Rio Grande National Forest Plan Revision

Rio Grande National Forest

Attn: Forest Plan Revision Team

1803 W. Highway 160

Monte Vista, Co 81144

LivRE: Rio Grande National Forest Plan Revision

Dear Supervisor Dallas:

Please accept these comments on the Rio Grande National Forest Plan Revision Project (“the Proposal”) on behalf of the Trails Preservation Alliance (“TPA”), Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) and the Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”). TPA, CSA and COHVCO vigorously support Alternative C of the Proposal due to this Alternative having the fewest categories for area management in the RMP, which we believe will greatly expand public understanding of the Proposal and provide significant long-term flexibility for the Rio Grande planning area moving forward. The flexibility of Alternative C of the Proposal is expanded by the fact that this Alternative provides the most flexibility for management moving forward as this provides the most multiple use opportunities. This expanded opportunity will allow for more site specific planning in the future, and the Organizations are aware that in site specific planning restricting access can be easily accomplished but amended a forest plan to expand opportunities has been almost impossible. Organizations are vigorously opposed to Alternative D due to its complexity and the fact that it functionally ties the hands of land managers dealing with the poor forest health that has become far too common in Colorado.

Prior to addressing our specific concerns on the Proposal, the Organizations believe a brief summary of each Organization is necessary to provide context to the comments. The TPA is a volunteer organization created to be a viable partner to public lands managers, working with the USFS and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding and multi-use recreation. The TPA acts as an advocate for the sport and takes the necessary action to insure that the USFS and BLM allocate a fair and equitable percentage of public lands access to diverse multi-use recreational opportunities. COHVCO is a grassroots advocacy organization representing approximately 230,000 registered off-highway vehicle (“OHV”) users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of multi-use and off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations. Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion as reflected by the more than 30,000 registered users in the State. CSA has become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling by working with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators. TPA, CSA and COHVCO are referred to collectively in this correspondence as “The Organizations.”

Prior to addressing the specific concerns regarding the development of the Rio Grande National Forest’s new Resource Management Plan (RMP), the Organizations would like to thank the Rio Grande National Forest staff for their efforts to date in the planning process. The Organizations are aware that the Rio Grande National Forest is one of the first forests to move forward under the new United States Forest Service (USFS) planning rule and at this time USFS guidance regarding the application of the new planning rule to local forests or planning units remains under development. This lack of planning rule clarity compounds the inherent conflict that exists between current forest planning timeline and the rate at which species management and research are progressing. This lack of clarity has made any efforts on the Rio Grande difficult at best as there are many new concepts and principals developed under the planning rule that will heavily impact plan development. The Organizations believe that the efforts to date have done a commendable job in satisfying these new requirements and standards and the Organizations remain willing to assist in resolution of any issues that might arise on this front in any way that we can.

1a. The reduced size of the Plan will build public support and result in a Plan that remains relevant and guides subsequent planning efforts.

The Organizations are supportive of the significant reduction in the overall size of the Proposal and reduction in the number of management categories in the Proposal, when compared to the current management Plan. This is an important step towards building public support and understanding for both the Plan and management efforts in the future. When any site specific has been undertaken under the current RMP, too often the public has simply been overwhelmed by the number of categories that are applied in the current RMP. The large number of planning categories is a barrier to public understanding of any planning efforts as most of the public do not have the time and resources to undertake even a basic review of the categories and how they are related to various aspects of any site specific plan or concern they may have. If the public is able to understand a plan they can support it. If an RMP is too large or complex, the public will oppose the plan, regardless of how effective the Plan may be or how the Plan supports or addresses any concern of that member of the public.

Often simple projects being undertaken in site specific planning, involve a large number of management categories in the planning area and each of these planning categories must be addressed in any site specific efforts to insure that the project conforms to each of these management standards. This is simply time consuming and expensive. A significant reduction in the number of management categories will streamline future site specific planning efforts and allow managers to address issues with what has consistently become a growingly smaller amount of resources.

1b. Overly specific plans result in significant additional costs over the life of the RMP and often result in standards that are a barrier to the forest addressing challenges on the ground.

The Organizations have also experienced the unintended consequences of an aging and overly specific forest plan when undertaking site specific planning. Any subsequent site specific planning ends up being very long and complex in order to address the numerous standards in the plan. This challenge is further compounded by the fact that often the basis and understanding for a particular standard are lost with the passage of time. As a result those undertaking site specific planning with an aging RMP are forced to develop overly specific analysis in their document as they are unable to understand the basis or concerns that a standard was to address. As a result, planners often end up analyzing every possible alternative or theory for a standard rather than being able to address relevant standards and avoid addressing standards that are unrelated to a particular project or issue.

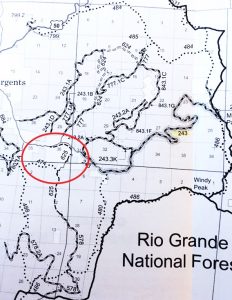

As Rio Grande planners are now painfully aware of as a result of the La Garita Timber sale efforts, overly specific analysis in a forest plan can become a serious barrier to addressing significant challenges on the Forest such as the Mountain Pine Beetle and Spruce Beetle outbreak. Too often areas were found to be unsuitable for timber harvest or managed for uses often unrelated to forest health and have included standards such as 15% treatment limitations in certain management areas. [1] After a review of the RMP, absolutely no basis is provided for how the 15% treatment ceiling was developed or what management issue the 15% standard was thought to be addressing. The Organizations submit that these are exactly the types of standards that should be addressed in site specific planning and represent standards that should be removed, if possible, from the new RMP. The insertion of standards that can’t be explained does not streamline planning and more efficiently use resources, but rather ties the hands of managers and provide a significant barrier to public understanding.

In addition to merely requiring more paperwork, any overly specific standards on issues that really are not suitable for inclusion in landscape level planning have placed a significant strain on the budgets of land managers, which have significantly constricted since the 1990’s. The Organizations do not anticipate a significant change in this long term funding trend and as a result future managers will be forced to undertake similar levels of management with lower levels of funding that ever before. While this is unfortunate, there is simply no basis to believe this will alter over the life of the next RMP. A streamlined and efficient planning document would ease this burden and allow limited resources to be directed to on the ground issues.

1c. Landscape level planning should address landscape level issues to insure the RMP remains relevant over its life.

Again the Organizations are thrilled that the Rio Grande NF is moving forward with the development of landscape level standards that are related to landscape level challenges in their planning efforts. This will significantly impact both the total number of categories and specificity of each category, and this will have an important long term benefit, mainly the RMP will simply remain more relevant to the management of the forest over the plans life and will result in site specific efforts undertaken in the future that are more streamlined as well.

The Organizations have been involved in numerous site specific efforts with the Rio Grande staff and it has been our experience that the RMP being replaced was more of a barrier to projects towards the end of its life than a document that really provided relevant guidance for site specific efforts. This was problematic at best and resolving these issues in site specific planning was often complicated by the fact that the reasoning for many of the specific standards in the outgoing RMP were simply unclear or had been entirely forgotten. This simply generated more paperwork and efforts in site specific efforts, as planners felt the need to address every variable that could have contributed to the standard being in the plan in order to make the site specific plan defensible if it was challenged. With a reduced number of categories, site specific planning should be able to become more streamlined and efficient in the future.

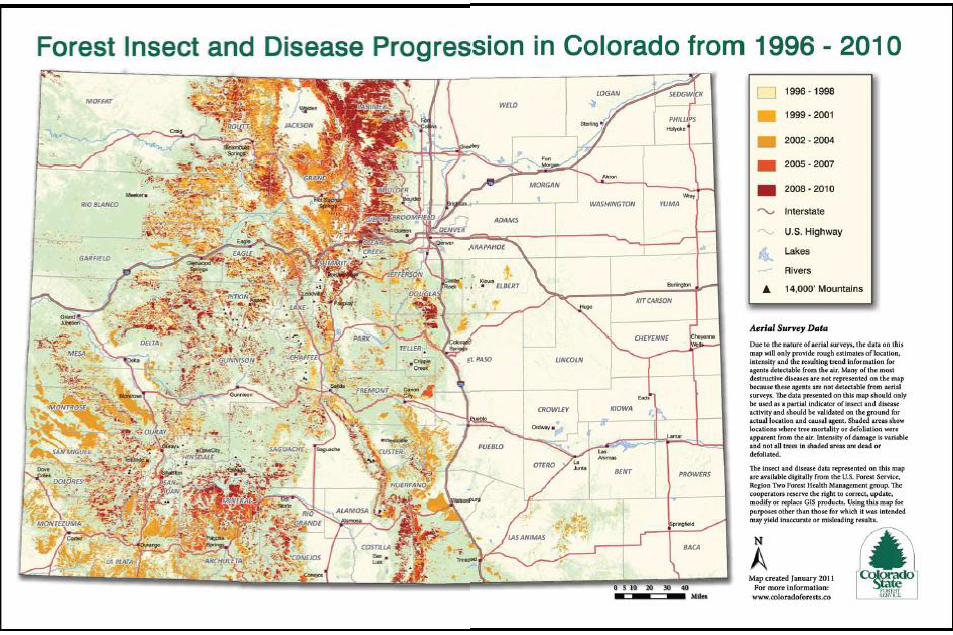

The negative impacts of a landscape level plan that is simply too complex and too specific has had significant impacts on management of major challenges on the Forest, such as the forest ability to deal with Mountain Pine beetle and Spruce Beetle that have decimated the Rio Grande and most other public lands in the Western United State. For reasons that have been long ago forgotten and are simply no longer relevant, the current RMP has numerous provisions that significantly limited manager’s ability to respond to the outbreak of these pests. While the impacts from species certainly could not have been stopped, a streamlined and general forest plan would have allowed managers to respond in a more rapid and timely manner to these challenges and mitigate the impacts to forest health from these species outbreaks. Clearly there will be challenges to forest management being faced later in the Proposals life that managers simply cannot envision at this time. The impacts from these challenges could be minimized with a Proposal that is as simple and streamlined as possible.

1d. Recent Dept. of Interior national guidance on significant reductions in the size of EIS is highly timely relative to Rio Grande efforts.

The Bureau of Land Management has been vigorously addressing the unnecessary scope and burden of planning documents on the limited resources of land managers, and this new guidance from the BLM is highly relevant to USFS efforts on the Rio Grande. While many were shocked at the exceptionally small size of the Proposal and associated documents, under new BLM guidance the Rio Grande effort has resulted documents that are unacceptably long. On August 31, 2017, Secretarial Order 3355[2] was issued by the DOI mandating that all EIS are limited to 150 pages and that a variance from this standard would only be granted in exceptional circumstances. While the Rio Grande planners are not bound by this Order, the factual importance and basic relevance simply cannot be overstated, and clearly the current Proposal would have to be reduced even further from its current streamlined form to become compliant with this guidance.

2a. Three Challenges should be identified in the Proposal and then any standards in the Proposal reviewed to insure they are not impeding management of these issues.

An important component of landscape level planning is the fact that the RMP should provide general guidance on goals for the forest and challenges in achieving these goals in order to streamline subsequent site specific planning on the forest in the most efficient manner possible. The Organizations submit that DOI Secretarial Order 3355 provides a good basis to review the current Proposal in order to obtain further clarity and streamlining in RMP provisions, as the document clearly identifies that the DOI seeks to have any EIS limited to 150 pages in length.

The Organizations commend the RGNF for identifying three major goals for the Forest moving forward, as this is an important first step in the planning process. While public presentations regarding the Rio Grande Plan did identify three major goals for the forest moving forward[3], these goals are not clearly identified in the RMP. The Organizations are concerned that if the goals and objectives of the forest plan are not clearly identified, these concerns will be lost over time which could lead to planning that may seek to address other goals in the future. As these are landscape level goals for the Forest, the Organizations do not see this landscape level guidance as a barrier to future planning but rather as providing an important tool for the guidance of these plans. The Organizations would encourage planners to insert these goals into the RMP with some specificity in order to provide some context and understanding of these goals for future managers on the Rio Grande.

The Organizations would encourage planners to take an additional step and identify three major challenges the forest sees in obtaining these goals and then reviewing any specific standards or guidance in the RMP to insure that the particular standard is working towards minimizing the challenges. The Organizations submit that identifying a limited number of landscape level challenges facing the Forest will serve as an important guide for the development of the RMP and any subsequent localized projects. Identifying these challenges will provide clear and easily reviewable guidance for subsequent projects on the Forest and avoid creation of site specific projects that would contradict the forest level guidance on issues. This will also insure that all actions being undertaken in site specific planning are working towards these forest level objectives and avoids the artificial elevation of issues in local planning. By insuring these challenges are addressed in all planning efforts subsequently, the limited resources that are available to land managers will be directed in the most effective manner in addressing these challenges and actually achieving the goals of the plan.

The Organizations believe that the following challenges reflect the major challenges the forest is facing, and are already reflecting in the supporting documents that have been provided to the public:

- Poor Forest health/large number of dead trees on the Rio Grande NF overall;

- Declining federal budgets will continue to decline and result in the need for stronger partners; and

- Increasing demands being placed on forest resources due to a rapidly increasing State population.

2b. The primary challenge to be addressed on the Rio Grande NF over the life of the next revision of the RMP has to be the poor forest health overall and the large number of dead trees.

The Rio Grande NF has been heavily impacted by the Mountain Pine Beetle epidemic and is on the boundary areas of being heavily impacted by several other invasive species such as the Spruce Beetle. This challenge has to be the first priority to be addressed in the RMP development and the Organizations would note that the Rio Grande NF has already identified poor forest health as the single largest challenge to be faced in their RMP development. These are factors and issues that can be addressed in forest planning to stimulate and streamline timber sales and timber management in conjunction with managed fire to remediate impacts. The Organizations are aware that there is significant pressure on managers to reduce public access to public lands through route closures, but addressing any route specific impacts without addressing the poor forest health simply makes little sense.

Planners must avoid the artificial elevation of issues simply as a result of political pressures or concerns that are not based on issues seen on the Rio Grande. The Organizations vigorously submit that theoretical concerns, such as a groups desire to bring balance and diverse recognition of landscapes into the National Wilderness System are political issues that have been artificially elevated by that Group and simply are not realistic goals in the current funding environment and with the major challenges facing land managers on the Rio Grande. The Organizations are deeply concerned regarding the poor forest health in the Rio Grande as a healthy forest translates into a quality recreational experience for ALL USERS. While any short term recovery of the Rio Grande planning area to a healthy forest status is probably not realistic, major steps can be taken to remediate impacts and return a healthy forest to the public in subsequent generations. Clearly identifying this concern in the Plan will help avoid conflicts in the future.

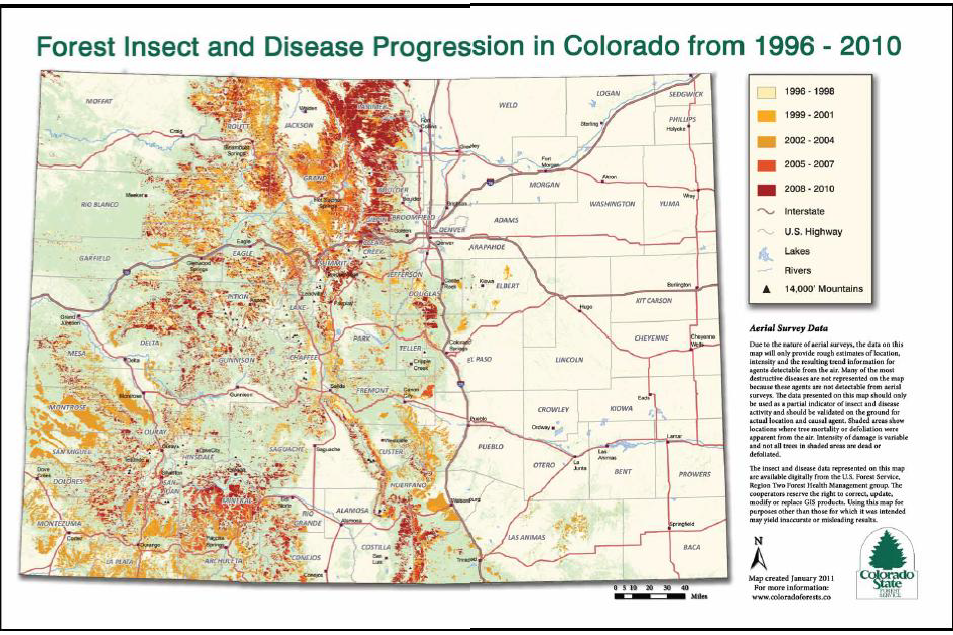

At the landscape level, the Rio Grande NF has the dubious distinction of being the 3rd hardest hit forest in Region 2 in terms of overall forest health, and as poor as current forest health is, USFS estimates project that Forest Health is expected to get significantly worse before getting better. USFS estimates project a total mortality rate of more than 36% for forests on the Rio Grande.[4] This is an issue that simply will take more than the RMP life to resolve and has altered the landscape of the Rio Grande for the foreseeable future.

The Colorado State Forest Service recently issued their annual Forest Health report for the state and the conclusions of these impacts are staggering, especially on water quality.[5] The Highlights of the 2016 report are as follows:

-8% of ALL trees in the state are dead and the rate of mortality is increasing;[6]

– The total number of dead trees has increased 30% in the last 8 years;[7]

– Research has shown that in mid-elevation forests on Colorado’s Front Range, hill slope sediment production rates after recent, high-severity wildfire can be up to 200 times greater than for areas burned at moderate to low severity.[8]

– A 2011 study involved monthly monitoring of stream chemistry and sediment in South Platte River tributaries before and after fire, and showed that basins that burned at high severity on more than 45 percent of their area had streams containing four times the amount of suspended sediments as basins burned less severely. This effect also remained for at least five years post-fire.[9]

– High-severity wildfires responsible for negative outcomes are more common in unmanaged forests with heavy fuel loads than in forests that have experienced naturally recurrent, low-intensity wildfires or prior forest treatments, such as thinning. It is far easier to keep water in a basin clean, from the source headwaters and through each usage by recipients downstream, than to try and restore water quality once it is degraded.[10]

–During 2016’s Beaver Creek Fire, which burned 38,380 acres northwest of Walden, foresters and firefighters were given a glimpse into likely future challenges facing wildfire suppression and forest management efforts. These include longer duration wildfires due to the amount and arrangement of heavy fuels. Observations from fire managers indicated that instead of small branches on live trees, the larger, dead fuels in jackstraw stands were the primary driver of fire spread…. “The hazards and fire behavior associated with this fuel type greatly reduce where firefighters can safely engage in suppression operations”[11]

The Colorado State Forest System has prepared an annual report on the declining forest health in the State for more than a decade and copies of these reports are available on their website. Clearly, even the worst site specific issues with any trail or road will never result in impacts comparable to those impacts addressed above and managers should remain most focused on addressing these challenges. These are landscape level challenges that must be addressed with landscape level management.

USFS research indicates there is a huge correlation between Congressionally designated Wilderness and areas hardest hit by invasive species. A copy of this research conclusions are below. Research from the Colorado State Forest Service confirms that the minimal management allowed for forest health in Congressionally designated Wilderness areas has dramatically impacted forest health in the Rio Grande planning area.

Given the fact that 1 in 12 trees in the entire state of Colorado is dead, and based on the Organizations experience the Rio Grande rates of forest mortality is significantly higher than the state average and that amount is increasing rather than even stabilizing, the Organizations must be opposed to any new management standards that would make timber management more difficult or impossible. Management standards simply must remain focused on the major challenges on the Rio Grande in order to address these issues. The need to meaningfully address this challenge is compounded by projections from the USFS that Forest health with degrade even more significantly before ever improving. The Organizations vigorously assert that a healthy and sustainable forest is a critical component to ALL recreational activities in and around the Rio Grande and to the high quality of life that is associated with the communities in the planning area. The Organizations would also urge land managers to resist assertions that other smaller challenges are posing a similar scale threat to the Rio Grande planning area.

The relationship of poor forest health and heightened restrictions on management of public lands has also been repeatedly addressed by the USFS researchers. In a Rocky Mountain Research Station report reviewing the USFS response to the bark beetle outbreak, management restrictions were clearly and repeatedly identified as a major contributing factor to the outbreak and a major limitation on the response. This report clearly stated:

- Limited accessibility of terrain (only 25% of the outbreak area was accessible due to steep slopes, lack of existing roads, and land use designations such as Wilderness that precluded treatments needed to reduce susceptibility to insects and disease).[13]

- In general, mechanized treatments are prohibited in designated wilderness areas. The Arapaho Roosevelt, White River, and Routt National Forests in Colorado have a combined total of over one million acres of wilderness; the Medicine Bow National Forest in Wyoming has more than 78 thousand acres. A large portion of these wilderness acres have been impacted by the current bark beetle outbreak.[14]

- Owing to terrain, and to budgetary, economic and regulatory limitations—such as prohibitions on entering Roadless areas and designated wilderness—active management will be applied to a small fraction (probably less than 15%) of the forest area killed by mountain pine beetles. Research studies conducted on the Sulphur Ranger District of the Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest help us understand the implications of this situation.[15]

With clear management concern regarding the impacts of restrictive management on the pine beetle response, the Organizations must question any restrictions on active management of Rio Grande resources moving forward.

Many other researchers are now recognizing the negative impacts of Congressionally designated Wilderness on Forest Health and the ability to manage these areas in response to the challenges presented by the changing climate of the planet. In a review of pine blister impacts to forests in the Bob Marshall Wilderness area, researchers again concluded that the

Again these areas were much more heavily impacted than adjacent areas where management had been more active in nature. While this portion of the comments is addressing Congressionally Designated Wilderness, the challenges are the same as much that can be addressed in the RMP, such as Recommended Wilderness Designations. Rio Grande managers have already had to deal with RMP standards that complicated the response to challenges, such as limitations on treatments of invasive species in certain management areas, the Organizations submit that imposing this type of management on future managers simply makes little sense and should be avoided. Given the clearly negative relationship between heightened management restrictions in any area and more rapid and severe impacts to forest health, the Organizations must express serious concerns regarding any management in the new RMP that made addressing forest health issues more difficult.

The Organizations concerns regarding the elevation of abstract concepts to sufficient level as to interfere with major challenges on the Rio Grande is exemplified by the fact that Timber management activities are prohibited within ½ mile of the CDT as follows:

“National Scenic and Historic Trails – Continental Divide National Scenic Trail and Old Spanish Trail including a ½ mile buffer on each side”[17]

No mention of the fact that the Rio Grande is one of the hardest hit forest in Region for both Mountain Pine Beetle and Spruce Beetle is addressed in this portion of the RMP.

Impacts of these management decisions to all other activities are more clearly identified in the DEIS for the Rio Grande NF, where exclusionary corridors are clearly identified as a minimum of ½ mile and expanding to 1 mile in certain management areas.[18] The Organizations vigorously submit that management standards such as this make absolutely not sense and have clearly been inserted without meaningful analysis. Not only will this complicate future management of major challenges, such as undertaken a removal of hazard trees on the CDT, this type of standard is also a direct violation of the National Trails System act, which requires a maximization of values of lands along the trail and meaningful analysis of all economic activity in and around the trail. Clearly trees have value and their removal has a long history of being an economic driver in Colorado.

2c. Forest Service budgets will continue to decline over time.

The Organizations are intimately aware of the ongoing budgetary challenges that are facing federal land managers and the fact that the budgetary declines are not anticipated to rebound. The changing budgetary situation facing federal land managers presents a major challenge for land managers moving forward, as the Organizations are aware that often partner support is high when new facilities or routes are being constructed but also tends to wane when basic operational expenses are addressed. Land managers consistently inform us that basic operational activity, such as maintaining routes, cleaning toilet facilities and trash removal have consistently become more expensive and now pose major challenges for managers moving forward due to ever declining funding for operations. The Organizations believe that the RMP revision provides a great opportunity to highlight this challenge and guide site specific projects in a manner that maximizes not only the short term partner funding relied on for construction but also the long term programmatic type funding that is becoming a more important factor in providing all recreational opportunities.

2d. USFS partnerships reports could provide high quality information on partner resources.

With the passage of the National Forest System Trails Stewardship Act in 2016, Congress mandated the creation of a volunteer strategy report to improve partnerships between land managers and user groups for the benefit of trails on federal public lands. While this report is not to be published until 2018, this report should be highly relevant in addressing budgetary shortfalls and identifying partners where resources are more limited and partners where resources are more available as the report requires:

“(b) REQUIRED ELEMENTS.—The strategy required by subsection (a) shall—

(1) augment and support the capabilities of Federal employees to carry out or contribute to trail maintenance;

(2) provide meaningful opportunities for volunteers and partners to carry out trail maintenance in each region of the Forest Service;

(3) address the barriers to increased volunteerism and partnerships in trail maintenance identified by volunteers, partners, and others;

(4) prioritize increased volunteerism and partnerships in trail maintenance in those regions with the most severe trail maintenance needs, and where trail maintenance backlogs are jeopardizing access to National Forest lands; and” [19]

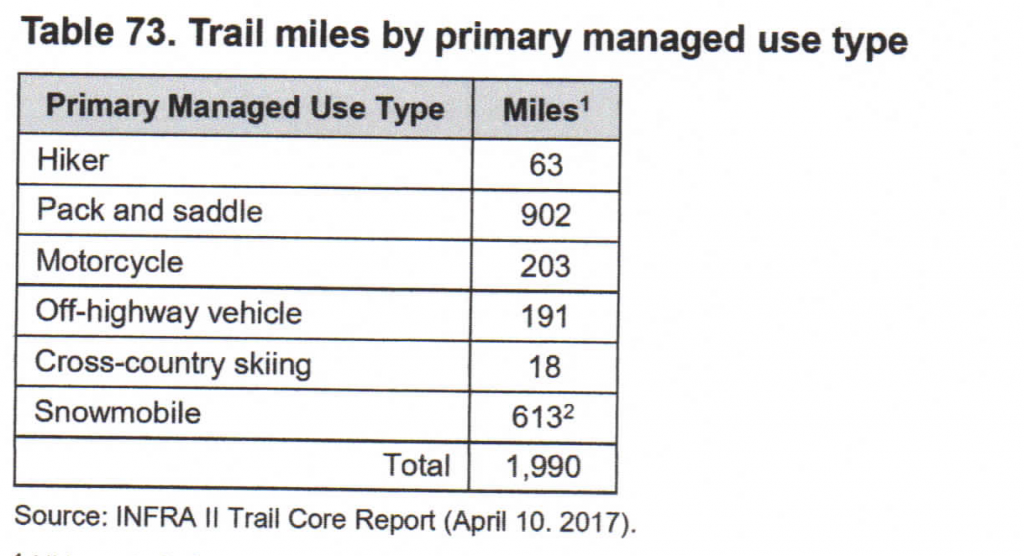

The largest single partner with both the BLM and USFS in Colorado is the motorized trail user community, both in terms of direct funding to land managers through the CPW Trails Program and with direct funding and resources from clubs in the Rio Grande planning area. The partnerships impact is further expanded by the fact that all motorized routes on the Rio Grande are available for all other recreational activities. A major barrier to partnerships is closures of routes due to resource concerns when resources are available to address the resource concerns that are the basis of the route closure and the failure to treat all recreational user groups in a similar manner.

The identification of partner resources available to Rio Grande managers must be a major priority in the development of the RMP as well. While there are many partner groups who volunteer time and resources in partnership with Rio Grande managers, the OHV community is the only partner that provides direct and consistent funds to Rio Grande managers through the CPW OHV grant program to assist in achieving sustainable recreational opportunities. The USFS Regional office has clearly identified that just the OHV program in Colorado more than doubles the amount of agency funding that is available for recreational activity on USFS public lands. After a review of the CPW Statewide Good Management Crew program based in the Sulphur Ranger District of the Arapahoe/Roosevelt NF managers clearly identified that CPW OHV good management crews were provided money in a more consistent and timely manner than the funding that was provided through USFS budgeting and over time the CPW program funding had significantly increased while USFS budgets had significantly declined. There is simply no basis for a decision that this long term reduction in funding will change and this should be factored into planning for projects on the ground for all user groups.

In 2017, Rio Grande managers asked for almost $200,000 in direct funding for annual maintenance crews and for site specific projects from the CPW OHV program alone. This funding provides three trained seasonal crews who perform on the ground trail maintenance, provide basic maintenance services for more developed sites and expand the law enforcement presence on the Rio Grande. Additionally, these crews are able to leverage a significant amount of mechanized equipment in the Rio Grande planning area, such as the several Sutter trail dozers, mini-excavators and tractors owned by local clubs to address larger maintenance challenges in a very cost effective manner.

In addition to the OHV grant funding and exceptional partnerships available through summer use clubs, CPW funding through the Snowmobile Registration Program provides an additional $500,000 in funding to local clubs for operation of the grooming programs, who maintain almost 400 miles of multiple use winter trails on the Rio Grande. The CPW snowmobile registration program further partners with the local clubs to purchase grooming equipment used on these routes, which now is consistently exceeding $200,000 to purchase used. This CPW funding is again leveraged with exceptional amounts of volunteer and community support for these grooming programs from local clubs and often times the CPW funding is less than half the operational budget for the clubs maintaining these routes. These winter trails are the major access network for all users of Rio Grande winter backcountry for recreation and all these opportunities are provided to the general public free of charge.

While there has been a significant decline in direct funding through the agency budget process, motorized partners on the Rio Grande have been able to marshal resources at levels that are unheard of other forests for the benefit of all recreational users. The Organizations would ask that if budget constraints are identified as a challenge for recreational usage of the forest moving forward, that these constraints are applied to all recreational usages and that the fact that the Rio Grande has been the beneficiary of some of the strongest partnerships with the motorized community in the country for literally decades be properly balanced in addressing any budget shortfalls.

3a. Growing state populations will continue to seek recreational opportunities on public lands.

The Organizations believe that the third major challenge that will be faced by managers on the Rio Grande will be significant increases in the population of communities in the Rio Grande planning area and the expansion of utilization of Rio Grande opportunities by those living on the Front Range of Colorado. These new visitors to the Rio Grande area will continue to expect the high quality recreational opportunities that have become synonymous with the Rio Grande. Compounding this challenge will be the fact that USFS resources are declining slowly in terms of absolute dollars and declining far more rapidly in terms of that funding ability to address challenges on the Forest. This relationship results in a critical need for the RMP to facilitate the management and maintenance of Rio Grande lands in the lost cost effective manner possible and avoid placing unnecessary restrictions or prohibitions on the management of areas on the Rio Grande.

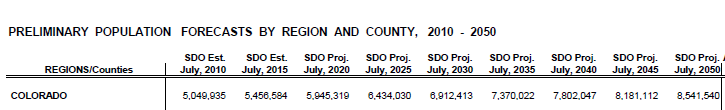

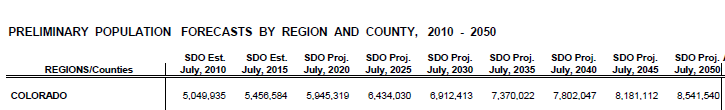

The Colorado State Demographer estimates that the Colorado population is expanding at a rate of more than 100,000 citizens per year and will almost double by the year 2050. The Demographer breaks down this forecast as follows:

The Organizations would be remiss if the relationship of the time needed to double the state population and the anticipated life span of the Rio Grande RMP was not raised as a significant basis for our support of Alternative C. While Projections estimate that a large portion of the population will settle along the Colorado Front Range and not be living directly within the Rio Grande planning area, the Organizations submit that these residents will still seek out the high quality recreational opportunities that have become synonymous with Colorado. The Organizations believe that the RMP should strive to maintain current levels of access and meaningfully address areas where recreational access can be expanded in order to address this expanded usage in a thoughtful manner that protects resources and provides opportunities. Failing to address this expanding demand will not stop the population from visiting public lands but rather will result in low quality opportunities being provided, unnecessarily planning being required and resources being impacted as a result of the lack of planning. Again this must be avoided as much as possible in the RMP.

3b. Planning flexibility must be provided to expand recreational facilities and opportunities.

The Organizations believe that addressing the three major challenges in addressing the goals of the forest plan is an important component of the revision of the forest plan. Given population projections, current facilities and opportunities will become insufficient in providing opportunities. The RMP standards should be reviewed in insure that future managers will be able to address this situation in a meaningful and effect way.

Currently there are standards throughout the RMP where future managers would be limited by such a response. This limitation in planning exemplified by standard MA-Rec-10 of the Proposal, which provides as follows:

“MA-REC-10: If use exceeds the area capacity for a given recreational opportunity spectrum class, the following management actions should be employed to address the impacts or effect on the recreation setting:

- Inform the public and restore the site.

- Regulate the use.

- Restrict the number of visitors.

- Close the area or site (Forestwide).”[21]

The Organizations vigorously assert that this exemplifies the type of standards that must be reviewed in the plan to insure that the RMP does not become a management barrier moving forward. Under this management standard, there are no provisions that allow for new facilities and opportunities to be brought on line to address capacity issues being exceeded. This standard could be amended to allow expansion with inclusion of subsequent site specific planning. This type of landscape flexibility has been an important component of any discussion around recreational opportunities, and given the explosive population growth in the State the assumption that current recreational facilities will be able to accommodate expanded demand is probably on a questionable factual basis.

The current version of MA-REC-10 also represents the type of standard that has been put in place in the RMP without meaningful analysis or discussion in the Proposal. The Organizations hope that the failure to include any expansion of opportunities to other areas as a tool for addressing overuse of existing facilities was not intentionally included in the Proposal, as this would be very concerning to the Organizations.

How did planners determine this limitation was relevant? The RMP simply does not address this. This lack of factual basis will complicate any subsequent site specific planning that might be seeking to expand opportunities into new areas of the forest as the result of the capacity being exceeded at an existing facility. In twenty years this type of standard could be seen as a frustrating barrier to management in a manner similar to the frustrations that current managers have experienced with current management provisions addressing limited authority to treat and manage the impacts of invasive species on the forest. These types of issues simply must be avoided.

4. Why the Organizations are supporting Alternative C of the Proposal.

The Organizations are supporting Alternative C of the Proposal due to the limited number of management standards that are provided for in this Alternative, which is a significant benefit for the reasons previously addressed in these comments. The Organizations also support the significant expansion of opportunity areas for motorized recreation that are provided in the Alternative, but this is not unexpected and our reasoning behind such a position should be apparent. The Organizations believe the flexibility provided under the expanded multiple use opportunity areas is an important factor to be addressed in the RMP as increasing populations in Colorado will continue to demand high quality opportunities synonymous with Rio Grande. Site specific planners should have the most flexibility possible in their planning, and authority to allow multiple use should be provided in the RMP as this can be more meaningfully addressed in local planning.

The Organizations also support Alternative C due to the inherent simplicity of the Plan that results from the reduced number of management categories in the RMP. The Organizations are well versed in site specific planning that occurs subsequent to the implementation of an RMP, and while planners attempt to streamline the subsequent site specific planning efforts by identifying a large number of issues and factors in the landscape level RMP, often times these efforts become outdated quickly and result in significant barriers resulting in site specific planning rather than streamlining local site specific plans.

The significant reduction in the number of categories of the RMP Alternative C will also result in increased simplicity for the public and allow for a much greater level of understanding of the Plan. This alternative is the easiest for the public to understand for comments and for the public to understand how the Plan will guide management of particular areas to achieve particular goals in the future. The most common frustration we have experienced in dealing with the public in working on site specific projects on forest is the high levels of complexity of forest plans, the numerous overlapping categories for the management of areas that often provide contradictory and confusing guidance for areas and rely on boundaries that make little sense on the ground or rely on boundary lines in the forest plan that are of such poor definition due to mapping scales that conflict results. These benefits should not be overlooked.

Our reasoning for support of Alternative C is not just limited to recreational concerns. Alternative B misses the boat when it comes to actively managing the Forest, protecting local jobs, and ensuring there is a forest in the future. The proposed action (Alternative B) proposes to:

- Only cut 40,000 CCF of salvage per year for the first decade, and only 15,600 CCF of green treatment per year in the second decade. This is not enough wood to supply the current industry.

- Recommends an additional 59,000 acres of wilderness, thus making management even more difficult.

- Recommends two different fire management zones, including “resource restoration” where wildfires may be allowed to burn to achieve “resource objectives,” which is very concerning for the suitable timber acres. How many times has the Forest Service burned up valuable areas?

- Rather than making the plan easier to read and understand, Alternative B proposes to have almost the same exact number of management zones as currently exists, as well as the new fire management zones.

Overall, Alternative C is the best choice for managing the Rio Grande National Forest as a multiple-use forest while still achieving the desired ecological, social, and economical goals. Here is what Alternative C proposes to accomplish for timber management:

- Salvage up to 70,000 CCF of timber per year for the first decade, followed by 22,000 CCF of green treatment during the second decade.

- Proposes zero acres of new wilderness. Currently, only 17% of the entire 1.83 million acres is considered suitable for timber production. Adding more wilderness acres will simply reduce the number of suitable timber acres.

- Simplifies the plan by reducing the overall number of management areas.

Given these stark differences in the ability of managers to address what the Organizations see as the single largest management challenge on the Rio Grande over the life of the next plan, these differences are critically important to why the Organizations are supporting Alternative C of the Proposal. It simply does a better job of addressing challenges, and the Organizations would support any efforts to further streamline even Alternative C of the Proposal to address challenges or shorten the Proposal.

5. The Organizations are vigorously opposed to Alternative D.

The Organizations are VIGOROUSLY opposed to Alternative D of the Proposal due to the significant restrictions it places on multiple use access to the forest and the complications to the removal and mitigation of poor forest health on the forest that would result from expanded management restrictions in Alternative D. Alternative D would also remove motorized trails from Colorado Roadless areas, which the Organizations submit is in direct conflict with the Colorado Roadless Rule statements that clearly identifies dispersed motorized opportunities as a characteristic of a Colorado Roadless Area. Alternative D also provides for an additional 285,000 acres of recommended Wilderness on the Rio Grande. The Organizations are opposed to this decision as this would be 285,000 of the forest where addressing poor forest health would be made more difficult in the future because of the RMP. This simply makes no sense.

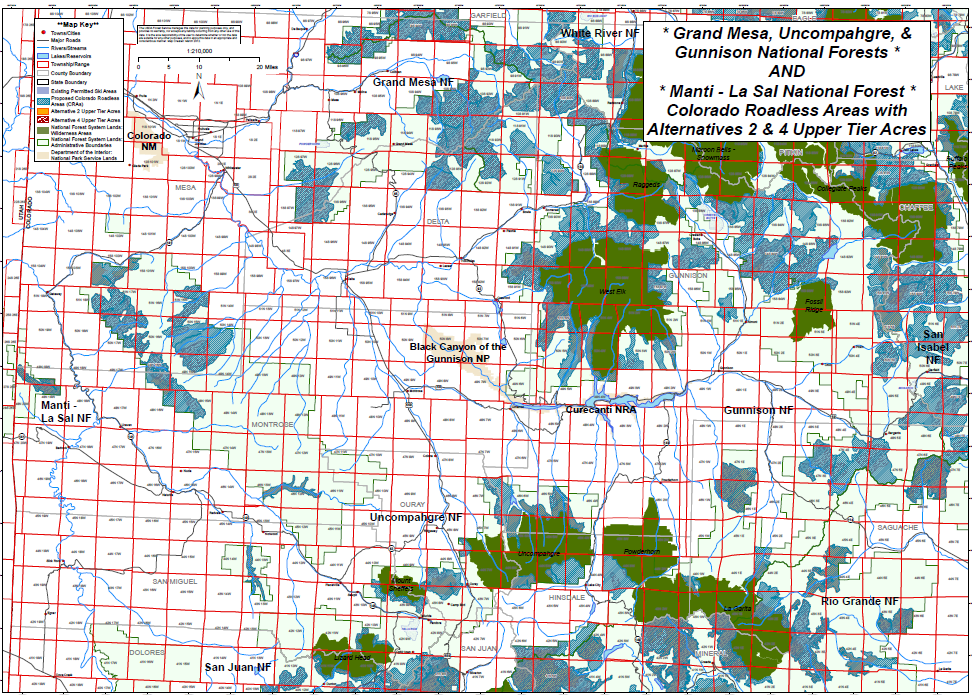

6. The Colorado Roadless Rule must be accurately applied in the Rio Grande RMP, which directly applies to Area 3.5 and 3.6 management prescriptions.

The Organizations submit that the development of the Colorado Roadless Rule (“CRR”) is generally poorly understood by many of the groups submitting comments in favor of expansion of Wilderness and Recommended Wilderness in the Planning Process. The Organizations submit the CRR development was an extensive site specific analysis of many of the same areas that have been the basis for possible Wilderness designations in the past and the CRR provided clear guidance for development of non-Wilderness management of these areas. Part of the intent of the CRR was that as management of these areas moved into the future, the never ending discussion of possible designation of these areas could be avoided. The CRR clearly states that no further protections of these areas is warranted and that the characteristics inventoried should be protected and preserved.

The Organizations were actively and extensively involved in the development of the CRR with the USFS, and can assert without hesitation that the CRR sought to provide a dispersed recreational experience for all users, which is a significant difference from the position asserted by the Wilderness Society in their comments on this issue. The Organizations submit that any interpretation of the CRR in the manner asserted in the Wilderness Society comments twists both the direct language of the CRR and the spirit and intent in developing the CRR as large portions of the Rio Grande were reviewed as possible Upper Tier areas and then specifically found unsuitable for such designation. Application of this twisted version of the CRR must be avoided in the development of the Rio Grande RMP as this alternative management of many areas on the Rio Grande as Upper Tier areas was specifically reviewed in the development of the CRR and was declined to be implemented.

While the Roadless Rule never altered the multiple use mandates for any areas, the development of the Colorado Roadless Rule went a step further on multiple uses and specifically identifies motorized usage as a characteristic of a Colorado Roadless Area. The CRR specifically states this as follows:

“Roadless areas are, among other things, sources of drinking water, important fish and wildlife habitat, semi-primitive or primitive recreation areas, including motorized and nonmotorized recreation opportunities, and natural-appearing landscapes. There is a need to provide for the conservation and management of

Roadless area characteristics.”[22]

Documents developed around the CRR further clearly state this relationship as follows:

“The final rule does not prohibit use of existing authorized motorized trails nor does it prohibit the future development of motorized trails in CRAs (see 36 CFR 294.46(f)). The final rule allows continued motorized trail use of CRAs if determined appropriate through local travel management planning.”[23]

The utilization of CRR and Upper tier Roadless areas was further specifically addressed in the EIS issued with the 2012 Roadless Rule. The EIS provides additional clarity regarding the importance of motorized usage of both types of Roadless areas, providing as follows:[24]

| Recreational use: motorized | Value focuses on maintaining current motorized use of Roadless areas for recreational opportunities, as well as, where appropriate, increasing backcountry motorized opportunities in the future, which may be trails/single-track rather than roads. |

The FEIS additionally clearly identified the significant differences between a Roadless areas and other management areas as follows:

“These Roadless areas provide settings for dispersed recreational activities that are prohibited in designated wilderness areas and not readily available in developed or modified settings with system roads. For example, wilderness areas prohibit, with few exceptions, mechanized and motorized uses, such as OHVs, mountain bikes, and snowmobiles. Within Roadless boundaries, these activities are permitted on designated trails, including current and new trail construction. Wheelchair or handicapped access is allowed within wilderness areas, but is expected to be very challenging. Depending on the travel management direction for an individual Roadless area, many trails within Roadless areas are open to OHV use for those who are not able to access remote areas without motorized assistance.”[25]

The Organizations believe that proper application of the CRR review and analysis process provides significant information regarding areas that should not be managed in a manner similar to Wilderness. Under this review, a significant portion of the Rio Grande planning area was specifically reviewed for possible Upper Tier Roadless designation and found to be unsuitable.

Given that a large portion of the Non-Wilderness areas in the Rio Grande planning area where recently inventoried for possible increases in management to levels that remained below Congressionally designated Wilderness, the Organizations must question what situation or condition has changed in these areas that would allow these areas to become suitable for Wilderness recommendations in the RMP within such a short period of time.

In addition to the CRR providing clear guidance regarding the desire for these areas to be managed for expanded low intensity motorized usage, the CRR also clearly stated that trail development was to be allowed in both areas. While the RMP does provide a reasonable summary of usages of CRR in the management provisions, such as 3.5 and 3.6, trail construction is not addressed in the RMP and as a result this lack of clarity will result in questions on site specific planning for these areas in the future. Mainly the Organizations are concerned that in the future there will be questions involving if these standards intended to omit trail construction from these areas or should the CRR be directly applied? The Organizations request that if some uses are going to be identified in the RMP, multiple use trail construction must be specifically and clearly identified as well, or all discussion of uses should be removed. Under the current version of the RMP, ambiguity is created on this issue rather than clarity for future management. This again must be avoided.

7a. Continental Divide Trail management and corridor usage must be governed by multiple use principals.

The Organizations are aware of extensive discussions and pressure from certain interest groups surrounding the management of National Scenic Trails and National Historic Trails on numerous other forests, as exemplified by discussions around the Pacific Crest Trail as it travels through the Lassen, Tahoe, Stanislaus and Plumas National Forests in California as these are moving through winter travel planning Unfortunately these discussions have now been raised in public meetings involving the Rio Grande RMP revision. While these discussions are often passionate and filled with an artificial urgency to save the world from a falling sky, this position simply lacks any basis as it conflicts with the direct language of the National Trails System Act, the intent of Congress in passing the NTSA, the specific language of the Trail related NEPA plans and numerous other Executive Orders regarding recreation and cost benefits analysis.

Numerous standards are proposed in the Rio Grande NF RMP that could result in exclusionary corridors being developed in subsequent site specific planning around the CDT. Often pressure and efforts of groups asserted that national trails system routes must be non-motorized under the National Trails Act are based on incomplete or inaccurate reviews of the National Trails System Act, which can be easily achieved due to the poor drafting of the NTSA and the following provisions are included in the hope of bringing balance to these discussions. Unfortunately these incomplete and conflicting summaries have now been included in USFS Guidance on NTSA designated routes. The Organizations must briefly address the management history of the Continental Divide Scenic Trail and the specific statutory provisions addressing both the CDT and the usage of public lands in areas adjacent to the CDT. Prior to addressing the clarity of the current NTSA, a review of the intent of Congress and competing interests at the time of passage of the NTSA is relevant. Corridors excluding usages violates the NTSA directly, minimizes values and will lead to unprecedented conflicts between users that simply does not exist at this time.

The Organizations concerns regarding exclusionary corridors are not abstract as many facilities of other users and management activities are proposed to be excluded prohibited within ½ mile of the CDT . An example of this type of standard in the RMP is as follows:

“National Scenic and Historic Trails – Continental Divide National Scenic Trail and Old Spanish Trail including a ½ mile buffer on each side”[27]

Such a standard simply makes no sense when the public safety risk that results from the large number of hazard trees along the CDT is reviewed. No mention of the fact that the Rio Grande is one of the hardest hit forest in Region for both Mountain Pine Beetle and Spruce Beetle is addressed in this portion of the RMP.

Impacts of these management decisions to all other activities are more clearly identified in the DEIS for the Rio Grande NF, where exclusionary corridors are clearly identified as a minimum of ½ mile and expanding to 1 mile in certain management areas.[28] Under certain management alternatives, exclusionary corridors would prohibit significant recreational opportunities which may be visible in the viewshed such as level 1 roads, trails, 2 scenic byways, and some campgrounds and recreation areas. [29] Again the Organizations vigorously oppose the complete lack of analysis around this type of a corridor as clearly these impacts have not been reviewed in any manner in the EIS and represent a direct violation of the NTSA, as more completely outlined below. The Organizations also submit these type of arbitrary management standards in an RMP are exactly the type of standards that make any future site specific planning more expensive and difficult as planners are simply unable to address the management concern that resulted in these management standards.

7b. Mandatory exclusionary corridors directly conflict with the Congressional intent when NTSA was passed.

The management of NTSA corridors and routes has a long and sometime conflicting management history when only legislation is reviewed but significant clarity in Congressional intent for management of routes and corridors is provided with the review of Congressional reports provided around passage of the NTSA. Additionally every time Congress has spoken regarding these alleged conflicts the NTAS has been amended to include stronger language in favor of multiple use and opposing corridors.

Extensive background regarding multiple uses of corridors and trails designated under the NTSA was originally addressed in House Report 1631 (“HRep 1631”) issued in conjunction with the passage of the NTSA in 1968. A complete copy of this report is submitted with these comments for your convenience. While there are numerous Congressional reports referenced in the 2016 USFS CDT guidance, many of which have not been provided to the Congressional offices for release to the public, HRep 1631 is simply never mentioned despite it being a foundational document in the discussion. Such conflicts should be problematic for managers seeking to implement recommendations of USFS Guidance on the NTSA as Congress has repeatedly had the opportunity to require exclusionary corridors around NTSA routes, but has consistently moved towards more clarity in addressing multiple usage of these areas.

HRep 1631 provides detailed guidance regarding the intent of the Legislation, and options that Congress declined to implement in the Legislation when it was passed. It is deeply troubling to the Organizations that USFS guidance relies on numerous legislative documents, many of which are unavailable to the public,[30] but this highly relevant legislative document is never addressed in the USFS Guidance. HRep 1631 provides a clear statement of the intent of Congress regarding multiple usages with passage of NTSA, which is as follows:

“The aim of recreation trails is to satisfy a variety of recreation interests primarily at locations readily accessible to the population centers of the Nation.”[31]

The Organizations note that satisfaction of a variety of recreation interests on public lands simply is not achieved with the implementation of any width corridor around a usage or trail. Rather than providing satisfaction for all uses, implementation of mandatory corridors will result in unprecedented conflict between users. This simply must be avoided.

While HRep 1631 is not addressed in 2016 USFS CDT guidance, the direct conflict of the agency guidance and this report simply cannot be overlooked. Much of the information and analysis provided in HRep 1631 is highly relevant to the authority of USFS guidance assertions that 1-mile corridors is mandatory or even recommended. HRep 1631 clearly and unequivocally states Congress declined to apply mandatory management corridors of any width in the Legislation. HRep 1631 states:

“Finally, where a narrow corridor can provide the necessary continuity without seriously jeopardizing the overall character of the trail, the Secretary should give the economics of the situation due consideration, along with the aesthetic values, in order to reduce the acquisition costs involved.”[32]

Congress also clearly identified that exclusionary corridors would significantly impair the ability of the agencies to implement the goals and objectives of the NTSA as follows:

“By prohibiting the Secretary from denying them the right to use motorized vehicles across lands which they agree to allow to be used for trail purposes, it is hoped that many privately owned, primitive roadways can be converted to trail use for the benefit of the general public.”[33]

HRep 1631 clearly addresses the intent of Congress, and the internal Congressional discussions regarding implementation of the NTSA provisions for the benefit of all recreational activities as follows:

“However, they both attempted to deal with the problems arising from other needs along the trails. Rather than limiting such use of the scenic trails to “reasonable crossings”, as provided by the Senate language, the conference committee adopted the House amendment which authorizes the appropriate Secretaries to promulgate reasonable regulations to govern the use of motorized vehicles on or across the national scenic trails under specified conditions.”[34]

Rather than conveying the clear intent of Congress to avoid corridors as a part of management of an NTSA route, on page one of the 2016 CDT guidance clearly states that such a corridor is the preferred management tool, stating as follows:

“The CDT corridor/MA should be wide enough to encompass the resources, qualities, values, associated settings and primary uses of the Trail. The 0.5 mile foreground viewed from either side of the CDT must be a primary consideration in delineating the CDT corridor/MA boundary (FSM 2353.44b (7)).”[35]

The Organizations are simply unable to theorize any situation where the intent of Congress in passing the NTSA and the 2016 CDT guidance can be reconciled as Congress specifically stated that corridors should not be applied and managers retain authority to address site specific issues and challenges. This is deeply concerning given the fact that if Congress has specifically looked at a management tool and specifically declined its application, any implementation of such a tool in management is problematic. This type of direct material conflict is not mitigated with the passage of time especially when the clearly stated intent of Congress was to satisfy a variety of recreational interests with the passage of the NTSA. The Organizations vigorously assert that only those interests protected by the corridor would be satisfied with a corridor, and this must be avoided.

7c. Congress has consistently declined to require minimum exclusionary corridors around NTSA trails.

Management of the CDT is specifically governed by the National Trail System Act (NTSA) which specifically addresses multiple usage of areas adjacent to trails and how these multiple use mandates will relate to management of the trail. The NTSA provides as follows:

“In selecting the rights-of-way full consideration shall be given to minimizing the adverse effects upon the adjacent landowner or user and his operation. Development and management of each segment of the National Trails System shall be designed to harmonize with and complement any established multiple use plans for that specific area in order to insure continued maximum benefits from the land.“[36]

The Organizations believe that Congress was very clear in these provisions, as they clearly stated maximum benefits from the land and harmony with multiple use planning was the objective. The Organizations submit that maximum benefits from the land as a management standard is a FAR more encompassing standard of management than maximizing benefit of the trail or an area to the users of the trail.

While the NTSA does provide that multiple uses are not allowed on an NTSA route in Wilderness Areas, National Wildlife Areas, and National Parks among other areas where such usage would be prohibited in 1968, the NTSA makes no mention of prohibitions for usage outside these areas. The Organizations submit that any buffer corridor expanding these prohibitions outside these areas would be a violation of this specific management standard and the Organizations are not able to understand how designating a corridor in the Resource management plan would not be a violation of these standards as the conflict would directly involve the multiple uses in the RMP rather than being implemented in subsequent planning. Congress has prohibited exclusionary corridors at any time around an NTSA route.

The NTSA also provides guidance on the large scale relocation of any Congressionally designated scenic trail from its original location as the NTSA continues as follows:

“Relocation of a segment of national, scenic or historic trail….A substantial relocation of the rights of way for such a trail shall be by Act of Congress.” [37]

While Congress was clear on the desire to retain authority over the alteration of any National Trail, the failure to define “significant” places any changes in a national scenic trail from its original location, in the case of the CDT the 1977 report to Congress outlining its location, on questionable legal basis.

In several locations in the NTSA, proper recognition of multiple usage of a National Trail is specifically and clearly identified in areas outside Wilderness, Parks and National Wildlife Refuges. The NTSA explicitly provides allowed usages as follows:

“j) TYPES of trail use allowed. Potential trail uses allowed on designated components of the national trails system may include, but are not limited to, the following: bicycling, cross-country skiing, day hiking, equestrian activities, jogging or similar fitness activities, trail biking, overnight and long-distance backpacking, snowmobiling, and surface water and underwater activities. Vehicles which may be permitted on certain trails may include, but need not be limited to, motorcycles, bicycles, four-wheel drive or all-terrain off-road vehicles. In addition, trail access for handicapped individuals may be provided. The provisions of this subsection shall not supersede any other provisions of this chapter or other Federal laws, or any State or local laws.”[38]

The Organizations would note that given the specific recognition of snowmobiling, four wheel drive and all-terrain vehicles as allowed trail usages, any attempt to exclude such usages from the CDT would be on questionable legal ground. In addition to the above general provisions regarding multiple usage in areas around a National Scenic Trail, multiple usage of the Continental Divide Scenic Trail is also specifically and repeatedly addressed and protected in the NTSA. The CDT guidance starts as follows:

“Notwithstanding the provisions of section 1246(c) of this title, the use of motorized vehicles on roads which will be designated segments of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail shall be permitted in accordance with regulations prescribed by the appropriate Secretary.”[39]

The NTSA further addresses and protects multiple usage of the CDT is further addressed as follows:

“Where a national historic trail follows existing public roads, developed rights-of-way or waterways, and similar features of man’s non historically related development, approximating the original location of a historic route, such segments may be marked to facilitate retracement of the historic route, and where a national historic trail parallels an existing public road, such road may be marked to commemorate the historic route. Other uses along the historic trails and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, which will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the trail, and which, at the time of designation, are allowed by administrative regulations, including the use of motorized vehicles, shall be permitted by the Secretary charged with the administration of the trail.“[40]

In addition to the specific provisions of the NTSA addressing the CDT, the CDT management plan further addresses multiple usage including the high levels of multiple use on the CDT in 2009. The CDT plans specifically states:

“(2) At the time the Study Report was completed (1976), it was estimated that approximately 424 miles (14 percent) of existing primitive roads would be included in the proposed CDNST alignment.”[41]

While the CDT plan does recognize levels of roads utilization, the CDT plan does not specifically address the miles of multiple use trail that are aligned along the CDT. Motorized Trail usages of the CDT and corridor are critically important to winter motorized usage on the San Juan and many other locations as significant portions of the CDT are groomed by the motorized community for the benefit of all users. Rather than providing specific analysis of this usage the CDT plan provides that trails adopted through the travel management process are an allowed usage of the CDT, providing as follows:

“Motor vehicle use by the general public is prohibited on the CDNST, unless that use is consistent with the applicable land management plan and:

(1) Is necessary to meet emergencies;

(2) Is necessary to enable adjacent landowners or those with valid outstanding rights to have reasonable access to their lands or rights;

(3) Is for the purpose of allowing private landowners who have agreed to include their lands in the CDNST by cooperative agreement to use or cross those lands or adjacent lands from time to time in accordance with Federal regulations;

(4) Is on a motor vehicle route that crosses the CDNST, as long as that use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST;

(5) Is designated in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart B, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and:

(a) The vehicle class and width were allowed on that segment of the CDNST prior to November 10, 1978, and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST or

(b) That segment of the CDNST was constructed as a road prior to November 10, 1978; or

(6) In the case of over-snow vehicles, is allowed in accordance with 36 CFR Part 212, Subpart C, on National Forest System lands or is allowed on public lands and the use will not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the CDNST.”[42]

The CDT plan further adopts multiple use principals by clearly adopting management standards for motorized categories of the recreational opportunity spectrum and as a result the concept of an exclusively non-motorized corridor would directly conflict with the CDT plan. While the NTSA fails to specifically address multiple use trails along the CTD, the Management Plan does specifically provide that multiple use routes adopted under relevant travel management decisions shall be allowed and consistent with applicable planning. At no point in the CDT plan is the concept of an exclusionary corridor even mentioned.

The Organizations submit that while specific portions of the NTSA are less than clear when read in isolation or in an attempt to apply Wilderness or National Park type restrictions outside these areas, the NTSA is very clear in conveying the position that the CTD is truly a multiple use trail and that the CTD should not serve as a barrier to multiple usage of adjacent areas. The Organizations submit that creation of a landscape level buffer around the CDT, where multiple usage was prohibited or restricted would be a violation of both the NTSA and the CDT management plan. This should be avoided as there are significant challenges on the Rio Grande that are on a more sound legal basis and of significantly more important level to most forest users.

7d. NTSA management specifically requires a maximizing of economic benefits with is supplemented by relevant US Supreme Court rulings and Executive Orders mandate agencies balance management priorities based on the cost benefit analysis of the standard.

The implementation of a non-motorized Wilderness corridor around the CDT also gives rise to a wide range of issues when looked at from a cost-benefit perspective, which is made even more complex by the fact that the CDT runs through a wide range of lands, including public and private lands. The Organizations are also concerned that any heightening of the CDT management and a possible corridor around the trail as a management objective in the forest plan would be a difficult proposition when reviewed from a cost benefit analysis and against the maximization of multiple use benefits requirements of the NTSA.

The NTSA guidance is clear on issues involving equity and usage of NTSA routes and the need to balance multiple usage based on these factors based on economic returns associated with the management of the route. The NTSA explicitly provides as follows:

“(9) the relative uses of the lands involved, including: the number of anticipated visitor-days for the entire length of, as well as for segments of, such trail; the number of months which such trail, or segments thereof, will be open for recreation purposes; the economic and social benefits which might accrue from alternate land uses; and the estimated man-years of civilian employment and expenditures expected for the purposes of maintenance, supervision, and regulation of such trail;”[43]

While the Rio Grande has significant challenges facing all usage of the forest by the public, such as poor forest health, the CDT is a resource that is simply not used at a large enough scale by those seeking to exclude multiple uses to warrant directing extensive resources to revision of management efforts. A review of the Continental Divide Trail Coalition website reveals that approximately 2 dozen people traverse the entire CDT on an annual basis. [44] Unfortunately, this information is not broken down to more specific levels, such as usage of the CDT at state or forest levels. The Organizations can vigorously assert excluding multiple uses across a corridor for the benefit of as few as two dozen people is not maximizing economic and social benefits of these lands. Such as position simply lacks any factual basis.

As land managers are specifically required to compare the economic benefits of alternative uses of the trail and any possible corridor under both multiple use principals of planning and as more specifically directed by the NTSA, accurate economic analysis information is critically important to the decision making process. Given the fact that significant portions of the CDT are primarily used for recreational purposes, the comparative spending profiles of recreational usage is highly important information. It has been the Organizations experience that often comparative data across user groups is very difficult to obtain. The USFS provided such data as part of Round 2 of the National Visitor Use Monitoring process and those conclusions are as follows:

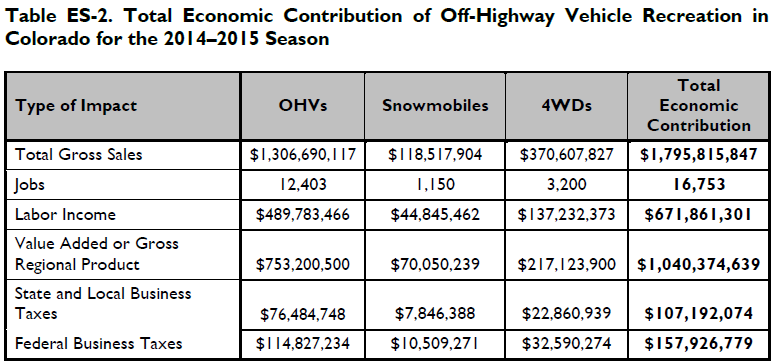

While the above agency summary data has become somewhat old, the Organizations simply don’t see any change in the comparative spending profiles of these users groups. The Organizations are aware of detailed research addressing certain portions of this analysis above. A copy of the most recent study of the Economic Contribution of the use of Off-Highway Vehicles in Colorado is attached to these comments. This analysis identifies a strong increase in the per person spending profiles of all user groups in the OHV/OSV community based on increased unit prices and new types of OHVs, such as side by side vehicles, being present in the marketplace.

The differences in comparative spending between the user groups allowed in a CDT corridor and those excluded from the corridor are stark and again simply do not favor designation of a landscape level corridor. When comparing the spending profiles of usages allowed in a proposed corridor such as hiking, primitive camping and cross country skiing to the usages that are excluded from the corridor, such as OHV use and snowmobile the disparity of spending profiles is stark. The users excluded from a corridor spend anywhere from 1.5x to more than 2x the amount of the user groups that would be allowed in the corridor.

As a result of the stark differences in spending profiles of the users, visitation of those allowed in any corridor would have to essentially double throughout the year in order to offset lost economic benefits from the users that would be excluded. This position and expectation is factually unsupportable as visitation to certain portions of the CDT by permitted users is limited to as few as dozens of visitors per year, while visitation levels from users possibly excluded is significantly higher than the visitation levels that are allowed within a corridor. As a result not only would corridor visitation have to double to offset lost users simply to break even on a per visitor days spending level but also the levels of visitation would have to massively expand as the levels of permitted corridor use is exceptionally low.

The Organizations do not contest that there are areas or attractions where the CDT sees very high levels of visitation but the Organizations are aware the areas of higher visitation are areas and issues that can be resolved at the site specific level in an effective manner and should not be relied on for the basis of a forest wide corridor. Additionally hikers of the trail are encouraged to visit local communities to the trail, which include South Fork, Pagosa Springs, Keystone and Breckenridge. The Organizations are unsure how a Wilderness like corridor can be reconciled with developed resources such as these large communities. Any attempt to resolve these issues would be exceptionally expensive from a management perspective and would result in user conflict. The Organizations must question if these areas and CDT issues more generally could not be more effectively managed through site specific planning subsequent to the RMP finalization. The Organizations submit that there are numerous diverse challenges facing the CDT, many of which are highly site specific, which should be dealt with at the local level rather than trying to craft a landscape level fix to these issues. There is simply insufficient levels of utilization of the CDT at the landscape level to warrant inclusion of such issues in the RMP.

7e. A Cost/Benefit analysis of corridor management must also be addressed.

In addition to having to balance economic interests in management of NTSA areas, both President Trump (EO 13771 in 2017) and President Obama (EO 13563 in 2011) have issued Executive Orders requiring all federal agencies to undertake a cost benefit analysis of management decisions. The US Supreme Court recently specifically addressed the need for cost benefit analysis as an issue and stated as follows:

“And it is particularly so in an age of limited resources available to deal with grave environmental problems, where too much wasteful expenditure devoted to one problem may well mean considerably fewer resources available to deal effectively with other (perhaps more serious) problems.”[46]

Given this clear statement of concern over the wasteful expenditure of resources for certain activities or management decisions, the Organizations are very concerned regarding what could easily be the wasteful expenditure of resources for the benefit of what is a very small portion of the recreational community.