The 2024 Sweepstakes is officially on!

Enter NOW to win this amazing Moto Adventure Package!

Enter now! Trails Preservation Alliance

All volunteer 501c3 organization, focused on preserving motorized, single-track trail riding.

Trails Preservation Alliance

All volunteer 501c3 organization, focused on preserving motorized, single-track trail riding.

Enter NOW to win this amazing Moto Adventure Package!

Enter now!

Senator Perry Will

200 East Colfax RM 346

Denver, CO 80203

Senator Dylan Roberts

200 East Colfax RM 346

Denver, CO 80203

Representative McLachlan

200 East Colfax RM 307

Denver CO 80203

Representative Mauroa

200 East Colfax, RM 307

Denver CO 80203

RE: SB 24-171 Wolverine reintroduction in Colorado

Dear Senators and Representatives:

The above Organizations would like to express our support for the above legislation but are concerned that the Legislation does not provide enough protections for the public from unintended impacts from the reintroduction of the Wolverine. We have been very involved in the decades of discussion around possible reintroduction of wolverines in Colorado and management efforts for other species after they were reintroduced, such as the Canadian Lynx. As a result, we are intimately familiar with the need for legislation, such as SB 24-171, to avoid unintended impacts from the reintroduction. We are also unfortunately intimately familiar with the long and twisted history that the status of the wolverine has had on the Endangered Species Act. The Organizations vigorously support the concept that ranchers should be paid for any lost revenue they experience as part of a wolverine reintroduction.

The Organizations are all too familiar with assertions of the need for management of species based on possible sighting, which has too frequently driven lynx management efforts long after their successful reintroduction. The Organizations would like to avoid this situation being repeated with the wolverine. We are concerned that there are many other concerns and possible impacts of the wolverine reintroduction that are not addressed in SB24-171. While we support SB 24-171 we also would ask for additional protections for recreational activities on public lands that might be temporarily occupied by wolverines. This protection would reflect the dual mission of CPW to manage recreation and wildlife. The Organizations are aware that recreational activities have often immediately identified as risk to the wolverine despite decades of research being unable to identify any relationship between wolverines and recreation.

Our concerns on possible unintended impacts have been the basis for extensive efforts previously that are not currently addressed by the USFWS. The Organizations were active participants in collaborative efforts to address possible wolverine reintroduction that involved CPW, USFWS, CDOT, Colorado Ski County, Colorado Cattlemen Assoc. and many others in the 2010 to 2013 timeframe. (“2010 Collaborative”). This was a massive effort spanning several years and included in person meetings attended by sometimes more than 40 people. We have attached a list of attendees from the December 2010 meeting as an example of the diverse range of interested groups that participated as Exhibit “A”. We have also attached a sample of the meeting notes and issues summary from these meetings as Exhibit “B”. While this was a large CPW collaborative effort, awareness of the entire effort was marginal at best. It is disappointing that many of the priority issues around wolverine reintroduction identified in this CPW collaborative were simply not addressed in the most recent listing decision for the wolverine by the USFWS. Even more disappointing is the fact CPW simply did not address these concerns in their comments, despite many of these management designations, such as a 4d designation and 10j rule being hugely necessary. Our collaboratives also included designations of Candidate Conservation Agreements and Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances. The Organizations are thrilled that 24-171 makes these efforts mandatory.

The 2010 Collaborative effort led by CPW went as far as developing a draft reintroduction plan for the wolverine in Colorado. We have also attached a copy of the draft plan developed by CPW for your convenience as Exhibit “C”. It is disappointing that none of these issues and concerns were even raised by CPW in their most recent comments on the 2023 listing proposal and science update. In the 2013 USFWS listing the Service specifically stated there should be no change in forest management decisions, as a result of the wolverine being present. We have attached a copy of the USFWS 2013 listing document that clearly states this in the highlighted portion of page 2. A copy of this document is attached as Exhibit “D”. This type of protection would be hugely valuable to the recreational community if it was included in the reintroduction plan for the wolverine.

We are aware this is an usual letter of support for any piece of legislation and appreciate your engagement on this issue. We are aware this issue is highly complex and nuanced and are very concerned that CPW has not engaged on the most recent discussion on the wolverine. Rather than CPW taking a collaborative path as they did in previous discussions, collaboration has been avoided in the most recent discussions. The Organizations and our partners remain committed to providing high quality recreational resources on federal public lands while protecting resources and would welcome discussions on how to further these goals and objectives with new tools and resources. If you have questions, please feel free to contact Scott Jones, Esq. (518-281-5810 / scott.jones46@yahoo.com) or Chad Hixon (719-221-8329/Chad@Coloradotpa.org)

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

CSA Executive Director

COHVCO Authorized Representative

Chad Hixon

TPA Executive Director

Marcus Trusty

President – CORE

We’re thrilled to announce that the TPA 2023 Annual Report is ready for your perusal! Your steadfast support has been instrumental in advancing our mission, and we extend our heartfelt gratitude.

Thank you for being an essential part of our journey. We invite you to explore the accomplishments and milestones detailed in the report, all made possible through your invaluable contributions.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Attn: Jody Kennedy

Via Email at jody.kennedy@state.co.us

RE: 2024 SCORP Development Effort

Dear Ms. Kennedy:

Please accept these comments from the Trail Preservation Alliance regarding the development of the new Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP).

The Trails Preservation Alliance (TPA) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization focused on preserving Off Highway Motorcycle (OHM) recreation. The TPA takes the necessary actions to ensure that Land Managers including Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) achieve a balanced amount of access for OHM recreation on public lands. In addition, the TPA is active in education and outreach and supporting the establishment and operation of regional off-highway motorcycle clubs.

We have actively participated in the development of the previous version of the SCORP and have been supporting participants in CPW led efforts such as Partners in the Outdoors conferences, the OHV Grant program, and others. We are aware of the success that the SCORP has had in addressing issues such as providing solutions to historically limited funding sources. While these new funding sources are significant, they have targeted uses that were traditionally underfunded. This situation has changed over the last SCORP’s life and now non-motorized recreation is disproportionally provided funding exceeding that of both the motorized and snowmobile programs combined. As a result, we would ask for equity in the allocation of new funding sources. While the OHV and snowmobile registration programs have provided immense amounts of funding for decades, it was not the intention of these programs to become the sole funding source for multiple-use trails.

Our constituent and supporters have been actively engaged in CPW programmatic efforts such as scoring hundreds of OHV grant applications with the CPW trails committees and actively participating on many other committees and subcommittees. Our engagement has also expanded in the last five years with many of the newly formed Regional Partnerships across the state (e.g., Pikes Peak Outdoor Recreation Alliance, Envision Chaffee County, NoCo Places, etc.). Our constituents have also actively partnered with the USFS and BLM offices and staff to perform a wide range of services around trails that benefit all users including cutting trees that block trails, teaching new employees how to operate equipment, hiring maintenance crews to address site specific problems, addressing new challenges such as people living on public lands and post fire disaster restoration efforts.

We have embraced addressing many new challenges facing the State, however we cannot overlook the fact that in some regions of the state interests are badly divided and often simple challenges become highly political or overly confrontational. It seems we are departing from a long Colorado history of dealing with challenges collaboratively. These impacts have been witnessed in CPW public meetings where CPW representatives are observed preemptively disconnecting communication with a member of the public while making comments on the transparency of agency processes. We are concerned about the impacts and message this sends – volunteers could become less willing to volunteer or partners may direct funding elsewhere when recreation is not prioritized equitably. We request that the SCORP seek to address this as a challenge moving forward. Just as many of our partners are now champions for the motto of “be nice – say hi” on the trails, this motto ought to be embraced in both CPW meetings and recreational projects more now than ever before.

While multi-use motorized single-track is our passion, our ability to pursue this passion is substantially underrepresented, comprising only 8% percent of all trails in the state. The TPA has endeavored diligently to address motorized recreational access issues with the development of a self-funded statewide strategic plan. The Colorado Off Highway Motorcycle Trail Opportunity Plan (COTOP) was developed for the OHM community to graphically portray current opportunities, identify strengths and weaknesses of those opportunities, highlight where land management strategies are favorable for OHM recreation and suggest where opportunities might be improved upon. The alignment of COTOP, the SCORP development and CPW restructuring should not be overlooked or ignored. Upon your request, we would gladly share a copy of this visionary strategic plan for your reference.

In the interest of cooperative collaboration, the TPA would like to raise another suggested issue for the SCORP to address, which is the staffing challenges that are faced by both CPW and Federal land managers. While staffing has always been a difficult issue in many parts of the State, we have seen this become an almost unresolvable challenge very quickly. This has presented immense problems as too many positions with our CPW and Federal land manager partners are simply going unfilled.

As a result of these barriers from staffing, the motorized community has taken what is virtually an unheard-of step to understand basic components of the staffing challenges. It has been our experience that we need to clearly understand problems before they can be solved, and the motorized community has also developed research to try and address basic barriers to hiring. We were leaders in attempting to understand if hiring challenges were isolated to federal land managers or if it also encompassed state managers. Were similar challenges seen in the private sector or is this disproportionally in the public sector? Was the Youth Corp seeing similar challenges in hiring their crews? Many wanted to simply increase salaries, but those that have increased salaries have not seen major improvements in hiring and retention. Many thought this hiring barrier was a lack of awareness of federal positions, which resulted in a federal hiring blitz over the last two years. Once again, if you are interested, we will provide you a copy of this research.

Even those existing positions that are being filled are being filled by employees that often lack the experience, skills and even a basic understanding of the decades of efforts that have resulted in management accomplishments to the level where they are today in the state. Rather than celebrating these preceding successes, such as wildlife populations being at or above goals in the State, we too often hear wildlife populations are collapsing or that travel management has not occurred from many new federal and state employees. Often this erroneous narrative is coming from groups that neither support the agency nor recognize even the most basic tenants of public lands management such as the multiple-use mandate. This is creating immense conflict and stopping desperately needed projects from moving forward, such as expanding recreational infrastructure in the State. For far too long we have simply assumed there would be a sufficient supply of these opportunities and in many areas, this is now proven to be an incorrect assumption.

We thank you for this opportunity to comment on the SCORP. We believe the SCORP should guide CPW through its upcoming revisions in structure and provide a vision for the newly created recreation division within CPW for the next several years.

Respectfully,

Chad Hixon

Executive Director

Trails Preservation Alliance

Members of the Senate Agriculture & Natural Resources Committee

Via Email Only

Re: Concerns regarding CPW Commissioner Confirmations

Dear Committee Members:

Please accept this correspondence as the statement of the significant concerns of the above Organizations regarding the upcoming confirmation of the Governor’s nominees for Commissioners on the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission (CPW). The above Organizations have partnered with CPW for more than 50 years through the voluntarily created Off Highway Vehicle (OHV) and Snowmobile Registration Programs that CPW administers. These Programs currently are providing more than $8 million per year in funding for all forms of recreational opportunities across the State. This funding directly provides more than 60 crews to support designated routes.

The Organizations are concerned that these appointees simply do not meet statutory requirements for appointment and will not bring balance to CPW but rather will continue to be overly focused on particular species and issues unrelated to recreation. This lack of a demonstrated experience in the nominees is critical to balance within CPW and the Commission as all the nominees are being nominated for recreationally-based seats on the Commission.

Over our 50-year partnership, our relationship with CPW has ebbed and flowed. It is with this perspective, our Organization’s can say CPW is simply out of balance and this imbalance is probably the worst we have ever seen. Right now, there is no one with dispersed recreational experience on the Commission despite 83% of Colorado residents participating in trails-based recreation. The economic contributions of outdoor recreation to Colorado recently reaffirmed by the US Department of Commerce when they found more than $14 Billion Dollars of economic contribution to the State and 14,000 jobs in 2022 alone. While the Outdoor Industry has a designated Office tasked with representing them, primary management of the users of outdoor recreational opportunities is vested within CPW. All we are asking for is skilled representatives on the Commission to fulfill this critical need to represent recreational users. It is frustrating that issues such as this must be addressed.

Balance within CPW has been difficult since the merger of the historical Division of Parks and Division of Wildlife on July 1, 2011. The failure of the old Division of Wildlife and Division of Parks to merge operations was specifically identified as an ongoing concern in the investigation of Director Prenzlow’s comments at the Partners in the Outdoors event in 2022. While we understand wolf reintroduction has placed unprecedented and unexpected stress on CPW, we must also recognize imbalance was there before wolf reintroduction. Our concerns about balance within CPW has only grown further with announcements that the reintroduction of the wolverine is now going to be pursued. Reintroducing another species is concerning given the under representation of recreation during wolf reintroduction which reintroduction remains less than complete on the ground. We are very concerned that adding another species to this discussion will only result in recreation being further under valued within CPW.

It is important to note that our discussions have always been cordial with CPW staff but we have consistently found these discussions to be of limited impact. Too often we have been told, either directly or indirectly, that recreation was simply not a priority right now. These types of prioritizations of staff has resulted in CPW sometimes being unresponsive to significant concerns of the recreational community despite our 50-year partnership and millions in annual funding. Recent efforts that highlight the failure to prioritize recreation would include:

Issues such as this within CPW are becoming far too common and we believe are the result of CPW simply not properly weighting recreation concerns in their operations. While these are somewhat technical issues and concerns within CPW, they are critical to the long-term success of CPW’s recreational efforts. These are also issues we must ask why our Organizations are leading discussions and efforts to address. Should we partner with CPW on issues like these? Yes. Should we lead these efforts? Maybe not. It is from this position, we are asking for strong experienced leaders for recreation on the Commission.

The Organizations are concerned that the current list of nominated CPW Commissioners have little to no recreational background. Our concerns are compounded as the nominated Commissioners will be the entire recreational voice on the Commission as all recreational-based commissioners were not reappointed. We are aware that the critical role that CPW plays in nonconsumptive recreational activities throughout the State is often poorly understood by the public. The Commission was designed to address issues like this and ensure the mission of CPW is achieved on all issues.

As an example, the winter grooming program is a perfect example of how complex the relationship of State and Federal partnership efforts can be. Most of the public thinks the more than 3,000 miles of winter grooming is provided by federal managers. This is incorrect. Some of the public understands grooming is provided through a local nonprofit club that is largely volunteer. This is somewhat correct. Even fewer understand the critical role that CPW trails program plays in this effort. We would submit that Commissioners must understand these types of efforts within CPW if they represent recreation. Living next to a State Park or temporarily managing a State Park in another State is simply insufficient experience to warrant an appointment to the CPW Commission. These appointments address impacts and policies for programs like ours. The Organizations vigorously assert that the current nominees will not address the imbalance within CPW’s two missions, but rather will continue or expand the existing imbalance as they have minimal background in recreation.

CRS 33-9-101(3) requires CPW Commissioners to have a demonstrated reasonable knowledge of issues when they are appointed, and this statutory requirement is more important than ever before for CPW. We can say with certainty that this standard was a major concern when this provision was passed as part of the legislation for the merger of DOW and Colorado Parks. Commissioners must be experienced leaders that assist CPW leadership based on their experience in the field of recreation, not merely people who could be trained over some period of time to meet the legal requirements for appointment. If this was the standard for appointments, why have a standard at all? While the new Commissioners may be generally concerned about wildlife issues, this does not mean they are knowledgeable leaders in the field of recreation. Experience and expertise must be demonstrated when they are confirmed not years after confirmation.

Our general concerns around the failure of nominees to demonstrate recreational expertise started with the Commissioners who are stepping down from the Commission in 2024. Many of these outgoing Commissioners lacked a strong recreational background when they were appointed. Largely these Commissioners were trained over the several years by CPW staff and partners. Our members volunteered to support these trainings in order to educate the Commissioners on the massive amount of effort and collaboration already occurring within CPW. It is frustrating that none of these Commissioners were even proposed for reappointment for reasons that are unclear. We would like to avoid spending years more of staff and volunteer time and resources to train new Commissioners who appear to be even less qualified than the Commissioners who are stepping down. While we will support this type of training again, we are also concerned that this is time and resources that CPW no longer has to direct in this manner.

The Organizations are thrilled with the CPW announcement of efforts to realign its operations to create a recreation and lands department within CPW. This would be a major step forward in prioritizing recreation within CPW and balancing the two goals of CPW. We are aware that reorganizations such as this need strong experienced leaders on the Commission to support CPW staff to be successful. Our experiences with the merger of Parks and Wildlife have proven this need. Strong experienced Commissioners will allow them to identify challenges and problems with new policies and staffing levels such as the challenges we have noted previously. Being a value-added resource to CPW staff on trails issues such as those we noted previously is not accomplished when Commissioners must start with education that CPW addresses issues on federal lands and has a Trails Program. The ability of skilled and experienced commissioners to share experiences around programs will be a resource during the reorganization and this type of collaboration will avoid problems in the future. Effective management and operations will expand support for CPW and their staff, which will be more necessary than ever if multiple species are to be reintroduced at the same time. Commissioners must be a resource to CPW rather than a drain and despite the best of intentions unskilled commissioners will be a burden.

The need for experienced recreational leaders on the Commission is further exemplified by the staffing shortages that are systemic with CPW and Federal lands managers. These staffing shortages are highly evident in the recreational community. The existing expertise of the staff has diminished greatly as many federal offices are only at 50% capacity and many of those staff are in an acting role. How can we lead discussions on training needs for new staff at CPW or USFS/BLM when Commissioners need to be trained. The simple answer is we can’t.

The Organizations are very concerned that the Commissioners seeking confirmation lack the necessary qualifications for appointment. While these nominees may be qualified in fields close to recreation and be passionate about wildlife issues this is not a demonstrated knowledge of the important issues discussed above. Could the nominees be trained over the next several years? Of course. We have tried this previously and failed to retain those Commissioners. We are asking the Senate to take a hard look at the qualifications of the nominees to the CPW Commission. CPW is facing unprecedented challenges to the recreational portion of its mission and strong experienced Commissioners will be a critical component of meeting these challenges.

The Organizations and our partners remain committed to providing high quality recreational resources throughout the State while protecting resources. We would welcome discussions on how to further these goals and objectives with new tools and resources. If you have questions, please feel free to contact Scott Jones, Esq. (518-281-5810 / scott.jones46@yahoo.com) or Chad Hixon (719-221-8329/Chad@Coloradotpa.org).

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

CSA Executive Director

COHVCO Authorized Representative

Chad Hixon

TPA Executive Director

Marcus Trusty

President – CORE

BLM Colorado State Office

Attn: Big Game Corridor Amendment/EIS

Denver Federal Center, Building 40

Lakewood, CO, 80225

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the vigorous support of the Organizations for Alternative A of the Draft RMP Amendment and EIS for Big Game Habitat Conservation for Oil and Gas Management in Colorado (“the Proposal”). The Organizations are unable to identify any Alternative that arguably applied multiple use concepts or recognizes the huge success of existing management in protecting wildlife. Every other alternative proposed also mandates the application of the mile per mile route density for oil and gas routes but expands the scope of routes that could be impacted to every route in a wildlife corridor as definitions are not provided for oil and gas related activities but are provided for action that are clearly unrelated to oil and gas. As an example, the Proposal fails to define or address in any manner equipment that is commonly found in the development of oil and gas wells, such as loaders, bulldozers, graders and other heavy equipment. While equipment such as this is not included the Proposal is able to include definitions of oil and gas issues uses such as boating, mountain bikes and other activities that could not be more unrelated to oil and gas in any way. We simply have been able to understand how and oil and gas route could be identified or how the mile per mile density was developed. We are not able to find any meaningful discussion of how this standard was established.

The Organizations are deeply troubled that the entire Proposal appears to be nothing more than an effort to build a cap-and-trade program for public access to public lands. As we have noted previously, the Proposal suffers from many foundational problems that are only compounded when analysis of the Proposal is addressed from that perspective. While the recreational community may not be opposed to the concept of a cap-and-trade system on public lands, the Proposal is so poorly developed and defined that meaningful discussion cannot be achieved. As a result, we are vigorously opposed to the implementation of the Proposal in this manner as the recreational community has almost nothing to gain in terms of expanded opportunities but has everything to lose if the Proposal is not accurately developed and successfully implemented. When we must identify the fact that none of the management agencies currently has the legal authority to do most of what they are proposing, we think this entire process will be a significant negative impact to all forms of recreation in the State.

Prior to addressing the specific concerns, the Organizations have regarding the Proposal, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 250,000 registered OHV users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations. The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a largely volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite the more than 30,000 winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport. CORE is an entirely volunteer nonprofit motorized action group out of Buena Vista Colorado. Our mission is to keep trails open for all users to enjoy. For purposes of these comments, TPA, CSA, CORE and COHVCO will be referred to as “the Organizations.”

The motorized community is the only recreational group who has been legally required to balance recreational opportunities with wildlife protection for more than 50 years. Over this 50-year span, we have worked hard to proactively address wildlife needs in conjunction with recreation, and until very recently we had been informed these efforts had been a successful partnership of interests and in most areas of the state, populations were well above goals for the species. Our Organizations have also become the single largest partner with land managers in funding sustainable recreational opportunities on public lands across the state.

The Organizations are VERY concerned about the exceptionally poor nature of the Proposal analysis of issues as 100% of motorized and non-motorized recreational opportunities are at risk of closure in the Proposal. This unprecedented impact of the Proposal is specifically identified as follows: [1]

Given that recreation in the state of Colorado provide more than $11.5 billion in economic contributions that provides more than 125,000 jobs to Colorado citizens[2] the Organizations would submit possible impacts to these significant benefits must be addressed. Despite the massive benefits to Colorado from outdoor recreation, the fact that 100% of motorized and nonmotorized routes has been proposed to be subject to a mile per mile density cap is simply never meaningfully addressed.

The Organizations do welcome the inclusion of the grandfathering of existing travel management decisions in the Proposal. This is a minor step in recognizing the effects and benefits of current management. This minor step simply does not address the massive long-term impacts that the Proposal has on all recreational access as the Proposal hugely expands the number of uses that are subject to the mile per mile cap and fails to recognize that most uses have never undergone any type of management. This will result in massive conflict between users and huge unintended impacts to uses totally unrelated to oil and gas.

The Organizations would like to believe this decision was made to protect and balance recreational uses, but we are forced to believe this grandfathering is based on another concern. This concern is the failure of the Proposal to identify a model for implementation of the goals and objectives for the effort that can ever be implemented. AS we outline subsequently, basic definitions of critical terms are not provided and the factors that are reviewed simply are unrelated to travel management. When these criterial are applied to any planning area, it becomes immediately apparent there are catastrophic failures in the analysis. Rather than dealing with these issues, the Proposal simply pushes those failures into the future in the hope these failures can be dealt with in the future.

The Organizations provided extensive comments in scoping on a wide range of issues, none of which appear to have been addressed. As a result, we are resubmitting those concerns as part of these comments to preserve legal options on the Proposal. These concerns are not reproduced here simply to avoid the submission of repetitious information.

The development of the Proposal has been based on a broken legal foundation from its inception as the Proposal has been based on the input of Organizations that simply are no more than managers of certain portions of the BLM multiple use mandate. While Wildlife may be a significant issue for these agencies, this does not alter the fact that the agency is only managing a small portion of a much larger management requirement. The specific identification of wildlife as part of the multiple use mandate is clearly identified as follows:

“(8) the public lands be managed in a manner that will protect the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource, and archeological values; that, where appropriate, will preserve and protect certain public lands in their natural condition; that will provide food and habitat for fish and wildlife and domestic animals; and that will provide for outdoor recreation and human occupancy and use;[3]

This management of wildlife as part of the multiple use mandate of public lands is again clearly stated as follows:

“(c) The term “multiple use” means the management of the public lands and their various resource values so that they are utilized in the combination that will best meet the present and future needs of the American people; making the most judicious use of the land for some or all of these resources or related services over areas large enough to provide sufficient latitude for periodic adjustments in use to conform to changing needs and conditions; the use of some land for less than all of the resources; a combination of balanced and diverse resource uses that takes into account the long-term needs of future generations for renewable and nonrenewable resources, including, but not limited to, recreation, range, timber, minerals, watershed, wildlife and fish, and natural scenic, scientific and historical values; and harmonious and coordinated management of the various resources without permanent impairment of the productivity of the land and the quality of the environment with consideration being given to the relative values of the resources and not necessarily to the combination of uses that will give the greatest economic return or the greatest unit output.”[4]

The protection of wildlife is an important use of public lands, but this is not an absolute requirement on BLM lands, but rather is one of many factors that must be balanced. While State agencies involved in this effort are addressing only a single portion of the multiple use mandate, this does not absolve the BLM from balancing all factors required in federal public lands. This balancing of factors simply has not occurred as after reviewing the Proposal we are entirely unable to understand the scope of the Proposal or how it will relate to existing management decisions and various Congressional designations. The failure of the relationship of the Proposal to existing management could not be more exemplified by the fact that at no point 4.2m acres of Roadless Areas, more than 3.5m acres of Congressional of Wilderness and extensive other areas where mineral withdraw is entirely prohibited.

The Organizations initial starting point for concern over the failure of analysis in the Proposal starts from the recognition of the over reliance of BLM on State agencies that simply do not align with the mission of the BLM in the creation of the Proposal. This overreliance on the state agencies is even more problematic as there was very little public engagement through State resources on these issues. We are not aware of any CPW public engagement in the development process of their recommendation to the BLM. The Colorado Energy and carbon management commission (“ECMC”) mission is so narrow that no one would think to even monitor ECMC to address issues like route density for recreational usage. After reviewing the public engagement with ECMC, these efforts were clearly addressing energy development and nothing else. This should not be surprise as the ECMC mission statement is clearly stated as:

“To regulate the development and production of oil and gas, deep geothermal resources, the capture and sequestration of carbon, and the underground storage of natural gas in a manner that protects public health, safety, welfare, the environment and wildlife resources.”[5]

The Organizations would be hard pressed to find an agency with less relationship to public lands recreation and multiple use mandates than ECMC. It should be noted that a cursory review of the ECMC proceedings reveals that they have NEVER talked about recreation usage in the last 3 years. This should have been a red flag that the efforts of the ECMC simply would not reflect multiple uses and BLM must address these issues before release of the Proposal.

The Organizations are forced to address the rather troubling direction of efforts from Colorado Parks and Wildlife over the last several years. Historically, CPW was an Agency that worked hard to be the purveyor of high-quality unbiased wildlife information on all issues. While CPW is able to continue this function on certain projects, on many projects CPW is now catering to extreme wildlife organizations and actively seeking to provide information that only supports certain conclusions. Too often CPW documents are created in isolation, without peer review and often shielded from public scrutiny and CPW positions frequently change based on a political whim and fail to provide any basis for these changes. This is disappointing for our Organizations as we have partnered with CPW for decades and have achieved nationally recognized success. This is no longer the voice that is consistently coming from CPW and this type of concern seems to avoid protecting consumptive wildlife and recreational concerns.

Our concerns extend far beyond the expanding consistency with which documents and reports that are foundational to analysis are created with no public scrutiny at all. Recent Commissioner behavior at meetings has been clearly targeted to diminish or reduce public input on issues. The message is clearly sent when the Chair of the Wildlife Commission scolds public input and eventually hangs up on members of the public providing factually accurate input in a meeting on the transparency of CPW activities.[6] This could not be less acceptable despite the fact there is rapidly growing opposition to this type of behavior.[7] The CPW understanding of recreation has diminished greatly in the last several years as exhibited by the fact new commissioners designated to represent recreation on the commission have no background in recreation other than living next to a State Park.

The Organizations again must voice vigorous concern on the Proposal use of CPW recommendations on any issue without further vetting of the recommendations. The input of a state agency allegedly over seeing an issue is not a replacement for the BLM managers requirement that meaningful analysis of these issues is performed and multiple uses are balanced in accordance with federal statutory requirements.

The Organizations are also aware that there is litigation allegedly driving part of this planning effort. At no point are we able to locate any portion of this settlement that absolves BLM of their statutory obligation to address multiple uses in planning.

Courts have consistently found that while State agencies and other partners may participate and draft NEPA documents the ultimate responsibility for compliance with the NEPA requirements and multiple use mandates remains with the federal agency. [8] Recent reforms and clarifications of the absolute responsibility of BLM managers to comply with NEPA requirements was recently added in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. The Organizations must take a hard look at this Proposal and the high levels of engagement asserted to be achieved before this was brought to the BLM

”(D) ensure the professional integrity, including scientific integrity, of the discussion and analysis in an environmental document;

(E) make use of reliable data and resources in carrying out this Act;”[9]

The Organizations vigorously assert this requirement simply has not been achieved with the Proposal as it was created by an Organization that has no statutory authority over multiple uses, or is even a primary manager of wildlife, mainly ECEC. This was then shared with CPW that as far as we are aware did nothing more than rubber stamp the Proposal as no public comment was undertaken. While we do not contest that partners can have an active role in the development of NEPA, NEPA can be done with partners but does not absolve the agency mandate to confirm compliance with legal requirements.

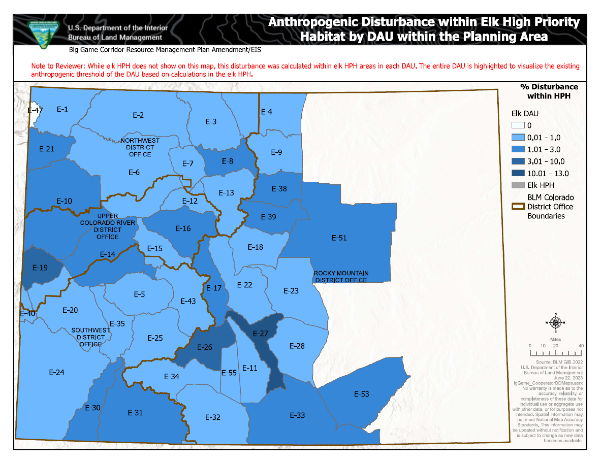

The Organizations are supporting Alternative A of the Proposal as every other alternative in the Proposal starts from a foundational flaw. Mainly the analysis claims to address route density in only certain designations such as High Priority Habitat (“HPH”) or winter range but then seeks to apply these conclusions to the entire GMU. This forces us to ask the question of why would any effort be directed towards the designation of winter range and other existing habitats if management decisions are simply applied to the entire planning area. No explanation of how this decision was made or factors that it was seeking to address were ever provided, despite this being an entirely unprecedented application of these analysis. The Organizations are aware that extensive portions of HPH are not even found worthy of designation as an ACEC after site specific review in the planning process.

Not only is this decision entirely unprecedented and unsupported it also fails to recognize there are massive tracts of lands that will never be available for oil and gas exploration, such as Congressionally designated Wilderness, National Monuments and Parks. This issue is simply not addressed at all in the allocation of HPH analysis to the larger landscape. This is a complete violation of multiple use mandates for the management of public lands. While wildlife is an important component of recreation and the Colorado way of life, it is also merely a multiple use on public lands. The only species that are outside the multiple use mandate are those that are protected by the Federal or State Endangered Species Acts, and even in these situations there are significant protections for multiple uses. The Organizations are very concerned that the Proposal would simply avoid all these requirements for the use and management of public lands and place wildlife above all other concerns.

The Organizations are very concerned that the Proposal continues to lack basic definitions that are a foundational to the implementation of the Proposal in the future and the basic accuracy of information that is being presented currently. Without basic definitions any assertion that sufficient NEPA has been prepared is factually problematic or that analysis has been consistently prepared from unit to unit. The example of the failure of the Proposal to define terms is evidenced by the lack of definition for the concept of an “oil and gas route” despite this concept being heavily restricted in the Proposal. Understanding the concept of an “oil and gas route” in foundational to our concerns about unintended consequences of the Proposal.

The immense amount of conflict between discussions of similar issues present in the Proposal and related analysis is immense. The Organizations are simply unable to understand what the decision or proposal is that is being presented in order to make an intelligent comment. The conflicting analysis and basic positions in the Proposal starts almost immediately as the Proposal starts from the position:

“The purpose of this RMPA process is to evaluate alternative approaches for oil and gas planning decisions to maintain, conserve, and protect big game corridors and other big game HPH on BLM-administered lands and Federal mineral estate in Colorado. This draft RMPA/EIS establishes goals, objectives, and needs to address conflicts or issues related to oil and gas development and big game HPH.”[10]

The Proposal continues this discussion as follows:

“During the scoping and alternatives development process, a number of individuals and cooperating agencies requested that the BLM consider an alternative that would address other non-oil and gas land uses, such as recreational trail development, renewable energy (e.g. solar farms), and livestock grazing. This recommendation was based on the supposition that there is a correlation between other non-oil and gas land uses and declines in big game populations or significant degradation of high priority habitat on BLM-administered public lands within the decision area. This alternative was considered but eliminated from detailed analysis because under each of the alternatives considered in detail”[11]

The immediate and complete conflict of these positions on recreation and trails starts almost immediately in the Proposal as goal #4 of the effort is summarized as follows:

“OBJECTIVE: During each 5-year period following RMPA approval, identify, reclaim, or enhance acres of HPH for big game habitat statewide. Priority treatment areas should include (but are not limited to) aspen, riparian areas, winter range, and migration/connectivity areas. Actions to help accomplish this objective in relations to and as mitigation for oil and gas developments may include:

The Organizations are entirely unable to align any assertion the Proposal does not address recreational access and routes when the clearly stated Goal #4 of the Proposal is to address recreational access. Any assertion that Goal #4 is incorrectly stated is simply without factual basis as the Proposal provides extensive analysis of the relationship of recreational trails and the goals and objectives of the Proposal as follows:

“Continued and increased use of roads and trails, both by motorized and nonmotorized users with increased populations in Colorado and interest in using public lands for recreation could lead to increased recreation pressure, which would continue to disturb vegetation that could result in a reduction of soil stability and a corresponding increase in erosion rates. Road construction has also occurred in association with timber harvesting, historic vegetation treatments, energy development, and mining on BLM-administered lands, private lands, State of Colorado lands, and National Forest System lands. The bulk of new road building is occurring for community expansion and energy development. Road construction is expected to continue and could also contribute to reductions in vegetation cover under all alternatives, particularly when combined with fluid mineral development.”[13]

We are simply unable to align this provision in any meaningful manner with the assertion that trails and recreation are not within the scope of the analysis. The conflict between basic positions on recreation only expands when subsequent portions of the Proposal are reviewed:

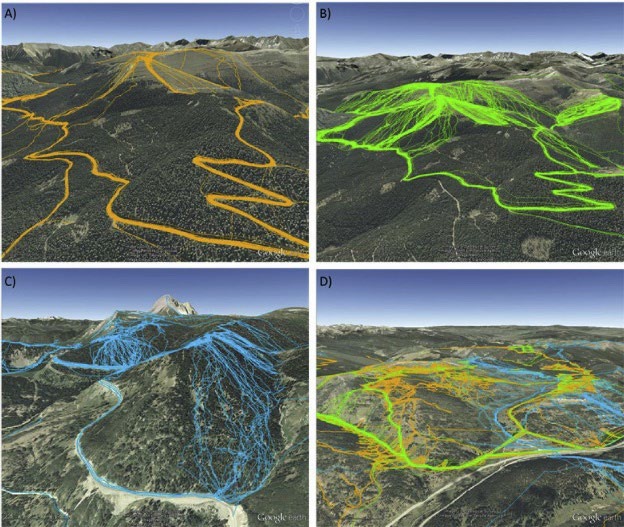

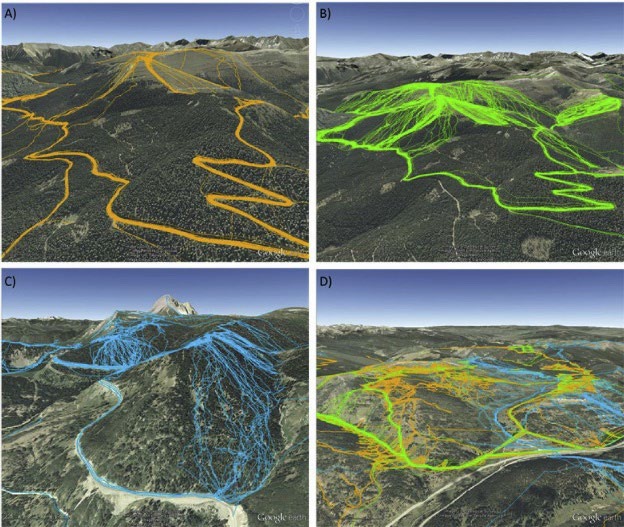

“For density outputs related to trails, the Colorado Trail Explorer (COTREX) was used as a data source for every trail in the state of Colorado. COTREX connects people, trails, and technology by coordinating the efforts of federal, state, county, and local agencies to create a comprehensive and authoritative repository of recreational trails for public use. COTREX represents a seamless network of trails managed by over 225 land managers.”[14]

Rather than recreational access being removed from further analysis in the Proposal as asserted, the Proposal specifically includes recreational access as a factor to be addressed in calculation. Rather than addressing possible impacts to recreation from the Proposal, the Proposal introduces the new concept of compensatory mitigation where trails could be closed to offset oil and gas development. The Proposal outlines this model for compensatory mitigation of oil and gas impacts as follows:

“The BLM may require compensatory mitigation to offset disturbance or density limitation exceedances and the functional loss of habitat from oil and gas development in HPH. The BLM will ensure that compensatory mitigation is strategically implemented. The compensatory mitigation program will be implemented at a state level in collaboration with BLM’s partners (e.g., federal, tribal, and state agencies). Compensatory mitigation may include reclamation of existing disturbances outside of the proposed development (e.g., orphaned oil and gas development, redundant travel routes, unauthorized route and recreation use, fence removal), establishment, enhancement, and preservation of big game HPH (e.g., seeding, noxious weed control, vegetation treatment). Compensatory mitigation requirements may match the magnitude of the anticipated impacts.”[15]

The Organizations are even more concerned that the exceptionally small amount of information that is provided on compensatory mitigation creates more confusion and conflict than it resolves. The desire to create compensatory mitigation program is clearly identified as follows in the Proposal:

“OBJECTIVE: Implement an effective compensatory mitigation program consistent with state regulation and policy that compensates for adverse direct and indirect impacts to big game HPH at multiple scales, including the landscape scale, caused by the authorization of oil and gas development activities where cumulative disturbances from land uses on BLM-managed lands and minerals may impede migration or otherwise impair the function of big game HPH. The compensatory mitigation program should provide ample financial resources to offset functional habitat loss and result in conservation benefit to the species, consistent with BLM’s Manual Section (MS-1794) and Handbook (H-1794-1).”[16]

The Organizations would be vigorously opposed to the creation of an entirely new program for compensatory mitigation as this is entirely outside the scope of the Proposal. When we are presented with goals and objectives of the Program that are outlined as “ample financial resources” we must ask who manages these funds, who determines what an ample financial resource is and how it would be allocated.

The Proposal entirely fails to describe what compensatory mitigation means, who would administer the compensatory mitigation program outside its abstract financial goals and objectives, how it would be calculated or applied is never discussed in the Proposal. The Organizations concerns around this concept only expands when concepts such as “functional loss of habitat” or indirect impacts are addressed, as these concepts simply are not even defined. We must ask what an unauthorized recreational usage even is as most recreational usages, outside motorized activities, are entirely unmanaged on public lands.

The immediate concern would be administration as given the cavalier method of addressing state involvement, this compensatory mitigation effort could be allocated to ECMC, which is an organization that has ZERO background or experience with recreational opportunities. After a brief review of the ECMC statutory authority, which we recognize can require performance and surety bond obligations for drilling and other activities, we are unable to identify any authority of ECMC to collect or manage funds in the manner or any checks and balance s on the allocation of these funds that they will be used in the manner proposed. [17]

Rather than avoiding conflict with routes that are allegedly grandfathered, the Proposal creates immediate conflict between these uses, as there will be an incentive for oil and gas exploration efforts to close existing trails. The Organizations vigorously oppose any assertion that the Proposal avoids impacts to recreational access as this is one of the primary goals of the Proposal and one of the primary tools to be utilized in the implementation of Proposal.

As the Organizations have previously noted the Proposal fails to provide even basic guidance on general concepts or ensure that the concept is within the scope, purpose and need of the EIS. While many of these concepts are highly complex and outside the scope of comments from a recreationally based interest, the Organizations concerns explode when these concepts proposed are attempted to be applied to travel management concepts and larger efforts around recreational access on public lands. The Organizations are aware that many basic concepts in recreation that are well settled, such as Wilderness or Roadless Areas are not even mentioned in the Proposal.

When application of the Proposal to the more nuanced but highly critical analysis of travel management is attempted, the Proposal simply fails in almost every way possible. The need to define the concept of an “oil and gas route” in the Proposal is critical as routes can take many forms, and while the BLM may only designate routes, as the Proposal seeking to address USFS and BLM lands, we must also recognize that the USFS designates many types of routes including:

The Proposals fail to address these specific designations is exemplified by the consistent referral to all access methods as routes without recognizing there are dozens of types of routes. If a compensatory mitigation program is being created with the Proposal that would be applied on USFS managed lands, alignment with USFS regulations on roads and trails would be critical to its implementation. Understanding such as this is critical to understanding possible impacts to wildlife and development of a functional compensatory mitigation program. Most of these routes are unrelated to oil and gas and have widely variable impacts to wildlife.

The immense number of types of routes must be addressed in the Proposal as we have trouble seeing a 30inch wide dirt path being identified as an oil and gas route. The need for basic definitions only becomes more critical as the nature of the usage of the route must also be addressed to determine an oil and gas route. The Proposal completely fails to provide guidance on what an oil and gas vehicle would be, making identification of an oil and gas route functionally impossible.

The vast majority of vehicles on Colorado roadways are entirely unrelated to oil and gas activities but the Proposal provides such a comically broad definition of vehicle as to render the definition of vehicle useless for identifying an oil and gas route. Motorized vehicle as defined in the Proposal directly conflicts with Colorado statutes on a profound and basic level as the Proposal provides the following definition.

“Motorized Vehicles—Vehicles propelled by motors or engines, such as cars, trucks, off-highway vehicles, motorcycles, snowmobiles, and boats.”[18]

The Organizations simply cannot overlook the utterly astonishing that the Proposal feels the need to identify boats as a motor vehicle within the scope of analysis of the Proposal. We must question how this category of usage was thought to be necessary. While exploration for oil and gas with boats may be common in the Gulf of Mexico, we are unable to identify any oil and gas drilling that has occurred in Colorado that relies on boats.

Given that the Proposal appears to be creating a compensatory mitigation program that would then be administered by ECMC, basic alignment of the scope of the compensatory mitigation program and existing Colorado law would be a foundational concern. The Proposal completely fails at this type of alignment. There is no mention that OHVs are not motor vehicles under CRS, but rather are separately defined as “Off-highway Vehicles” under Title 33-14.5 of the CRS. The overwhelming portion of roads are not available for OHV use in Colorado. Snowmobiles are also clearly not motor vehicles within general provisions of CRS but are separately identified as “over the snow vehicles” under CRS 33-14. By operation of Forest Service regulations snowmobiles do not operate on roads, regardless of the width of the route. These routes are identified as trails simply to identify the lower level of maintenance on groomed trails and the fact these routes are not available for wheeled vehicles. These definitions are in comical conflict with assertions that the Proposal will not impact travel management decisions. The Proposal clearly does not even understand the basic concepts of travel management.

While the Proposal includes boats in the scope of analysis, the Proposal fails to recognize that huge portions of oil field work in performed by heavy equipment, such as road graders, bulldozers, front end loaders, back hoes, excavators, heavy specialized pumping equipment heavy duty truck-based drilling equipment and commercial heavy duty transport trucks. Absolutely none of this type of usage is addressed in the Proposal, despite the fact often these are not motor vehicles under Colorado statutes. Colorado statutes provide numerous other designations for these types of vehicles all of which specifically remove them from the definition of a motor vehicle. As examples of this would be CRS 35-38-102 which specifically defines equipment as follows:

(2) (a) “Equipment” means a machine designed for or adapted and used for agriculture, horticulture, floriculture, livestock, grazing, light industrial, utility, and outdoor power equipment. “Equipment” does not include earthmoving and heavy construction equipment, mining equipment, or forestry equipment.

The need for a basic definition of the equipment within the scope of a motor vehicle is immediately apparent as Colorado uses many different provisions to define equipment and they are all different. CRS 42-1- 102(33) which provides a definition of farm tractor as follows:

(33) “Farm tractor” means every implement of husbandry designed and used primarily as a farm implement for drawing plows and mowing machines and other implements of husbandry

CRS 42-1-102 again provides a specific definition of implement of husbandry

“(44) (a) On and after July 1, 2000, “implement of husbandry” means every vehicle that is designed, adapted, or used for agricultural purposes. It also includes equipment used solely for the application of liquid, gaseous, and dry fertilizers. Transportation of fertilizer, in or on the equipment used for its application, shall be deemed a part of application if it is incidental to such application. It also includes hay balers, hay stacking equipment, combines, tillage and harvesting equipment, agricultural commodity handling equipment, and other heavy movable farm equipment primarily used on farms or in a livestock production facility and not on the highways. Trailers specially designed to move such equipment on highways shall, for the purposes of part 5 of article 4 of this title, be considered as component parts of such implements of husbandry.”

As another example of why a specific definition of oil field is needed is the fact CRS 41-2-102 provides a specific definition for special mobile machinery:

“(93.5) (a) “Special mobile machinery” means machinery that is pulled, hauled, or driven over a highway and is either:

(I) A vehicle or equipment that is not designed primarily for the transportation of persons or cargo over the public highways; or

(II) A motor vehicle that may have been originally designed for the transportation of persons or cargo over the public highways, and has been redesigned or modified by the addition of mounted equipment or machinery, and is only incidentally operated or moved over the public highways.

(b) “Special mobile machinery” includes vehicles commonly used in the construction, maintenance, and repair of roadways, the drilling of wells, and the digging of ditches.”

The compelling need for a basic definition of what is and is not included within the scope of the Proposal could not be more directly evidenced by this situation. While the Proposal has managed to address the use of boats within the definition of motor vehicles for oil field operations, we simply cannot see boat management as a concern in the operation of oil and gas operations in Colorado. That is simply silly. How boats were thought to be worthy of inclusion of the definition, equipment is simply not even mentioned in the definitions.

This is despite the myriad of definitions and classifications that are available for equipment under Colorado statutes this is not addressed but OHVs are defined in multiple locations in the Proposal. While the Proposal asserts to not be impacting existing travel management, based on the information and definitions provided, the motorized recreational community is left with the feeling that we are the target of this Proposal. Again, the immediate conflict between the intent of the Proposal and implementation of the Proposal could not be more stark. If protection of wildlife is the priority, wouldn’t a proposal that addressed 100k lbs. trucks traveling on high-speed roads be a higher priority than an off-highway motorcycle, ATV or SxS or boat? Contact between trucks and wildlife are commonplace and contact with an OHV is almost entirely unheard of. Contacts between deer and elk and a boat are simply foolish to even address in a Proposal, but yet the Proposal seems to think this is enough of an issue to include boats as a motor vehicle.

As we have previously noted the Proposal completely fails to provide a definition of a motorized vehicle that encompasses normal oil field activity or a definition of route that is of any value whatsoever is problematic. The confluence of these two failures results in profound problems for the Proposal when it is implemented. How is anyone supposed to understand how to identify what an oil and gas route even is? This would be the first step to implement the Proposal. This is a basic problem that immediately causes concern around the adequacy of NEPA analysis. How is route density calculated? Does this only include routes that are under the exclusive control of the oil field permitees to connect the well site to a public roadway? Even with exclusive usage, questions such as how often the route is used and for what is the route being used are a problem. We doubt that is the issue.

These challenges are immediately concerning if the route connecting the pad site is not open to the public but is used for many permitted uses such as a rancher using a route to access infrastructure or private land owners using the route in addition to the oil and gas permittee? How can these uses be divided without definitions? The answer is they cannot and this will immediately create unintended impacts from the Proposal.

If the definition of oil and gas route is broader than the short connector between a public roadway and a well pad that is exclusively used by the permittee, we are immediately faced with problems on the lack of a definition for oil and gas equipment or motorized vehicle. If we had clear definitions for these uses at least we could have a meaningful discussion exploring levels of usages of these mixed usage public routes. These discussions could include levels of oil and gas traffic compared to other uses of the roadway. But we cannot even do that as the Proposal includes everything from horses to canoes to mountain bikes as routes that should be taken into account. This makes us think something is very wrong with the direction of the Proposal, and as a result we are supporting Alternative A simply to avoid the massive unintended impacts of the Proposal.

Clearly a low speed two track trail with seasonal closures is of far less threat than a high speed arterial road, such as I-70. In many of the areas addressed by the Proposal usage of the high speed arterial roads are so complete as it fully displaces wildlife. This stands in direct conflict to a seasonally closed single track trail that is well managed and only used sporadically. These types of routes are frequently identified as benefit to wildlife and forest health.

While the Proposal fails to define uses critical to its asserted purpose, many definitions are provided that are entirely outside the scope of an oil and gas type concern. This causes us immense concern that the intent of this Proposal was never the desire to mitigate just oil and gas activities in possible wildlife corridors, but rather to mitigate all usages. As the Organizations have noted above there are serious concerns with the Proposal failure ot provide basic definitions to address uses that might be commonly found with oil and gas exploration. Two examples of definitions are provided but are entirely outside the scope of any oil and gas activity we have encountered would be:

“Non-mechanized Travel—Moving by means without motorized or mechanized equipment, such as hiking and horseback riding.”[19]

“Mechanized Travel—Moving by means of mechanical devices not powered by a motor, such as a bicycle.”[20]

We are very concerned that while the use of mountain bikes or horses simply does not occur with enough frequency to warrant discussion if the intent of the Proposal is to only address oil and gas usage, that the inclusion of these types of definitions provides insight into the scope of the effort, which is entirely unrelated to oil and gas activities. If the intent of the Proposal is to develop a cap-and-trade type program where competing interests must purchase the ability to do anything on public lands, this scope of review would be appropriate. Again, this is VERY concerning for the Organizations and would be opposed by us until FAR more clarity on the process has been provided.

The Organizations are vigorously opposed to the fact that that the mere application for an oil and gas permit is now something we are going to have to monitor. The process outlined in the Proposal indicates that compensatory mitigation would occur before the permitting process was approved and before anything occurred on the ground. We are also very concerned mere presence of a permit to use the road or trail does not make the route more of a risk to wildlife. Again, these are concepts and concerns that might be abstract if the Proposal was limited to addressing oil and gas impacts creating possible wildlife issues in corridors. We do not believe this is the intent or direction for the Proposal as we believe the intent is to create a cap-and-trade program for all actions on public lands in Colorado, which we oppose as the recreational community simply is not in a position to begin to allocate resources in this manner.

The failure of the Proposal to undertake basic analysis in a meaningful manner has led to issues that are unresolvable in the implementation of this Proposal. Mainly what are these wildlife corridors called moving forward. Multiple uses must be balanced based on existing designations. Are they Areas of Critical Environmental Concern? Are they a general management category? Statutorily provided authority for Areas of critical environmental concern exists, which is defined as follows:

“(a)The term “areas of critical environmental concern” means areas within the public lands where special management attention is required (when such areas are developed or used or where no development is required) to protect and prevent irreparable damage to important historic, cultural, or scenic values, fish and wildlife resources or other natural systems or processes, or to protect life and safety from natural hazards.”[21]

While the Proposal appears to be elevating wildlife above other uses in a manner similar to the designation of an ACEC, the analysis falls well short of sufficient information to support the designation of ACEC. ACEC designations require public engagement on a site specific analysis of the characteristics that are important and relevant to the designation of the ACEC. The failure of the Proposal to even begin to address important and relevant characteristics of these areas would preclude any discussions of how these new analysis areas would be integrated into BLM management requirements is again an example of the complete failure of the Proposal to address issues with any level of legal sufficiency.

A brief review of NEPA requirements provided in regulation, various implementation guides and relevant court rulings is warranted to allow for comparison of analysis provided in the Proposal and the proper standards for this analysis. The Organizations believe that the high levels of quality analysis that is required by these planning requirements frequently gets lost in the planning process. The Organizations are very concerned that the need to document the cause-and-effect relationship between management changes and impacts that will result is a significant weakness in the Proposal. It is well established that NEPA regulations require an EIS to provide all information under the following standards:

“… It shall provide full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts and shall inform decision makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives which would avoid or minimize adverse impacts or enhance the quality of the human environment….. Statements shall be concise, clear, and to the point, and shall be supported by evidence that the agency has made the necessary environmental analyses…. “[22]

The regulations included the development of the Council of Environmental Quality, which expands upon the detailed statement theory for planning purposes.

“You must describe the proposed action and alternatives considered, if any (40 CFR 1508.9(b)) (see sections 6.5, Proposed Action and 6.6, Alternative Development). Illustrations and maps can be used to help describe the proposed action and alternatives.”[23]

These regulations clearly state the need for the quality information being provided as part of this relationship as follows:

“The CEQ regulations require NEPA documents to be “concise, clear, and to the point” (40 CFR 1500.2(b), 1502.4). Analyses must “focus on significant environmental issues and alternatives” and be useful to the decision-maker and the public (40 CFR 1500.1). Discussions of impacts are to be proportionate to their significance (40 CFR 1502.2(b)).” [24]

The Organizations are intimately aware of the high burdens placed on all phases of any project under the National Environmental Policy Act, as the Organizations have undertaken many NEPA analysis in partnership with Federal Agencies in Colorado. The Organizations do not believe a comparable level of analysis and resources have been directed towards the Proposal preparation, despite the much larger issues and concerns that are addressed in the Proposal, and the failure to perform these analysis has directly resulted in a Proposal that suffers from numerous critical flaws. The Organizations believe this full and fair discussion of many issues has not been provided in the Proposal.

The Organizations believe the association of impacts from changes proposed to the management issue that is the basis is a critical component in developing public comments and involvement as frequently members of the public do not have sufficient time, resources or understanding to make these connections. These concerns are summarized in the NEPA regulations which clearly provide the reason for the need for high quality information to be provided in the NEPA process. NEPA regulations provide as follows:

“(b) NEPA procedures must insure that environmental information is available to public officials and citizens before decisions are made and before actions are taken. The information must be of high quality. Accurate scientific analysis, expert agency comments, and public scrutiny are essential to implementing NEPA. “[25]

The desire for NEPA analysis to stimulate public involvement and comment as part of federal planning actions is woven throughout the NEPA regulations and the implementation documents that have been created by BLM for NEPA issues. The BLM Planning manual clearly states:

“The CEQ regulations also require that agencies “make diligent efforts to involve the public in preparing and implementing their NEPA procedures” (40 CFR 1506.6(a)).”[26]

The Organizations vigorously assert that high quality information on numerous issues has simply never been provided in the Proposal, as the Organizations are forced to theoretically address numerous issues despite the asserted priority and importance of the issues in the Proposal. The lack of high-quality information has materially impaired the Organizations ability to meaningfully and completely comment on a variety of issues.

Given the numerous documents and guidelines that have been overlooked in the creation of the RMP, the Organizations believe that that this failure has caused the range of options to be directed in a manner that is improper compared to the direction the range of alternatives would have addressed had these guidelines and documents been accurately addressed when the original vision for the RMP was created. Given the foundational nature of these documents, the travel management portion of the plan should be withdrawn to allow for complete and accurate inclusion of these foundational documents in the creation of the RMP.

After a review of the DRMP, the Organizations vigorously assert there has not been sufficient analysis of numerous issues to satisfy general NEPA planning requirements. The NEPA regulations clearly state the general standards for analysis of issues in an EIS as follows:

“Agencies shall focus on significant environmental issues and alternatives and shall reduce paperwork and the accumulation of extraneous background data. Statements shall be concise, clear, and to the point, and shall be supported by evidence that the agency has made the necessary environmental analyses. An environmental impact statement is more than a disclosure document. It shall be used by Federal officials in conjunction with other relevant material to plan actions and make decisions.”[27]

The Proposal encompass over hundreds of pages but fails to provide any meaningful discussion of economic and travel management issues, both of which have received significant public input.

As previously noted, NEPA requires a detailed statement of why a decision or alternative was chosen over other alternatives. The detailed statement is required on a wide range of topics, some of which often conflict. One of NEPA’s fundamental goals is to:

“promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of man.” [28]

As more completely addressed later in these comments, the Organizations have serious concerns that the welfare of man, more specifically the economic welfare of man, has not been properly addressed in the planning process. The Organizations believe the Proposal falls well short of stimulating the welfare of the residents that live in the local communities.

NEPA further requires that cumulative impacts be taken into account as follows:

“Cumulative impacts can result from individually minor but collectively significant actions.”[29]

The Organizations believe these cumulative impacts can take many forms, including not only addressing cumulative impacts to the environment but also addressing the cumulative impacts of the decisions made on a site-specific basis as part of the landscape level planning process. The Organizations also believe cumulative impacts of exclusions in the analysis of specific factors must also be properly addressed. The Organizations believe this has not occurred when addressing the stimulation of the welfare of man.

The Organizations believe a brief summary of the standards that are applied by Courts reviewing agency NEPA analysis is relevant to this discussion as the Courts have consistently directly applied the NEPA regulations to EIS review. Relevant Court rulings have concluded as follows:

“an EIS serves two functions. First, it ensures that agencies take a hard look at the environmental effects of proposed projects. Second, it ensures that relevant information regarding proposed projects is available to members of the public so that they may play a role in the decision making process. Robertson, 490 U.S. at 349, 109 S.Ct. at 1845. For an EIS to serve these functions, it is essential that the EIS not be based on misleading economic assumptions.”[30]

As previously addressed in these comments, public involvement simply has not been stimulated and a hard look has not been performed. The high levels of frustration expressed from the public in response to the release of the Proposal speaks volumes to the quality of information provided and the ability of the public to comment on the information.

The Organizations expressed significant concerns with the factual and scientific basis of the proposed mile per mile route density standard in our scoping comments. It is woefully inadequate as every alternative in the EIS caps density at a 1 mile of route per square mile standard. Unfortunately, rather than addressing the concerns raised in the scoping about the viability of this standard, the EIS avoids this question all together. Again, we must ask how this standard was developed and what are the benefits of the 1 route mile per square mile standard when compared to a standard of 2 route miles per square mile or 3 route miles per square mile. As we noted in scoping, we are aware of numerous proposals that supported route densities of 4 to 5 miles of routes per square mile in designated critical habitat for endangered species. Given that deer and elk are only protected as a multiple use of public lands, rather than as an Endangered Species, the mile per mile standards simply does not reflect existing planning, special designations of lands by Congress or other factors.