USDA Forest Service

NEPA Services Group C/O Amy Barker

Geospacial Technology & Applications Center

222 West 2300 South

Salt Lake City, 84119

RE: Input regarding NEPA Streamlining process

Dear Ms. Barker:

The above Organizations welcome the opportunity provided in this comment period on how to refine and streamline the NEPA planning process and to provide more detailed information and input on our experiences with the NEPA process on a wide range of public lands in the hope that previous mistakes will not be repeated. The Organizations are providing these more extensive comments as we are aware that often the “why” behind a position that is taken is as important as the position itself. In these comments, the Organizations are targeting changes that can be undertaken in the planning process under the current legislative systems. While the Organizations support changes to the Legislative structure that governs planning, such as revising and updating the Endangered Species Act, the Organizations are also aware that such changes are outside the scope of the request from your Offices’.

Prior to addressing the specific concerns, our Organizations have regarding the NEPA process to date and streamlining of the process moving forward, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 2,500 members seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA currently has 2,500 members. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport.

The Off-Road Business Association (“ORBA”) is a national not-for-profit trade association of motorized off-road related businesses formed to promote and preserve off-road recreation in an environmentally responsible manner and appreciates the opportunity to provide comments on this issue.

The Idaho Recreation Council (“IRC”) is a recognized, statewide, collaboration of Idaho recreation enthusiasts and others that will identify and work together on recreation issues in cooperation with land managers, legislators and the public to ensure a positive future for responsible outdoor recreation access for everyone, now and into the future.

One Voice is a non-profit national association committed to promoting the rights of motorized enthusiasts and improving advocacy in keeping public and private lands open for responsible recreation through strong leadership, advocacy, and collaboration. One Voice provides a unified voice for motorized recreation through a national platform that represents the diverse off-highway vehicle (OHV) community. For purposes of this correspondence TPA, COHVCO, CSA, ORBA, IRC and One Voice will be referred to as “The Organizations”.

The Organizations are aware that the scope of NEPA review is heavily driven by federal legislation and as a result much of the statutorily required process is probably outside the range of discussion for the current request. As a result, the Organizations are focusing on guidance documents and principals related to the implementation of NEPA requirements for various projects and efforts. The Organizations submit that significant opportunities for a leaner and more efficient NEPA process are present as a result of the ambiguity in many of these guidance documents and related poor understanding of land managers in addressing many of the technical aspects of the NEPA process. These benefits are limited and any benefit of the streamlining process could easily be lost with implementation of processes that increase the administrative overhead of site specific projects or to the NEPA process as a whole. On the ground benefits of streamlining must be the goal of the proposal implementation.

1a. Public access must be the goal of any revisions to planning for recreational activity.

The Organizations are aware of several proposals in circulation that provide for certain NEPA streamlining benefits to accrue to only certain user groups or interests, such as outfitters or guides; or those that may be volunteering through a program similar to the Conservation Corps; or users of ski areas in off-season times of the year for the ski area. The Organizations are also aware of numerous proposals addressing veterans, holders of senior citizen pass or America the beautiful type passes. Often this type of reform is seeking to address only “facilitated access to public lands” and the Organizations must vigorously oppose this type of a revision.

While these are commendable efforts and programs, any NEPA streamlining should apply to all groups and efforts on public lands equally. Public lands should be available to all members of the public on an even playing field and when any group is elevated above the general public, this even playing field is lost. The Organizations are also aware that any efforts to prioritize a single group or category of users above the general public will result in a significantly more complicated planning process for land managers, as managers will now have to confirm the membership of the applicant in the prioritized group before moving forward. Simply keeping an up to date list of members in the group to be prioritized can prove to be a daunting task, regardless of if that membership is proved through a database held within the USFS or a membership card that is presented. The Organizations vigorously submit these are the types of streamlining efforts that must be avoided as resources will be directed towards tracking and managing the group rather than more efficient operations on the ground.

The Organizations concerns on this issue are two-fold:

- No user of public lands should have priority over other users in planning or permitting; and

- Tracking these groups will complicate any effort undertaken by land managers and run counter productive to the intent of the streamlining efforts.

1b. No new reports.

The Organizations vigorously believe that any efforts to streamline NEPA must avoid the creation of new reports, such as priority trails reports or landscape level reviews of possible national recreation areas. Too often efforts to streamline NEPA and other processes become bogged down with a desire to update or form reports on issues or challenges where the information needed for the decision making process is already available. The Organizations submit that examples of these concerns would be helpful. Any NEPA streamlining efforts must avoid reinstituting planning for areas that have recently completed a landscape level plan such as a Field Office or Forest Level plan.

The Organizations are aware of landscape level efforts within the BLM seeking to make planning more efficient, which has resulted in the formation of Landscape Conservation Cooperatives(“LCC”). These efforts highlighted the Organizations concerns regarding existing information being presented in a different report with different pictures or manner of presentation. The national LCC guidance brochure further provides quality examples regional standards that will not streamline local planning, as often the national LCC brochure provides information is in the form of somewhat random comments of DOI agencies that often do not relate to the goals and objectives of the LCC process. Examples of these comments include:

“Glorious fall foliage provides a backdrop for foraging Sandhill cranes.” [1] Or

“A majestic bull elk pauses for a drink in the southern Rockies.” [2]

These types of random statements are often highly frustrating to many partners and more properly suited as a note to a picture in a travel brochure rather than part of a mission statement for meaningfully undertaken landscape planning that will result in effective and efficient management of issues on the ground. The Organizations assert these efforts fall well short of seeking best available science and a more dynamic and streamlined planning process with expanded collaboration of the public and partners, even if the statements are largely symbolic. If regional planning is undertaken, the goals for regional planning must seek to obtain higher quality regional documents than are currently being provided.

Further numerous comments in the national LCC brochure attribute issue specific statements to agencies that are completely unrelated to that agency’s mission or expertise. An example of such a quote would be the following quote attributed to NOAA:

“Preserving cultural artifacts and traditions creates vibrant, healthy communities.”[3]

While NOAA is an impressive organization that does great work, NOAA’s expertise is not in cultural resources and the Organizations must question any decision that sought to rely on NOAA in such a capacity. There are a wide range of true partner organizations that have long histories of effective management of this issue, such as state historic preservation offices and the national register of historic places, and failing to rely on these organizations for their expertise may complicate partnerships with them in the future.

The Organization would question any value in a report addressing the maintenance backlog on public lands. This is a known quantity already and any further reports on this issue must be avoided as it would be drawing resources away from on the ground efforts to address maintenance backlogs. Any efforts on streamlining NEPA must focus on “on the ground” benefits that can be achieved, such as streamlining NEPA for existing facilities or routes rather than developing additional planning or analysis efforts.

1c. Identification of priority trails must also be avoided.

The Organizations must oppose any attempt to create a list of priority trails for maintenance as part of a streamlining proposal and believe there are many more factors to be balanced in the identification of priority trails for maintenance then could ever be addressed with a national list. Given the large number of routes that are not being maintained to acceptable standards, the Organizations must question the value of only identifying a small number of trails nationally that are to receive elevated maintenance. It has been the Organizations experience that land managers in small planning areas can easily identify a small number of trails on their district that need heavy levels of maintenance. The Organizations must question the value of identifying a national list of priority trails for maintenance, as the limited resources of land managers will be not fully utilized for maintaining trails at the local level but will be directed to developing the national list.

If priority trails are to be identified for expanded management, the Organizations submit that numerous additional factors must be balanced in the identification of priority trails for maintenance. One additional factor should include leveraging of resources available from partners for the maintenance of the route now and for the foreseeable future. The Organizations submit that the long term financial sustainability of any priority routes that are identified must be reviewed, as maintaining a trail in the short term that has no additional sources to insure the long-term usage of the route simply makes little sense. Insuring the long term financial sustainability must be addressed in any review process to ensure that resources directed to a priority route or area in the short term are not lost in the long term for many of the same factors that might have placed the route on the list in the beginning.

When identifying priority maintenance routes, the basic sustainability of the route must be addressed, as many routes simply are not in ideal locations for maintenance. Often routes are in locations for reasons other than the recreational usage of the area, such as routes in creek beds and routes that have been placed due to historical usage of the areas by pack animals and wildlife. Identifying priority trails for maintenance should not omit questions such as: “Is the route in a sustainable location?” or “Does the route make sense from a cost/benefit analysis?”.

3a. Recreation permitting process must be reviewed.

Over the past three decades, the permit application process seeking approval for smaller events on public lands has become unpredictable and so costly that the average American has to either break the law or do something else. The Organizations are interested in a simple, consistent and cost-effective application that is realistic in its approach to the permitting process. The process should provide for equal opportunity on all federal land, whether the applicant is a large for-profit corporation or a small volunteer not-for-profit.

The Organizations submit that a far more refined course filter/fine filter type of review must be developed in order to make permitting processes more understandable and effective in the NEPA process. Our concerns can generally be outlined with the following issues:

- Application of permitting requirements has to be consistent on all public land;

- The current “Hand Book” for permitting of events on public lands needs dramatic revision; Clearly identifying that previous environmental analysis developed for permits should remain the basis for the issuance of categorical exclusions for the event unless there is a significant change in the event;

- Complete outline of any independent monitoring;

- Review of “Cost Recovery” and insurance qualifications must be addressed. Guidance should clearly identify that:

- costs associated with the event operation, such as lodging outside federal lands or food provided to participants is a deductible expense when calculating revenue from events for permitting applications;

- Providing a 3% cap of the adjusted gross revenue of the event cap on permit costs; and

- Explicitly provide a waiver of cost recovery provisions under specific conditions.

- Streamline “Volunteer” and “Cost Share “agreements; and

- Set reasonable timelines and institute an event analyses. High Country can’t get a permit to groom longer than a year because the insurance company will not issue a certificate for more than a year.

The permitting process and related NEPA can make simple projects with strong long-term partners far more complicated and the Organizations submit that some of these issues can be resolved with more clarity in guidance documents surrounding permits. We are providing three examples of projects events where permits and associated NEPA have become major challenges. While the examples of the beacon checkpoints and grooming have been resolved and operations are continuing but resolution has taken significant time and effort to resolve and the local office response to these projects has been highly variable. The Organizations have to believe these types of efforts can have a significant impact on resources of any office when resolving these types of concerns are tallied. While two of the three examples have been resolved too often the club type social events simply are not occurring.

The first example involves the placement of beacon checkpoints by local snowmobile clubs at winter trailheads to: 1. recommend to the public the use of avalanche beacons in areas where avalanches are a high concern; and 2. Remind the public to turn their beacon on before going into the backcountry. The checkpoints are reflected in the following pictures:

Colorado Snowmobile Association has placed more than 2 dozen of these beacon checkpoints throughout the state, and is pleased to report that in some locations in the state land mangers immediately saw the value of these efforts and placement was smooth and seamless. These managers were aware that club liability insurance and existing grooming permits covered signage and moved forward with little additional review. Once these checkpoints were in place, community response was overwhelmingly positive and benefitted all users of these areas, which the Organizations submit are exactly the types of projects USFS managers should be partnering to achieve in the most effective and streamlined manner possible.

About half of the clubs placing these signs had a very different experience, where land managers had concerns about liability from admitting there were avalanches in the area, advertising of businesses identified as project partners on the signage; and a possible need to undertake some level of NEPA or issuance of a specific permit for the sign. While these concerns were eventually resolved, the process was slow and often painful for the volunteers attempting to place the sign. These issues were compounded when one club has a beacon checkpoint sign up for a year or two on one side of a pass while the club on the other side of a pass, which is managed by a different office, does not have the same sign placed due to concerns over NEPA and permits slowing the process. The amount of administrative time allocated to these requests in offices moving forward with additional review must have been significant.

Our second example of NEPA and permitting requirements greatly complicating providing services to the public involves the issuance of SRPs for winter grooming. In Colorado all winter grooming is provided through a partnership with our Colorado Parks and Wildlife Program and local snowmobile clubs. The CPW program provides grants to purchase groomers and partial funding for operation of this equipment, which is then leveraged with volunteer operators and huge levels of community support. Each club obtains an SRP for their grooming operations through their local forest service office. For many clubs this is a reasonably streamlined process and permits are provided on a multiple year basis.

However, this experience is not universal as we are aware of a club that must apply for an SRP on an annual basis. The reasoning for an annual SRP being required is simply astonishing and represents a prime example of where a poorly streamlined process can significantly impact on the ground benefits. The basis for the annual permit is the fact the local club cannot get proof of insurance for their operations for more than one year. The Organizations believe a comparison to other long-term obligations that require insurance is highly valuable. This is simply astonishing as this type of issue could easily be resolved with a multiple year permit that simply required insurance be in place, as is the norm for residential mortgages. The residential borrower simply has to keep insurance on property as part of the mortgage and without insurance the mortgage is fully due. Without such provisions, the residential mortgage market would simply not exist. The Organizations are unsure why additional proof is necessary for these grooming operations.

Our third example is probably the most common by a large margin and involves streamlining of the NEPA/permit process to address challenges faced by those hosting smaller socially based not for profit type events. It has been the Organizations experience that too often small events, such as trail rides of a limited number of OHV’s (sometimes groups as small as 5 vehicles) organized through a local club on designated routes or county roads crossing federal public lands are prohibited due to the fact that land managers believe a permit is required for the event. Often this management position is taken based on the small fee collected for the event in order to off-set direct costs of the event such as food provided on the event or facility rentals (such as town parks or similar facilities) where a social function such as a barbeque is provided after the event is concluded. Smaller types of events are great ways for new residents of a geographic area to connect with people that are familiar with the challenges and opportunities that the area provides and allow for these new residents to access these locally available and exceptional recreational opportunities in a safe and responsible manner.

An example of this situation will provide context for our concerns. Frequently local clubs meet on an evening during the week and members may identify a desire to meet at a particular trailhead or parking lot later that month and run a particular trail and end the day at a particular restaurant or pavilion in the town park for a barbeque. It is not uncommon for a particular member to stop and grab a value pack of burgers, some chips and soda at the local market so when people stop for lunch the meal is enjoyable and more social. Normally a hat gets passed as part of this process and everyone attending throws in $10 towards lunch and maybe rental fees on a pavilion or back room at the end location for the event. The funding from this type of an event is simply comically insufficient to support any type of NEPA analysis and imposition of even an administrative fee will probably be cost prohibitive due to the small number of attendees, who may very well be on the forest individually that weekend.

The Organizations are aware that often far too much weight is placed on these small fees obtained to offset direct costs of the event. These fees were never intended to create a profit for the club that might be organizing the event but are merely put in place to supplement club dues that may not be of sufficient amount to cover the supplies that are being provided for the event. Often for events of this small size, the permit cost and associated NEPA simply exceeds any costs that could reasonably be paid by an attendee and far exceeds any other costs incurred for such an event and as a result, the events simply don’t occur. When the permit costs and efforts to obtain the permit are broken down to a per user cost, the cost is simply horribly out of reach for those that would like to attend the event. This is often highly frustrating to members of the public, who simply don’t understand why a permit is even required for the event.

The Organizations also believe that streamlining permits for small not for profit organizations will improve relationships between these Organizations and land managers, which is of growing importance to the future of the forest service. Many of these local clubs that are facilitating these impromptu events, are also a major source for volunteer labor now being sought to supplement diminished agency budgets and often these small local clubs are a major source of funding for projects. In some states, federal land managers must partner with clubs in order to obtain grants and other private funding is only issued to organizations with particular tax status, such as the §501© designations frequently held by clubs. Overly strict permitting requirements for non-profit events frequently impairs the interest of the local clubs to partner with land managers for grants or other support in the future. These benefits are critical moving forward and will also be difficult to place an exact monetary value on as well.

3b. The scope of permit streamlining efforts should be expanded to allow for full inclusion of federal land management agencies involved in event permitting.

The Organizations are aware that often recreation permits are issued involving a wide range of smaller federal lands managers beyond just the US Forest Service. Often these smaller land management agencies provide a crucial, albeit smaller role, in an event occurring. Such a case would be when a permit for a 100-mile event route is issued and 95 miles of the route is on USFS lands but a critical 5 miles is needed to connect the loop for the event occurs on lands managed by another federal agency, such as the Bureau of Land Management or Bureau of Reclamation. The Organizations are active participants in the annual “King of the Hammers” race event in Southern California and are aware that the event occurs primarily on BLM lands but a small portion of the event route crosses the 29 Palms Marine Base. As a result, permits for the King of the Hammers event must be provided by the Department of Defense in conjunction with the BLM. The Organizations would note that only partially streamlining the permit process with respect to land management agencies for these types of cross border events on federal lands would hinder the benefits of any reform. The limited streamlining of permitting may lead to a large amount of frustrations from permit applicants as what is a small portion of the lands necessary for the event to occur being the more difficult to obtain permits for the event on.

The Organizations are not directly familiar with the specific permitting process of these other land management agencies, but would become concerned if any streamlining efforts within the USFS would need extensive revision to encompass these management agencies as streamlining of the permit process is somewhat time sensitive as well. The Organizations believe that a complete revision of the streamlining efforts may not be necessary to embrace these smaller land management agencies as we believe providing the voluntary “opt in” to the streamlined permitting process on a case by case basis. This voluntary “opt in” type streamlining may allow for a streamlined permitting process without opening the entire permitting process for these agencies if there was significant conflict in these other agencies permitting process.

3d. Timely issuance of permits for events can be difficult.

The Organizations are also aware of numerous situations where permits for events simply cannot be issued in a timely manner due to a wide range of issues surrounding the permit issuance. Frequently many small events are simply not thought of months or years in advance but are more of informal nature and may only be organized at a club meeting a month or two in advance and this type of event development is completely at odds with a permitting process that often requires at least an 18-month lead time for a complete NEPA review of permit applications at an EA or higher level of review. While these events may be less formal in nature, these events provide important recreational opportunities to those that are participating in the event. Often these small less formal events simply cannot be planned more than 18 months in advance and do not have the resources to undertake extensive review of possible impacts for what are existing routes and facilities. Often event coordinators simply don’t pursue the event due to the barriers that are presented by the permitting process, which is unfortunate at best and a major barrier to access to public lands at worst. This is an area where streamlining of NEPA can assist.

Timing of permits is also complicated by factors outside the direct permit issuance and these are often related to the timing restrictions of insurance coverage for the partnership. An example of this problem would be highly valuable. In Colorado, the majority of winter grooming on Forest Service lands is provided through local snowmobile clubs with the issuance of a special management permit for the grooming by various districts. Each of the local clubs pools insurance costs through the state association and collectively purchases insurance for these operations at a significantly reduced cost. While many USFS offices understand the limitations of insurance coverage to one year in this situation and issue multiple year permits with a requirement that insurance coverage remain in place, we are also aware of offices that simply will not issue multiple year permits due to the limitation of insurance coverage and policies to one year.

Rather than simply requiring insurance coverage be maintained under a multiple year permit, both the land manager and volunteer club representatives must apply for a new grooming permit every year. If this policy was applied to the purchase of homes, the public would not be able to obtain a 20 or 30-year mortgage to purchase a home but would rather have to renew their mortgage annually after providing proof of homeowner’s insurance. Clearly this issue has been resolved outside of public lands, and continued issuance of annual permits simply makes no sense and would highlight a situation where a streamlined process would assist both managers and volunteer partners on public lands.

4. Fees charged for permits are often unrelated to actual permitting costs.

The Organizations are also aware of numerous events where the permitting costs simply exceed any reasonable costs for the administration of the permit, which creates unnecessary conflict between users and land managers. In certain instances, these unduly large permit application costs preclude the event from ever happening and in other instances these large costs are simply passed through to event participants, and as a result events on public lands can cost more than if the event had occurred on adjacent private lands. Neither of these situations is acceptable to the Organizations and in certain circumstances these large fees have created the possible public perception that certain groups are charged certain fees and other groups with similar events are charged a lesser fee and that these decisions are made in a somewhat arbitrary manner by the deciding official. Avoiding these types of issues should be of paramount importance in the permitting process.

The Organizations submit that often the public perception of these large event permit costs is that the permit revenue is being used a profit center for that office or land management agency to offset overhead costs to the office for operations that are unrelated to the permitted event. While the Organizations often partner to assist in offsetting operational costs, the Organizations also firmly believe that permitting of activities should not be a profit center for land managers, as this is simply a violation of the trust placed in these managers by the public. Avoiding even a perception of such a situation should be a major priority in the streamlining of the permit process.

5. Existing partnerships would be repaired with a streamlined permitting process.

The Organizations believe the streamlining of the permit process would help repair partnerships between federal land managers and local Organizations, as often the same local club that is not allowed to undertake an event due to permitting issues is a major source of both volunteer labor and partner funding for the land management agency. Forming these types of partnerships can be difficult and stressful for volunteers and the failure to obtain permits in a timely and cost-effective manner can simply provide unnecessary stress on this relationship. The Organizations are aware of federal land managers requiring a permit for a club event involving less than 10 street legal motorcycles using a route entirely on county roads due to the fact that the riders might stop at a parking area adjacent to the county road to use a bathroom facility on BLM lands. This request created amazing stress on the partnership between the Club and the land managers as the Club holding the event was also the Organization spearheaded efforts in obtained all funding for the construction of the parking lot and restroom facilities through a state OHV grant several years prior. While this example occurred on BLM lands, situations like this are far too common on USFS lands as well. A streamlined permitting process would be a significant step towards resolving these types of challenges and hopefully relieve burdens and possible conflicts in the future as all permits will be provided in a more timely manner.

6. Organizational liability must be addressed in addition to volunteers.

As part of recent Forest Service efforts to expand partnerships for recreational maintenance type projects, not for profit Organizations are now being asked to undertaken more and different types of maintenance projects than ever before. This is very concerning as USFS volunteer agreements and Cost Share Challenges do address individual liability but fail to include a limitation on organizational liability for volunteer groups that are working on stewardship projects on public lands. With the expansion of partnerships as a resource tool for federal land managers, NPO will be expanding partnership projects with land managers and they should be clearly protected in these situations.

Liability can easily result for the Organization when zealous volunteers may not be familiar with the scope of the insurance coverage in place or there are issues that arise out of up to date training for volunteers. We frequently encounter this issue when an NPO has BD&O or general liability coverage in place to undertake a project but the scope of the project with the USFS encompasses projects that are believed to be maintenance by some and construction by others. An example of this situation would be a club being asked to replace a damaged, vandalized, removed or end of life span sign along a trail. While some will look at replacing this sign as maintenance, as the sign was there and is being maintained under a volunteer agreement and probably covered under a general liability policy, other interested parties will see this as new construction, which should have been the basis of some type of cost share challenge agreement and at least an endorsement on the general liability policy. Volunteers frequently lack the technical insurance savvy to even understand the concern and possible liability in this grey area, as commonly a “well versed” volunteer can identify what the policy for the club cost and maybe the term of the policy. It is highly unlikely that any club representative will understand the scope of coverage and related limitations of their coverage.

This type of grey area liability is a huge concern for the Organizations as we are aware of several state level partners who have been sued in these situations for projects on state lands. Several of these Organizations were defended under insurance that was in place but the Organizations failed to survive the lawsuit, such as the experiences of the Nebraska Off Highway Vehicle Coalition. Often these defenses for NPOs are undertaken without clear language in the policy and the Organizations are concerned that at some point this type of coverage will not be provided to the not for profit partners. This is the type of ambiguity that will eventually result in liability to an NPO and every effort should be taken to minimize risk and avoid this situation.

We are aware of several clubs that have undertaken stewardship projects on trails on federal public lands and after consulting in detail with their general liability insurer, were either entirely dropped from future coverage renewals or were provided with quotes that were entirely out of reach for the club. Many of these quotes exceeded $10,000 per year for the club as insurers were treating the project in a manner similar to construction of a major interstate highway rather than repair of a trail on federal public lands. While clubs can cover small insurance requirements, these are volunteer organizations with limited resources to cover insurance. With insurance expenses of this size providing a clear immunity type protection to the federal budgets, as the Organizations are aware that any savings from insurance costs would probably be directed into stewardship donations for projects the club may be undertaking that year. With the large levels of volunteer organizations doing this work, this cold easily develop into significant new funding for land managers.

Another club undertook annual stewardship projects, ranging from periodic trail maintenance to the purchase of maintenance equipment in partnership with land managers after obtaining grants from the State OHV program. This club was obtaining project specific insurance riders on their general liability insurance policy for each stewardship project. Issues subsequently arose when sufficient documentation regarding the land managers acceptance of the completed projects could not be obtained despite the projects being completed according to the project specifications. Staff for these acceptance reviews was simply not available. After several of these riders could not be satisfied, the insurer was forced to cancel any further insurance coverage based on the perception that liability was resulting to the club due to failure to perform projects in a manner acceptable to land managers. This simply was not the case but without documentation this conflict was difficult to resolve. With the expansion of club immunity to these types of projects would avoid these challenges to partners.

While the Organizations are aware this issue will only be truly resolved with an amendment to existing federal legislation, the Organizations appreciate this opportunity to raise this concern and seek any assistance that might be able to be provided.

7. Planning efforts should strive to remain consistent with the scope and objectives of the Process.

In the development of any planning efforts, maintaining the scope and goals of the planning effort is critical as the planning effort moves forward, as often planning efforts can drift away from the original goals and objectives of the plan. This issue is of more significant concern in larger planning efforts, as often when landscape level planning efforts drift away from the original intent of the process new directions for the effort are embraced to address issues that are outside the scope of the original proposal. Public support for efforts is sought to be expanded by seeking to address numerous localized issues when the primary driver of planning may drop in value or concern. With this project drift, the public is not properly engaged and there are numerous collateral impacts such as the project now addressing artificially inflated management issues in the planning process.

The Organizations were actively involved in development of the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (“DRECP”) which sought to streamline the permitting process for large renewable energy development projects in landscape sized sections of the California desert area. While we are aware this project primarily addressed BLM managed lands, it provides a good example of project drift. A significant driver of the DRECP project was high oil prices in the marketplace when the planning efforts commenced. As the DRECP process moved forward, oil prices receded and other smaller scale priorities were elevated, often with minimal research or analysis, in an attempt to maintain political support for the project. The Plan that resulted was only marginally related to the original goals and objectives of the project and addressed a wide range of local decisions that were outside the scope of the original project. The end result of the project was a Plan that was roundly criticized and was opposed by almost all local communities involved and businesses that were originally intended to be beneficiaries of the effort.

Planning efforts must strive to address challenges that can actually be addressed at the scale of planning being undertaken and avoid directing resources towards artificially elevated planning issues. Any planning efforts must be meaningfully undertaken, avoid taking what are largely symbolic gestures on issues, avoid making local site-specific decisions at the landscape level and insure that the final regional plan is a high-quality document that meets the original goals and objectives of the regional planning efforts. This may mean that planning efforts should be stopped and this position can be difficult for local or regional planning staff to undertake and explain internally, especially when there are interested parties seeking to move forward with goals outside the scope of the original project.

8. Revisions should streamline and clarify the applicability of Categorical Exclusions and other lower levels of NEPA for projects.

Any NEPA revisions must streamline and clarify the applicability of Categorical Exclusions and other lower levels of NEPA for projects, in order to provide consistency in the decision-making process while reducing costs and speeding the resolution of management challenges. These challenges generally fall into two major categories: 1. Situations where a single project or event crosses multiple planning boundaries or involve multiple agencies which can result in inconsistent analysis or decisions between districts for the same project; and 2. Similar projects are often analyzed differently based on target audience of the project, such as lower levels of NEPA being required for a heavily used bicycle trail while more NEPA analysis is often required to address a minimally used multiple use trail. While this can be defended based on guidance currently in place, this application simply makes no sense on the ground and clearly results in increased costs and reduced partnership opportunities.

With the high rate of transition among field staff, this clarity in guidance will also avoid significant changes in NEPA necessary for a particular project with a change of staff in the office. These mid- process changes often result in conflict between partners and delayed resolution of issues with higher costs and may put partner funding obtained under strict timelines into jeopardy simply due to the revised NEPA timelines. An example of this concern is again helpful. Many times, when recreational trails are crossing wetlands or other riparian areas, these crossing areas need periodic maintenance and this periodic maintenance provides a good example of where streamlining would be very helpful. Some land managers will see this as a wetland or riparian restoration that can clearly be done with a Categorical Exclusion, while other managers will see this type of project as a trail construction issue and require at least an EA. If a staffing changes occur in the middle of the project, the project may basically stall until the higher level of NEPA is satisfied and all the while the resource damage continues to occur. This would be a prime opportunity where clarity in management requirements would streamline the process significantly and insure that any partners engaged in the process are not lost and that partner funding simply does not expire waiting for NEPA to be completed.

It has been our experience that when there are multiple agencies or jurisdictions involved in the planning process, any lack of clarity in the Planning Rule or implementation documents results in higher levels of NEPA being applied to the Project. This results in significant additional time and resources being directed towards analysis of the project rather than resolving the management issue on the ground. Any new planning rules should encourage managers to look at any issue in the manner that requires the least amount of NEPA analysis. This is an issue where planning rules and subsequent guidance handbooks can provide a significant opportunity to streamline and provide line officers with an identifiable agency position that allows the project to move forward and not get bogged down in NEPA analysis.

9. Guidance should encourage planners to recognize that federal planning may not be effective for all challenges.

The Organizations are aware that often there is significant public pressure on land managers to enter into planning efforts in response to a wide variety of pressures or concerns, some of which can be resolved in planning and others of which are motivated by a desire to appear responsive on issues. Any NEPA streamlining must provide the ability to local land managers to allow a decision not to move into planning in response to a challenge.

As highlighted in recent Greater Sage Grouse planning, habitat management was a major planning challenge and was directly impacted by high levels of quality habitat being on private lands adjacent to public lands. Often public lands habitat was of significantly lower quality in a large number of planning quadrants. In many Sage Grouse planning quadrants, Grouse habitat areas were located more than 50% of the time on private lands adjacent to public land and as a result, planning efforts required collaboration at much higher levels than planning that only addressing public lands. Managers should be allowed to recognize this issue and rather than reenter NEPA planning, simply work collaboratively with private land owners as habitat management was often an issue outside the scope of federal authority.

10a. Implementation of the minimization criteria in subsequent rounds of planning must be clarified.

Guidance around the NEPA process could significantly streamline implementation of the minimization criteria provided for in the Travel Management Rule,[4] when new planning efforts are adopted. Under the minimization criteria, possible resource impacts from roads and trails are to be minimized, while allowing managers to achieve the management objectives for each area identified in the relevant Resource Management Plan for the Forest. This issue is becoming more common as many Forests are approaching the end of the normal life spans for Forest Resource Management Plans created in the first round of forest plan development. Absent an intervening act, such as an ESA species listing, Wilderness or SMA Congressional designation, previous minimization analysis may remain highly relevant for significant portions of federal lands and would essentially create a presumption that existing activities in conformity with the existing plan would continue to be available under the new Resource Plan being developed. In contrast any argument that minimization must be undertaken completely and without regard to the planning in place lacks factual credibility as most forest plans we work with have clearly identified minimization goals and objectives in place and often fully implemented over the life of the plan. If the goals have not been achieved managers should be confident in their decisions to lessen minimization goals to achieve the plan objectives rather than have to defend against those seeking to tighten access to public lands.

Providing guidance to local managers that minimization does not need to be fully reviewed at the forest level with each round of RMP development when there are not significant changes in the forest plan goals and objectives for the area would streamline planning and NEPA review. Areas that will continue to be developed under higher levels of usage will continue to have high intensities of roads and trail, while backcountry areas will have less. While a forest plan revision may adjust small portions of boundaries for these areas, a landscape level alteration of these general goals and objectives is simply not probable or realistic. Management clarity on the relationship of existing minimization and ay minimization review in any new planning effort would allow managers to more extensively review minimization in areas that management goals have significantly changed and avoid directing resources to area without significant changes in the goals and objectives of the area.

Too often extensive pressure is applied on land managers by those opposing a particular usage to minimize all possible impacts from an activity on the forest without regard to planning history in a portion of the forest.[5] Often this pressure is provided in the form of compelling summaries of partial summaries of court decisions or management decisions from the National Park Service, which operates outside multiple use requirements of the US Forest Service. The Organizations must question any asserted relevance of management decisions taken by agencies outside multiple use requirements to the decision making process for agencies governed by multiple use requirements.

The Organizations submit that there is a limited factual relevance of the minimization criteria to most second round Resource Management Plan development efforts at the forest level unless there is a significant change in management or an intervening Congressional action such as a Wilderness or Special Management area designation. Most management plans do not significantly alter the goals and objectives for management of large portions of the forest and as a result resource impacts should remain consistent with the goals of the management area and not be heavily impacted by artificial needs to minimize resource impacts. Levels of usage and routes will simply be higher around a developed campground or urban corridor when compared to a Research Natural Area and any assertion to the contrary would lack factual basis. Land managers should be provided with clear management direction addressing the need to recognize the complete management history of the area, and the basic consistency of management objectives across planning processes to avoid issues in reapplying the minimization criteria that most forest planning resolved in the first round of planning. Minimization simply was never intended to be an ongoing process without regard to the goals and objectives established in the Forest Planning process and implementation of guidance recognizing this factual reality could again significantly streamline the NEPA process.

10b. Management direction for areas adjacent to National Trails System routes must be clarified to streamline NEPA.

The management of areas adjacent to routes identified under the National Trail System Act, such as National Scenic or National Historic Trails, has recently become another issue where clear agency guidance could significantly streamline the NEPA planning process. Existing agency guidance currently asserts that motorized vehicle use by the general public is prohibited on these routes, which simply is not accurate and directly conflicts with the clearly stated intent and provisions of the National Trails System Act. The Organizations do not contest that motorized usage is prohibited in Wilderness areas, Research Natural Areas or national wildlife refuges but would also note that there are significant portions of the National Trails System Act that specifically recognize multiple usages on trails outside those areas and identify the need for planners to maximize benefits and minimizing conflicts in areas adjacent to any trail identified in the NTSA. As an example of how clear guidance will streamline NEPA is the fact that almost 20% of the Continental Divide Trail is currently located on motorized roads and fails to identify how many miles of motorized trails are currently co-located on the CDT. Such a factual situation is functionally impossible to exist if current NTSA guidance was accurate.

As a result of this incomplete and inaccurate current guidance, local land managers are now at least forced to provide an alternative in NEPA analysis that addresses the complete closure of these corridors to motorized usage. Again, this is another issue were incomplete summaries have been provided previously and then subsequently significant public pressure is being applied based on the incomplete summaries. Providing accurate guidance on this issue would narrow the scope of questions to be resolved any NEPA process involving areas around a route designated under the NTSA.

10c. Roadless areas managed outside National Roadless Rule.

Both Colorado and Idaho have promulgated state level roadless rules that are outside the scope of the 2001 National Roadless Rule and both of these Roadless Rules have moved towards higher intensity management and wider scopes of usage of Roadless Areas when compared to the National Rule. Both State Roadless Rules have recognized the need to manage poor forest health of these areas at a higher level than were previously addressed in the 2001 Roadless Rule. While these rulemaking efforts have been completed for several years, the differences between these state rules and the national rule have not been fully integrated into the planning and inventory process guidance from the USFS. The failure to fully integrate these new rules has complicated NEPA implementation on both Forest and District level efforts undertaken subsequently.

While timber sales and road construction were identified as primary change factors in Roadless areas, these factors are often now seen as critical factors in establishing basic forest health and protecting recreational usage, water quality. While the 2001 Roadless Rule never altered multiple use requirements for management of these areas, there was immediately inferred a strong relationship between Roadless Areas and future Wilderness designations in much of the USFS management guidance. This relationship is at best questionably relevant nationally with the explosion of forest health issues since final release of the national Roadless Rule and even less relevant in states that have completed promulgation of their own roadless rules which clearly identify the need for timber management and multiple use of Roadless areas in those states.

The basic direction and intent of these state planning efforts is significantly different in addressing these activities now found necessary, but that were originally found to be the major activities to be avoided in Roadless areas. While these state Roadless Rules have been formalized for extended periods, no national guidance has been provided to inform local planning efforts regarding the different direction and scope of these rules in relation to active management. Rather all inventory process move forward under the premise that there is still a similar level of desire to move Roadless areas to Wilderness, which is directly contradictory to the direction and intent of both the Colorado and Idaho Roadless Rule. As part of a NEPA streamlining process, proper guidance should be provided regarding the different direction and intent that Colorado and Idaho have promulgated in their Roadless Rules. These are different guidance and inventory standards and these differences must be reflected in guidance documents.

10e. Recommended Wilderness Areas must have management clarity.

For many of the same reasons as Roadless Area management could be streamlined in Idaho and Colorado, the inventory and management of Recommended Wilderness areas could be significantly streamlined as well. Too often land managers feel compelled to expand Recommended Wilderness areas in the management process and to subsequently manage these areas to improve their Wilderness suitability. The Organizations are aware that often those seeking expansion of these types of designations make a compelling presentation in meetings asserting a need for more Wilderness and that often Wilderness is the solution for pretty much any management challenge. It has been the Organizations experience that often these presentations simply lack factual basis and often lead to significant management changes in these areas, such as prohibiting dispersed recreation on trails, forest health treatments and other activities that the USFS has successfully balanced for decades in the areas now sought to be designated as RWA or similar. Our concerns about lost opportunities for dispersed recreation are compounded by the fact that until such time as Congress designates an area as Wilderness it is to be managed for multiple use under federal law.

Two concerns highlight this need for management clarity on RWA and related management standards and these concerns are: 1. Public lands are a finite size and the odds on finding new Wilderness like areas is slim after the numerous inventory and planning efforts that have been undertaken to date; and 2. The ability of land managers to actively address the poor forest health now systemic on public lands is impaired by Wilderness like designations applied in the planning process. The first concern is simply factual in nature and based on more than 50 years of inventory and review of possible Wilderness designations as part of the Forest planning efforts. The odds on any manager finding a new Wilderness area on a Forest is slim, especially given the increased visitation to public lands that the USFS is struggling to continue to address and manage. At this point, most new Wilderness areas identified have resulted from restrictive management practices in the past or the failure of current managers to understand the extent of previous inventory undertaken. Most NEPA analysis the Organizations have participated in fails to recognize the previous inventory process and related conclusions of these inventories. Sometimes this problem arises from the fact that the local land manager was in Junior High School when the first rounds of the RARE process were being undertaken. They simply have no personal knowledge and must be educated about the long and intricate history. This is where the streamlining opportunities are presented, as many land managers are not able to locate detailed reports and other information conducted around possible RWA or Roadless areas previously.

Many of these possibly new Wilderness recommendation areas were found unsuitable for designation as Wilderness decades ago, and the reasons were identified in those inventory documents. Unfortunately many times these documents are not readily available or have not been transferred to a modern format for use by managers in current planning efforts. The Organizations submit it is no more acceptable to close a non-conforming usage in subsequent planning than it was to close the usage at the time of the original inventory. Such an occurrence is simply too frequent and has again happened in the Great Burn RWA on the Nez-Pierce/Clearwater NF in Idaho, where motorized usage was lost due to a perceived need to manage these areas to improve Wilderness characteristics despite these areas never being suitable for designation previously and often these areas having a well documented history of multiple usage.

In addition to managers lacking a complete inventory history for areas, which makes closure decisions easier, managers frequently are subjected to significant pressure to the effect that Wilderness improves forest health and protects wildlife. This position again lacks any factual basis as the poor forest health is the single largest challenge that will face land managers in this generation. As a result of pressure and poor facts, managers are forced into poor decisions that impair addressing poor forest health rather than streamlining planning requirements and subsequent site specific efforts. Resource Management Plans should be asking how do we address dead tree removal and streamline restoration of landscapes to protect water resources and recreational opportunities by restoring forest health in future. Instead Resource Management plans and expanded Recommended Wilderness designations often make addressing these issues more difficult.

The relationship of poor forest health and heightened restrictions on management of public lands has been repeatedly addressed by the USFS researchers but much of this information is simply not well know to planning officers. In a Rocky Mountain Research Station report reviewing the USFS response to the bark beetle outbreak, management restrictions were clearly and repeatedly identified as a major contributing factor to the outbreak and a major limitation on the response. This report clearly stated:

- Limited accessibility of terrain (only 25% of the outbreak area was accessible due to steep slopes, lack of existing roads, and land use designations such as Wilderness that precluded treatments needed to reduce susceptibility to insects and disease).[6]

- In general, mechanized treatments are prohibited in designated wilderness areas. The Arapaho Roosevelt, White River, and Routt National Forests in Colorado have a combined total of over one million acres of wilderness; the Medicine Bow National Forest in Wyoming has more than 78 thousand acres. A large portion of these wilderness acres have been impacted by the current bark beetle outbreak.[7]

- Owing to terrain, and to budgetary, economic and regulatory limitations—such as prohibitions on entering roadless areas and designated wilderness—active management will be applied to a small fraction (probably less than 15%) of the forest area killed by mountain pine beetles. Research studies conducted on the Sulphur Ranger District of the Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest help us understand the implications of this situation.[8]

With clear management concern regarding the impacts of restrictive management on the pine beetle response, the Organizations must question any restrictions on active management of forest health issues from expansion of these types of recommended Wilderness like management designations.

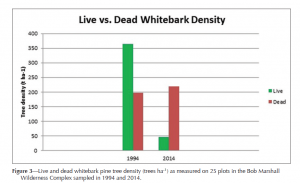

Many other researchers are now recognizing the negative impacts of Congressionally designated Wilderness on Forest Health and the ability to manage these areas in response to the challenges presented by the changing climate of the planet. In a review of pine blister impacts to forests in the Bob Marshall Wilderness area, researchers again concluded that the

Again these areas were much more heavily impacted than adjacent areas where management had been more active in nature. Given the clearly negative relationship between heightened management restrictions in any area and more rapid and severe impacts to forest health, the Organizations must express serious concerns regarding any management in the new RMP that made addressing forest health issues more difficult. It entirely lacks a basis in science and good management policy.

10e. Subpart C implementation guidance must be issued to streamline subsequent NEPA.

The Organizations have been significantly involved in the litigation and subsequent rule making efforts around implementation of the over the snow portions of the Travel Management Rule as a result of the Idaho lawsuits in both 2011 and 2017 and legal challenges to the California grooming efforts on USFS lands. Our support for the need for expanded guidance on the implementation of the OSV Rule is further based on our experiences with implementation of the new USFS planning rule. After involvement in these efforts the Organizations submit that these are issues were future NEPA efforts could be significantly streamlined with the issuance of guidance documents by the USFS leadership to local offices. While this guidance documentation would not directly address NEPA, this guidance would clearly address numerous issues surrounding the NEPA process, such as when is existing planning sufficient to move forward with issuance of an OSVUM, and educating managers there is no deadline for the issuance of an OSVUM if planning is less than complete. It has been our experience that there is significant confusion around the OSV planning issue currently with line officers.

Our experiences working with local managers undertaking forest plan revisions after issuance of the USFS Planning Rule 2.0 and before issuance of agency implementation guidance documents weighs heavily in our position on the need for OSV guidance materials to be developed. Often local managers became overly cautious on issues as a result of the lack of national guidance and undertook reviews that were simply unnecessary since there was no guidance available for these planners to rely on when developing a new forest level plan. At best these overly cautious decisions lead to additional levels of public reviews and what can only be a FAR more extensive internal agency process being undertaken in an attempt to dot every I and cross every T. Often times these new processes and reviews lead to confusion of the public regarding a wide range of issues such as: 1. The scope of what was and was not open for comment in the planning process; 2. When next steps in the planning process were going to be undertaken; and 3. Conflicts between the planning process undertaken on planning units within immediate geographic proximity as some forests dealt with issues in one step while other forest broke a process down into multiple elements. This lead to confusion and frustration of the public and some of the public simply disconnecting from planning efforts moving forward. Guidance documents from USFS leadership recently issued have seemed to help with this issue.

An example of the overly cautious planning efforts that have resulted from the lack of national guidance on how to implement USFS planning 2.0 requirements can be found on the GMUG national forest in Colorado. Here planners provided a far more extensive comment process in the Wilderness Inventory phase of planning that ever before, in the hope of complying with the new transparency and public involvement portions of the Planning 2.0 efforts. As a result public comments were accepted regarding the suitability of the entire landmass of the GMUG for possible Wilderness recommendations.

While the Organizations are aware such a review is technically required under the Wilderness Act and related planning regulations, the scope of public comment was unprecedented on the GMUG as comments were accepted on the entire forest and on new issues such as boundary adjustments in the inventory process. Most planning efforts previously have inventoried the entire landmass of the forest but only accepted comment on areas that at least arguably met the criteria for possible inclusion in the Wilderness after a preliminary review by land managers. Involving the public in Wilderness inventory process so much earlier than ever before appeared to be based on a lack of clarity around implementation of Planning 2.0. The Organizations are concerned that this lack of clarity in the planning process implementation has probably degraded the quality of public involvement in the process, lead to some confusion of the public in commenting and created work for planners, both as a result of the added process and the need to respond to public input that will probably be confusing at best. While the Organizations appreciate the caution and transparency of the process, we are also not sure this level of transparency is necessary and submit this would be a situation where guidance could be very helpful in streamlining future NEPA processes. The Organizations submit that implementation of the OSV rules should not suffer from these types of confusion that resulted from delayed national guidance around the implementation of Planning 2.0.

Our concerns regarding a lack of national guidance documents addressing OSV travel is even more acute with implementation of OSV planning as this is an entirely new process for winter travel management and has been evolving as a result of the various lawsuits. This litigation has fueled the rumor mill regarding what is and is not required in planning. Most planners had a working knowledge of USFS planning process before Planning 2.0, but any of the planners we have spoken with lack even this type of basic working structure for OSV travel. While there have been areas and forests that have previously embarked on winter travel specific plans, such as the White River National Forest (WRNF) in Colorado or the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit (LTBMU) around Lake Tahoe, California, most planners we have contacted are simply unfamiliar with the planning requirements, scope of lawsuit settlement and are expressing a generally confused position on OSV management and implementation. National guidance would be very helpful in developing high quality NEPA in the future and avoiding litigation of OSVUM that might not be based on high quality planning efforts or forest plans that are out of date, such as happened with the second round of litigation in Idaho in 2017. These types of guidance documents would be even more valuable for planning efforts as there is no mandated completion date for OSV travel management under the litigation settlement, which is a very different direction than most planning efforts and certainly implementation of the summer portions of the travel management process.

Implementation of OSV planning has moved forward under three general categories:1. The LTBMU, WRNF and others have moved forward with independent separate landscape level winter travel plans; 2. Other forests have moved forward with winter travel planning as part of forest planning; and 3. Other areas have moved forward with Winter Travel on a very site specific level, such as that occurring on Rabbit Ears and Vail Pass areas in Colorado. National guidance on the factors that were weighed by land managers and impacted how these land managers identified the proper level to move forward under would be helpful for planners that are embarking on OSV planning for the first time. Basic information and guidance on questions such as:

- Would these land managers repeat the OSV planning at the same geographic level or would they change the scope of their efforts?

- What hurdles were encountered during implementation of their plan?

- What planning tools have well and what issues or challenges could be addressed more accurately or completely in planning in the future?

These are the kinds of basic challenges that land managers appear to be addressing around OSV travel and the experiences of planners on the WRNF and LTBMU and others would prove very insightful on landscape level decisions. The fact that the LTBMU is now moving forward with their second round of OSV planning on the basin provides even further opportunity to leverage the experiences on this unit and further refine planning on other units. The LTBMU provides opportunities to address questions like how has the previous vigor in planning on the LTBMU influenced the direction and scope of the second round of winter travel review being currently undertaken on the LTBMU on issues such as minimization factors.

Guidance from the national office could address experiences with more detailed questions or proposal in the planning processes at the forest or local level. Several of these existing OSV plans efforts have also relied on planning criteria that were interesting at the time the plan was developed but either failed to be valuable for a variety of reasons. Examples of this would include:

- Relying on altitude as a trigger for winter planning as attempted by several forests as part of the California grooming settlement;

- The WRNF attempting to include tree density as a planning factor in OSV planning.

Guidance should be addressing why the altitude floor as a trigger failed in the California discussions and that while the WRNF tree density issue was interesting, it has proven to be less than relevant to the planning efforts. The WRNF experience has been that many in the snowmobile community frequently are now seeking out areas foresters thought were unrideable and with the ever evolving technology and hybridization of the OSV travel many of these more densely treed areas are now the most desirable for snowbikes and hybrid skiers. Conveying this type of experience would be highly valued in any national guidance.

In addition to the more specific OSV planning experiences identified above, the Organizations believe any guidance from the summer travel planning process would also be helpful. From the Organizations standpoint our experiences with local travel planning were always more successful than larger landscape level planning efforts for travel. Local planning for travel simply allowed better public involvement, issue identification for specific routes, and better public buy in to the planning during the implementation process as the public understood why decisions were made. Too often the public was completely overwhelmed by the scope of identifying specific routes in landscape planning for more than 1 million acres, priorities were directed to certain areas of the forest while other important areas received and this generally resulted in lower quality public input being received.

The Organizations area aware of situations where landscape level travel and site specific planning were being undertaken at the same time, which has led to awkward issues and fostering of distrust between users and managers for inadvertent oversights. This resulted in local planning being completed immediately before the release of landscape level analysis and then landscape level planning omitting routes to be build or opened in the site specific efforts, despite the route being a priority in the site specific planning. While these failures were resolved eventually in the landscape level efforts, the identification and resolution of the issues were awkward at best and did not improve relationships between land managers and the public.

Additionally it has been the Organizations experience that landscape level planning for travel results in simply too many issues of scale. Often maps lack clarity such as basic landmarks or are relying on boundary lines that are unclear or cover a large a large corridor simply due to the scale of mapping needed to cover millions of acres. Too often questions at the route specific level, such as a route being inside or outside a certain planning designation are complicated by a map boundary covering a corridor of hundreds of feet on the ground. This is a major concern when that boundary makes or breaks the existence of a route that is only 50 inches wide but beloved by a community.

Conclusion.

The Organizations welcome the opportunity provided in this comment period on how to refine and streamline the NEPA planning process and to provide more detailed information and input on our experiences with the NEPA process on a wide range of public lands in the hope that previous mistakes will not be repeated. The Organizations are providing these more extensive comments as we are aware that often the “why” behind a position that is taken is as important as the position itself. In these comments, the Organizations are targeting changes that can be undertaken in the planning process under the current legislative systems. While the Organizations support changes to the Legislative structure that governs planning, such as revising and updating the Endangered Species Act, the Organizations are also aware that such changes are outside the scope of the request from your Offices’.

The Organizations are aware that the scope of NEPA review is heavily driven by federal legislation and as a result much of the statutorily required process is probably outside the range of discussion for the current request. As a result, the Organizations are focusing on guidance documents and principals related to the implementation of NEPA requirements for various projects and efforts. The Organizations submit that significant opportunities for a leaner and more efficient NEPA process are present as a result of the ambiguity in many of these guidance documents and related poor understanding of land managers in addressing many of the technical aspects of the NEPA process. These benefits are limited and any benefit of the streamlining process could easily be lost with implementation of processes that increase the administrative overhead of site specific projects or to the NEPA process as a whole. On the ground benefits of streamlining must be the goal of the proposal implementation.

If you have questions please feel free to contact either Scott Jones, Esq. at 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont, CO 80504. His phone is (518)281-5810 and his email is scott.jones46@yahoo.com or Fred Wiley, ORBA’s Executive Director at 1701 Westwind Drive #108, Bakersfield, CA. Mr. Wiley phone is 661-323-1464 and his email is fwiley@orba.biz .

Scott Jones, Esq.

COHVCO & IRC Authorized Representative

CSA President

Fred Wiley, ORBA President and CEO

Authorized Representative of One Voice

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

[1] See, Department of Interior, Landscape Conservation Cooperatives Brochure – undated at page 3. available at http://lccnetwork.org/Media/Default/Misc/LCC_brochure_web.pdf

[2] See, Department of Interior, Landscape Conservation Cooperatives Brochure – undated at page 1. available at http://lccnetwork.org/Media/Default/Misc/LCC_brochure_web.pdf

[3] See, Department of Interior, Landscape Conservation Cooperatives Brochure – undated at page 2. available at http://lccnetwork.org/Media/Default/Misc/LCC_brochure_web.pdf

[4] See, Executive Order 11644 as amended.

[5] See, https://wilderness.org/sites/default/files/legacy/Travel-Analysis-Best-Practices-Review.pdf or https://wilderness.org/sites/default/files/ORV%20Minimization%20Criteria%20White%20Paper—May%202016.pdf as examples of the pressures applied on managers to minimize without regard to management history or goals and objectives for the management area and to rely on Park Service guidance for basic management direction on multiple use lands.

[6] See, USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station;” A review of the Forest Service Response: The Bark Beetle Outbreak in Northern Colorado and Southern Wyoming prepared at the request of Senator Mark Udall’: September 2011 at pg i. (Hereinafter referred to as the “Udall Forest Health Report”)

[7] Udall Forest Health report at pg 5

[8] Udall Forest Health Report at pg 18

[9] Retzlaff, Molly L.; Leirfallom, Signe B.; Keane, Robert E. 2016. A 20-year reassessment of the health and status of whitebark pine forests in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, Montana. Res. Note RMRS-RN-73. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 10 p.