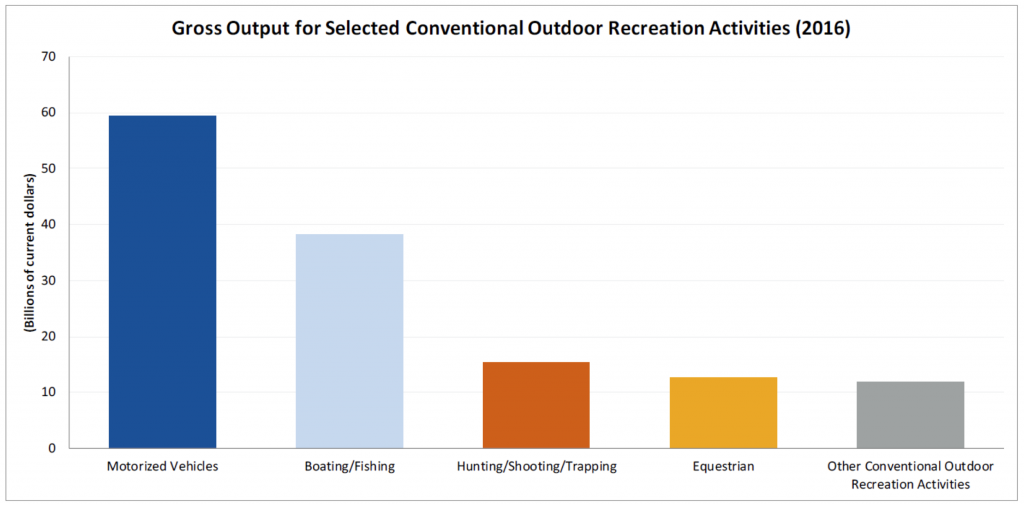

New research highlighting the economic importance of multiple use recreation to the recreational spending benefits flowing to local communities comes from research from the Department of Commerce. This analysis was prepared at the request of Department of Interior Secretary Sally Jewel in 2012, addressing the importance of recreational spending in the Gross Domestic Product as recreational spending accounts for more than 2% of the GDP.[32] This research clearly identified the important role that motorized access plays in recreational spending, which is summarized in the following chart:

This research concludes that motorized recreation outpaces the economic contribution of boating and fishing at almost twice the rate and that motorized recreation almost outspends all other categories of recreation combined. Given that motorized usage plays major roles in both the hunting and fishing economic analysis, the three largest components of economic benefit from recreational activity would be prohibited when multiple use recreational access is lost in any area. As a result of the overwhelming nature of these conclusions, the Organizations have to express serious concerns when the lion’s share of economic drivers are excluded from using any portion of public lands as clearly economic benefits are limited. The negative economic impact concerns regarding degrading multiple use access are immediately apparent.

The risk of negative economic impacts is also highlighted in newly released research from the US Forest Service, which estimates that recreation on National Forest Service Lands accounts for more than $13.6 billion in spending annually.[33] Experts estimate that recreational spending related to Wilderness areas accounts for only 5% of that total spending or approximately $700,000 million nationally. [34] The limited economic driver of Wilderness based recreation is compounded by the fact that more than 20% of the trail network that is currently located on USFS lands is within Wilderness areas. Again, this type of underutilization of any recreational resource is concerning to the Organizations simply because of the allocation of the resources and funding and weighs heavily against expansion of any recommended Wilderness or other exclusionary designations in the planning process. As we have previously notes, those types of designations are some of the most underutilized areas in Colorado for recreational activity.

The basis for the disparate economic benefits from recreational resources is easily identifiable when USFS comparisons for economic activity of recreational users is compared in the research below: [35]

We will not be addressing this research at length as we have included this analysis in our previous comments other than to note the conclusions of this research are consistent with conclusions that high spending user groups, such as snowmobile and OHV users are consistently excluded, while low spending groups such as cross-country skiers and hiker are permitted in many restricted or limited access management areas. Given the fact that low spending profile users are often spending only 20% of higher spending profile groups, these conclusions are consistent with the conclusions of both the Department of Commerce and new USFS research.

While the imbalance in spending profiles is problematic, the fact that once Wilderness is designated the general public fails to use the limited recreational opportunities in these areas is even more concerning. Nationally, congressionally designated Wilderness accounts for approximately 19% of USFS lands but results in only 3.4% of all visitor days.[36] In the State of Colorado, there is approximately 22% of USFS lands managed as Wilderness[37] but despite the expanded opportunity results in only 3.7% of visitor days on the GMUG National Forest.[38] As we have noted in previous comments there are significant declines over time in the visitation to and demand for Wilderness based recreational experiences. Given the significant underutilization of Wilderness resources in the area of the Proposal, the Organizations must vigorously assert that any economic risk is significantly negative and must be addressed or at least recognized by the communities in the vicinity of the Proposal areas.

As we have previously noted in greater detail in previous comments, motorized recreation provided $2.2 billion dollars to the Colorado economy and accounted for more than 15,000 jobs in 2014. A copy of the complete COHVCO study that is the basis for this information has been provided with previous input from the Organizations.

5a. Many of the areas found to be suitable for recommended Wilderness designation have been previously found unsuitable for designation by Congress.

Prior to addressing the specific and extensive history of areas on the GMUG of areas being reviewed by Congress and found unsuitable for designation as Wilderness, the Organizations must address two significant landscape level concerns that have arisen around many of the recommended Wilderness areas from the 2007 draft RMP. Our first landscape level concern involves the relationship of the site-specific inventory of much of the GMUG by Congress and specific release of many areas from further review for possible designation as Wilderness in the future by Congress. This release of areas by Congress from future designation greatly outweighs the fact that there may be legislation now before Congress on this issue in the form of a citizen-based Wilderness proposal. The Organizations are aware there is great pressure to recognize these legislative drafts that have been before Congress sometimes for decades but the Organizations must note that the decision NOT to list these areas as Wilderness that actually passed Congress and became law must be properly weighted again the existence of a legislative proposal that has not passed either house of Congress and often completely lacks even a sponsor in the House of Representatives. Any argument that a stalled legislative proposal should carry more weight than a site-specific analysis and decision that has actually passed Congress regarding the ineligibility of the area for future designation is probably lacking legal and factual basis. The Organizations comments on both legislative proposals is attached to these comments as Exhibit 3. The Organizations submit that many of the citizen Wilderness proposals that are currently addressing GMUG lands are not moving because they are simply badly out of balance and would designate Wilderness in areas that were released in previous Wilderness legislation.

Here a comparison of weighting proposed legislation at a higher level than current federal law is valuable and will provide more clarity to why we are asserting the mere proposal of Wilderness on the GMUG is not a management or analysis issue for planners. This comparison involves mountain bike usage in Wilderness areas. Similar to the San Juan and Continental Divide legislation now before the US Senate, there was also draft legislation in the 115th Congress to allow mountain bikes in Wilderness (HR 1349) that actually moved out of the House committee hearing on the issue. After passing committee, HR 1349 moved no further in the House and failed to obtain any Senate sponsors. Clearly this type of legislation could not be applied by land managers in the planning process to allow mountain bikes in Wilderness areas, as it directly contradicts federal law despite the draft Legislation being proposed. Congress has spoken on this issue and there is no basis to overturn that position without further action actually passing Congress. The Organizations believe the basis for the two decisions by land managers must be consistently applied, and there should be no mountain bikes in Wilderness due to the conflict with federal law and no recommendation of Wilderness designations in planning efforts for GMUG areas already repeatedly addressed by Congress and found unsuitable and released back to multiple use. Each is a direct violation of federal law, despite what has been asserted by those advocating for more Wilderness. Existing federal law must outweigh proposed legislation in the planning process.

The history of both the Continental Divide Proposal, and earlier versions of this legislation that trace back to the original Hidden Gems Proposal and San Juan Wilderness Proposals by Senator Bennett clearly shows the lack of support for the expanded designations across larger communities. Rather than being a basis for management of these areas as recommended Wilderness these proposals provide a concrete basis for management of these areas in compliance with existing federal law mandating multiple use. A brief history of the San Juan Wilderness Legislation reveals a long history of nonsupport for the proposal in Congress, as there has never been a house sponsor even named for the Proposal[39]. Even in the Senate, the proposal has moved to hearings on several occasions and while it has gotten out of committee, the larger Senate has never even voted on this Proposal. This is a strong indication of the LACK of support for the Proposal. Even more troubling is the fact that the San Juan Legislation has not even been introduced in the Senate since 2013. The Organizations submit that the 5-year hiatus for the legislation speaks volumes to the true amount of support for the Legislation.

The Legislative history of the Continental Divide Legislation provides no basis for management decision as this Proposal has been submitted in various forms for almost a decade and has also not moved beyond committee hearing, and many years has been unable to even get a hearing. This Legislation was originally proposed in Congress in 2010 with claims of broad support and extensive vetting of the Proposal through the Hidden Gems based discussions. Vetting of the proposal provided to be less than complete and many problems were immediately identified and as a result the Central Mountains version of Hidden Gems was reworked several times as exemplified by the Rocky Mountain Recreation and Wilderness Preservation Act of 2012[40]. This did little to build community support for the Proposal. Recently the legislative name was changed and minor changes to the proposal were undertaken, and this version again failed to move.

The Organizations would be remiss if the troubling legislative history of other proposals that have incorporated San Juan and Continental Divide boundaries was not addressed, such as Congresswoman Dianna DeGette’s Colorado Wilderness Act that was originally introduced in 1999 was not mentioned[41]. These Proposals have also failed to move beyond a committee hearing despite being introduced for almost two decades as well. As result, managers now have a clearly identified basis to not incorporate these legislative proposals into planning as there is clearly defined track record of minimal public support for the Proposals. The failure of these proposals in Congress simply does not create a valid basis for planning actions by Congress.

This lack of support for the San Juan and Continental Divide version of Hidden Gems, is further evidenced by the fact that while these proposals have languished in Congress for more than two decades in one form or another, other land use legislation including Wilderness designations has been developed and rapidly moved through Congress regarding Colorado public lands. This legislation would be the Hermosa Watershed Legislation of 2013, which was developed, passed into law and subsequent planning completed in a decade less time than San Juan and Continental Divide have been languishing in Congress without larger support. While the mandates of the Hermosa Watershed Legislation are not legally binding on the GMUG, the factual differences are highly relevant to the value of land management legislation that does not move. In 2013, the Hermosa Watershed Legislation[42] was not even a Legislative Proposal but this legislation was developed from the ground up, passed both houses of Congress and was signed by the President while other pieces of legislation remained stalled. [43] While the Hermosa Watershed Legislation does not impact GMUG planning the rapid movement of this legislation through Congress speaks volumes to the lack of support around the other pieces of Legislation that have been in existence for much longer and simply never moved. Their value in planning is marginal at best.

While USFS policy asserts that citizen Wilderness proposals be addressed in the planning process, the Organizations vigorously assert that the mere existence of a Proposal is not enough review for the planning process. The Organizations submit that the entirety of the history of these citizen Proposals must be reviewed in the planning process as many of the areas have been the basis of citizen Wilderness Proposals since 1980 as directly evidenced by the 1980 Colorado Wilderness act[44] when the boundaries of many of these areas were established and drawn to protect many of the same usages that remain in these areas to this day.

The second concern around citizen proposals for Wilderness is a policy concern and involves a consistent position taken by land managers that the public should work together attempt to bring solutions to issues to them. When land managers are recommending areas for possible designation that have been previously released by Congress, the managers are now working against the public collaborations that were the basis for the release of the area back to multiple use. If there is a consensus position regarding the management of areas that has been achieved and passed into law by Congress it should be enforced with regard to all interests, regardless of the position. Consensus positions should be supported and defended by land managers in Colorado as there has been a lot of balancing and collaboration that has gone into the Congressional action for management of public lands for decades. When land managers recommend Wilderness for areas that have been specifically inventoried by Congress and found ineligible, land managers are undermining a consensus position that was achieved. Despite insisting that collaborative efforts targeting consensus management are needed here, managers would be undermining the very consensus they seek to obtain by trying to recommend Wilderness in many areas on the GMUG. Additionally, recommending Wilderness based on these proposals would undermine the public process as the legislation is simply badly out of balance in terms of land use and as a result has little support from the general public.

5(a)(2). The extensive history of Congressional action addressing public lands on the GMUG must be addressed.

As we have noted, the legislative inaction around many of the citizen-based Wilderness proposals for lands under GMUG management must be addressed in decision making as well as each of these citizen proposals have a long and weak history of support in larger legislative efforts. The fact that some of these proposals have been in existence for almost 2 decades and are no close to passage now than when they started must be a factual concern in forest planning. While there is minimal support for many of these citizen proposals, there is a long and vigorous history of Congress specifically addressing management of public lands on the GMUG and being able to move land management legislation through Congress. It is troubling that many of the areas that have been specifically identified for multiple use management in order to develop a balanced land management bill that would move through Congress were recommended for Wilderness in the 2007 draft RMP for the GMUG. The Organizations submit this recommendation fails to account for previous Congressional actions regarding these areas and directly undermines the ability of balanced land management legislation to move at the landscape leve

The Organizations are very concerned regarding the overly narrow view of Wilderness inventory that is provided in the January 2018 Wilderness Inventory guidance on the Forest, as this document completely fails to address the extensive Congressional actions that have been taking regarding management of lands on the GMUG for Wilderness and other uses. The overly narrow scope of analysis in the inventory is reflected as follows:

“After applying the size and improvements criteria, the handbook directs the Responsible Official to review information provided through public participation during the assessment phase of the plan revision process, including areas that have been proposed for consideration as recommended wilderness through a previous planning process (i.e., the 2007 GMUG Proposed Plan), collaborative effort, or in pending legislation. With respect to areas proposed for consideration as recommended wilderness through collaborative efforts, two citizen proposals for wilderness and other special designations were submitted to the GMUG during the assessment phase. These proposals will be considered in combination with other public comments received throughout the GMUG wilderness process.” [45]

The Organizations would note that the compliance with federal law currently governing these areas may be implied in the above standards, it is not stated or otherwise addressed in the inventory documents currently available for public inspection. Given the repeated decisions of Congress specifically identifying areas on the GMUG for multiple use and unsuitable for designation as Wilderness the Organizations assert strict application of the above standard could easily result in an RMP recommendation that conflicts with federal laws specifically governing these areas. This must be avoided.

While addressing issues involving legislative history may seem unnecessary, it is important as many of the areas recommended for addition to the Wilderness system in the 2007 Draft RMP Proposal have been the basis of ongoing discussions for possible Wilderness designations since well before the Wilderness Act was originally passed in 1964. As a result, the lack of success around recent efforts to add these areas is important but also the history of not only each Wilderness areas that were designated and also areas that were not designated is important as A large portion of the areas recommended for Wilderness in the Draft 2007 RMP have been specifically reviewed and released from further management by Congressional action to be managed under non-Wilderness standards. In addition to the determinations of why these areas were found unsuitable for Congressional designation, these areas have been the basis of extensive inventory by the USGS and Bureau of Mines pursuant to §3b of the Wilderness Act as these were existing Primitive Areas when the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964. Given the specific review and release of many of these areas from further designation by Congress, the Organizations must question how the same areas could be recommended for Wilderness in the USFS planning process, despite what has been more than 50 years of review of possible basis for designation. Additionally, many of the areas were also found unsuitable still for even Roadless area upper tier areas under the Colorado Roadless Rule.

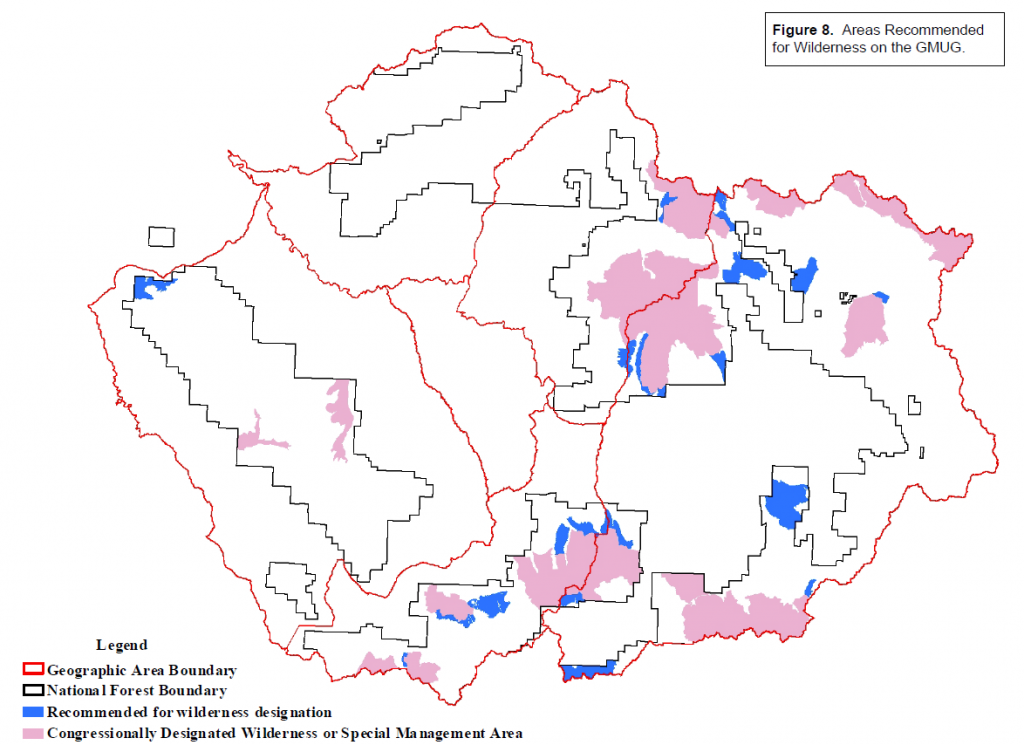

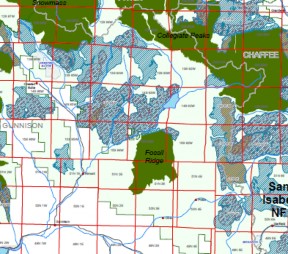

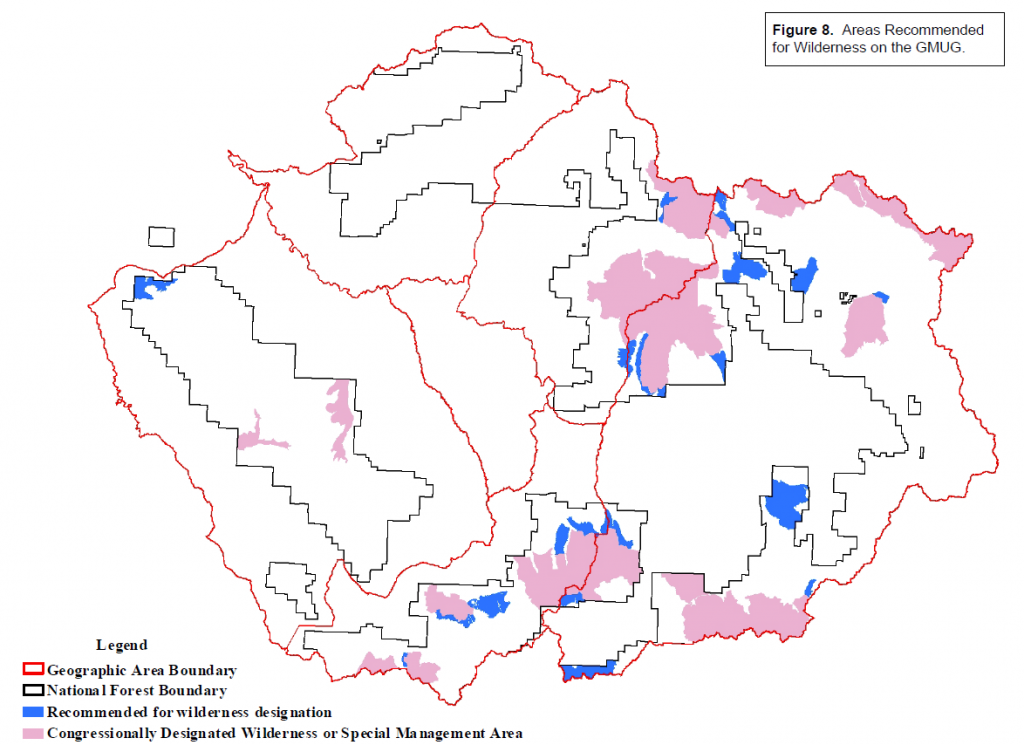

The 2007 Draft RMP provides the following map of recommended Wilderness:

These recommended Wilderness designations were applied despite the high levels of clarity around previous Congressional actions addressing public lands in GMUG planning areas. This clarity of Congressional action is exemplified in the 1980 Colorado Wilderness Act that created the Colligate Peaks, Raggeds and Fossil Ridge Wilderness areas. The 1980 Colorado Wilderness act specifically spoke of the need to protect multiple use in areas it was not designating as Wilderness as follows:

“SEC. 101. (a) The Congress finds that-

(1) many areas of undeveloped National Forest System lands in the State of Colorado possess outstanding natural characteristics which give them high values as wilderness and will, if properly preserved, contribute as an enduring resource of wilderness for the benefit of the American people;

(2) the Department of Agriculture’s second Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) of National Forest System lands in the State of Colorado and the related congressional review of such lands have identified areas which, on the basis of their landform, ecosystem, associated wildlife, and location, will help to fulfill the National Forest System’s share of a quality National Wilderness Preservation System; and

(3) the Department of Agriculture’s second Roadless Area Review and Evaluation of National Forest System lands in the State of Colorado and the related congressional review of such lands have also identified areas which do not possess outstanding wilderness attributes or which possess outstanding energy mineral, timber, grazing, dispersed recreation and other values and which should not now be designated as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System but should be available for nonwilderness multiple uses under the land management

planning process and other applicable laws……

(b)(2) The purposes of this title are to……. Insure that certain other National Forest System lands in the State of Colorado are available for non-wilderness multiple uses.” [46]

Additional clarity regarding the desire of Congress to return multiple use to areas that were not designated as Wilderness in the 1980 legislation is also provided by Section 107 of the 1980 Colorado Wilderness legislation, which clearly states as follows:

“(3) areas in the State of Colorado reviewed in such Act; for study by Congress or remaining in further planning upon enactment of this Act need not be managed for the purpose of protecting their suitability for wilderness designation pending revision of the initial plans; and”[47]

The scope of the areas that were inventoried is addressed with more detail in subsequent portions of these comments. Given the long history of clear Congressional action regarding the management of so much of the GMUG planning area, the Organizations must question what has changed in these areas and why would the previous consensus positions now need to be changed in terms of management of these areas. Clearly these previous Legislative actions developed high levels of public participation and consensus and should be honored. The fact that one group did not get exactly what they wanted in consensus efforts previously does not create the need for new consensus efforts without a serious change in the circumstances in the area. Also, recommendations of Wilderness in these areas must at least recognize the previous legislative determinations and explain why these determinations are not controlling for these areas any longer and why these areas may again be recommended for designation as Wilderness by Congress.

5a (3). Many of recommended Wilderness areas in the 2007 plan directly violate Federal law prohibiting buffer areas around many Wilderness areas on the GMUG.

As identified above there have been significant Congressional actions to address the management of many areas within the GMUG planning area for more than 50 years. The 1980 and 1993 Colorado Wilderness acts implemented additional protections for usages of areas outside the designated Wilderness areas with the addition of the “no buffer” concept to further protect multiple usage in boundary areas. The Organizations are aware that many of the additions of areas adjacent to existing Wilderness areas in citizen recommendations and proposals are based on the idea that such a boundary change would make preservation of Wilderness characteristics of the areas easier to manage. Asserting such a basis for management designation would be exactly the type of buffer that is specifically prohibited under the Colorado Wilderness Act and its amendments.

When implemented by Congress these “no buffer” protections were put in place to facilitate the consensus of multiple users and interests in these lands. The Organizations can see no reason why these consensus positions should be changed now as such a designation would be a direct violation of federal law specifically prohibiting the creation of buffer areas to protect wilderness areas that were designated. Congress has specifically reviewed these areas and determined where the boundaries should be located. Fossil Ridge, Colligate Peaks, Uncompahgre, Powderhorn and Raggeds Wilderness areas were created by the 1980 and 1993 Colorado Wilderness Act, and both of these pieces of legislation specifically required no buffer requirements as the 1993 Colorado Wilderness Act as follows:

“(e) BUFFER ZONES. —Congress does not intend that the designation by this Act of wilderness areas in the State of Colorado creates or implies the creation of protective perimeters or buffer zones around any wilderness area. The fact that nonwilderness activities or uses can be seen or heard from within a wilderness area shall not, of itself, preclude such activities or uses up to the boundary of the wilderness area.” [48]

While existing federal law, reflecting the consensus position that was reached in the 1980 and 1993 Wilderness Expansion Legislation, is exceptionally clear on the usages that are allowed outside these Wilderness areas. These pieces of federal law also clearly state that there shall NOT be any buffers around these new Wilderness areas, many citizen proposal and the 2007 draft RMP openly asserts that the basis for the designation of these areas is to provide a buffer for the Wilderness area. Such basis for designation would be a direct violation of federal law prohibiting management creation of buffers.

5b. A large portion of the GMUG has been inventoried as primitive area and released back to multiple use.

In addition to the extensive Congressional action specifically drawing many of the boundaries of Wilderness areas on the GMUG, Congress additionally reviewed the inventory of three primitive areas that were existing in the southern portions of the GMUG when the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964. These three primitive areas were identified as the Uncompahgre Primitive area, Uncompahgre Adjacent Primitive area and the Wilson Mtn Primitive areas. Again, when the 1980 Colorado Wilderness act was passed these inventories were reviewed for possible designations by Congress and areas that were found suitable for designation were designated as Wilderness and the primitive areas were abolished and returned to multiple use.

The 1980 Colorado Wilderness Act clearly abolished these areas from further possible management as Wilderness as follows:

“The previous classifications of the Uncompahgre Primitive areas and Wilson Mountain Primitive area are hereby abolished” [49

We have enclosed the complete inventory of each of these primitive areas as Exhibit 4 to allow planners to fully understand the detail and scope of these inventories and understand the scope of what was released by Congress and then recommended for Wilderness in the 2007 draft RMP. After a detailed review of these reports, it should be noted that many of the pre-existing usages that prohibited Congressional designation of these areas was recognized in these reports and inventory that began in the early 1970s. These usages and management challenges often remain in the areas that were recognized by the Department of Interior and Bureau of Mines, adding more credibility to the USFS inventories of these areas subsequently undertaken. Again, we simply cannot understand a fact pattern where Congress could specifically decline an area for designation as Wilderness and then land managers would again recommend the same areas for designation in the planning process. Such a position simply lacks rational basis in facts or law.

5c. Specific boundaries of the Uncompahgre (Big Blue) and Mt. Sneffels Wilderness were drawn with great detail by Congress.

In addition to the release of the large primitive areas that predated the 1964 Wilderness Act and comprised a large amount of the southern portions of the GMUG, the 1980 Colorado Wilderness act addressed the specific locations for the boundaries of both the Uncompahgre and Mount Sneffels Wilderness with unusually high levels of detail. The value of this level of detail should not be overlooked and again would draw any assertion of suitability for these areas as recommended Wilderness in the RMP into question.

Section 9 of the House Report issued for the 1980 Colorado Wilderness act provides a large amount of highly site-specific detail into the scope of analysis undertaken by Congress in developing this legislation and why boundaries are in the locations they are in. This bill memo provides:

“9. Lizard Head, Mount Sneffels, and Big Blue Wildernesses: These three separate wilderness proposals of 40,000, 16,200, and 100,000 acres, respectively, comprise what many feel is the most scenic and spectacular area in the entire State of Colorado, and is sometimes called the “Switzerland of America”. The area’s outstanding beauty and wild nature has been officially recognized since 1932 when the Wilson Mountains and Uncompahgre Primitive Areas were established by administrative regulation. In accordance with section 3 (b) of the Wilderness Act, the wilderness character of the two primitive areas was reviewed, and a wilderness recommendation on five separate tracts was forwarded to Congress in 197 4. The RARE II process resulted in further wilderness recommendations on lands contiguous to three of the five tracts. The Committee reviewed the Administration’s recommendations and determined that the 16,200-acre Mount Sneffels proposal was adequate to protect the highly scenic country north of Telluride. To the south-west, the Committee proposes a 40,000-acre Lizard Head Wilderness to link up the Administration’s Mount Wilson and Dolores Peak recommendations and include the headwaters of the Dolores River plus the landmark Lizard Head and Wilson Meadows. These additional lands largely lie within the existing Wilson Mountains Primitive Area and have important wildlife values as well as superlative wilderness qualities. The Committee, therefore, determined that wilderness should replace the current primitive area designation.

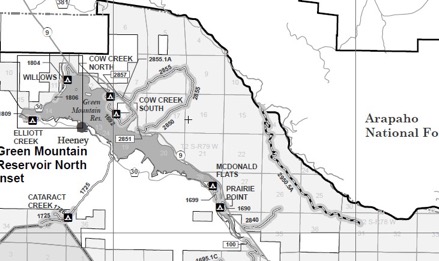

Similarly, the Committee recommends a 100,000-acre Big Blue Wilderness to join the Administration’s Big Blue and Courthouse Mountain proposals. The Committee additions include the heart of the eastern route of the Uncompahgre Primitive Area and such outstanding natural features as Matterhorn Peak, Wetterhorn Peak, Precipice Peak, Dunsinane Peak, Cow Creek and portions of the West, Middle and East Forks of the Cimarron River. The Committee feels the addition of these lands is vital to the overall integrity of any Big Blue Wilderness, and especially notes their outstanding scenic and watershed values. At the same time, the Committee recognizes that the public currently relies on motorized access to certain key areas, and therefore amended the bill to exclude lands in the vicinity of Nellie Creek and to excise two road corridors which extend part of the way up the Middle and West Fork Cimarron River drainages. Another boundary adjustment was made on the extreme western end of the area near Baldy Peak to exclude about 1,500 acres which are used by grazing permittees for frequent motorized access and intensive management activities associated with livestock grazing. The bill abolishes the Uncompahgre and Wilson Mountain Primitive Area designations for those residual Primitive Area lands lying outside the boundaries of the three proposed wildernesses. Most of these remaining lands are so interspersed with patented mining claims that their management as wilderness would prove infeasible.”

A complete copy of this House Report memo outlining the high levels of sight specific analysis that was undertaken by Congress is attached to these comments for your reference as Exhibit 5 to these comments. Given that many of the uses that Congress wanted to avoid impacting are still existing in these areas, the Organizations must ask why manager would ever want to violate the clear statements of Congress as to the location of these Wilderness boundaries.

When both the Mt Sneffels and Lizard Head Wilderness Areas were designated as Wilderness in 1980, the following provisions were included in the preamble of that legislation:

“(3) the Department of Agriculture’s second Roadless Area Review and Evaluation of National Forest System lands in the State of Colorado and the related congressional review of such lands have also identified areas which do not possess outstanding wilderness attributes or which possess outstanding energy, mineral, timber, grazing, dispersed recreation and other values and which should not now be designated as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System but should be available for nonwilderness multiple uses under the land management planning process and other applicable laws.”[50]

The Organizations must question why areas that have been specifically released by Congress for multiple use management and consistently found unsuitable for designation as Roadless areas would ever be found now available for Wilderness designation. The Congressional release of roadless areas, such as Sunshine, Wilson Mesa, Whitehouse and Liberty Bell is highly relevant due to the proximity of many of the new proposed Wilderness Area additions to both the Mt. Sneffels and Lizard Head Wilderness and that these areas were specifically excluded by Congress from Wilderness management previously.

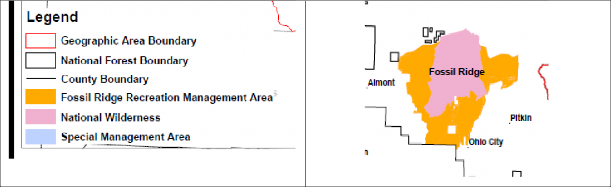

5c (2). Fossil Ridge Recreation Management area must be managed to protect management objectives set for the area by Congress.