May 8, 2015

Director(210)

Att: Protest Coordinator

20M Street SE, Room 2134LM Washington, DC 20003

Re: Appeal of Grand Junction FRMP

Dear Sirs,

Please accept this correspondence and attachments as the appeal and objections of the above Organizations with regard to the BLM Grand Junction Final Environmental Impact Statement (“FEIS”) and Resource Management Plan (“RMP”). For purposes of this appeal/protest these documents will be collectively referred to as “the Proposal” . It is the Organizations position that the analysis of cultural resource management is insufficient, is arbitrary and capricious as a matter of law and fails to provide the hard look at issues mandated by NEPA. Additionally the proposed management of cultural resources fails to properly balance multiple use management standards with the protection of cultural resources, as the RMP seeks to manage possible cultural sites as a trustee would manage a trust rather than as a balanced multiple use of public lands.

Prior to addressing the appeal/protest of the Proposal, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization the 150,000 registered OHV users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to insure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA advocates for the 30,000 registered snowmobiles in the State of Colorado. CSA has become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling by working with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators. For purposes of this document, CSA, COHVCO and TPA are identified as “the Organizations”.

The Organizations comments on the draft RMP are submitted with this appeal/protest as an attachment.

1. Executive Summary.

The Grand Junction RMP proposes to close 1,894 possible cultural sites, 612 miles of existing routes and 53,500 acres to all surface disturbing activity for protection of possible cultural resources sites. This is expansion in management by a factor of 236 from the 8 sites currently managed and an expansion of 5x the number of acres to be closed. Route closures due to cultural resource concerns are second only to Endangered Species issues, which are closing 672 miles of routes. The relationship of ESA issues are significant as ESA is the only factor that is addressed outside the multiple use management process.

The Organizations submit that the sheer scale and impact of these management changes simply has not been analyzed in a manner that could be sufficient to satisfy NEPA. This level of expanded management directly conflicts with current management of sites, which only identifies 3 of the 1,894 sites as being on the National Register and manages 8 sites currently. By comparison there are only 50 sites in Mesa and Garfield Counties on the National Register, 1,492 sites in the entire state of Colorado and that the District of Columbia only has 597 sites. The Organizations submit that these levels of expansion of any management issue would warrant a rather detailed discussion of the necessity of such management and especially how the expansion was justified under multiple use mandates. This simply has not been provided.

Additionally, of the 1,894 sites identified only 7 were released from further management meaning that 99.3% of the sites identified were found suitable for management. The Organizations believe such a high acceptance rate for any activity in multiple use planning is an indication that the required balance of multiple use was badly out of balance. The reasoning for

exclusion of these sites from further management also indicates an imbalance of multiple usage as the sites excluded from management were either sold by the BLM or destroyed by fire making further management impossible. The Organizations submit there is a significant difference between a site being “impossible to manage” and being “suitable to manage” and this distinction is simply never raised in the FRMP.

The Organizations are concerned about the imbalance of usage resulting from cultural resource management standards as these impacts are not remote or abstract and run well beyond the mileage of routes proposed to be closed. Each of the 1,894 sites identified in the GJFO RMP is subjected to a mandatory closure to surface disturbing activities of at least 100 meters and possibly 200 meters around the site to all surface disturbing activities including trails and recreational usage, oil and gas, grazing and many other uses. While defining surface disturbing activity would be a critical step in balancing usages, the RMP simply fails to define this term. This begs the question of how was the required hard look at balancing usages in any area undertaken when the usages to be prohibited is simply never defined. The Organizations further submit that implementation of this standard will directly conflict with a wide range of federal laws and other agency planning efforts.

The Organizations submit that a proper balancing of multiple usages with cultural resource protection is impossible with the current inventory and management. The exceptionally limited information in the cultural site inventory provided in appendix I clearly finds that 27% of the sites identified either need data or further assessment. The Organizations submit this void of data is direct evidence that cultural resource were arbitrarily given a priority position in balancing multiple uses, as the Organizations are unsure how this balance could be made when land managers are not aware of what is at the site or the true size of the site. The Grand Junction RMP simply fails to address the basis for management of 27% of the cultural sites to be closed and how the balancing of multiple uses has occurred in the decision making process. The Organizations are aware that while the specific locations of cultural resources sites are confidential, this confidentiality of sites is not a waiver of NEPA analysis.

The Organizations submit that the limited information inventory of cultural sites further provides that 51% of the 1,894 sites identified are “not eligible” for protection on the National Register. Again the Organizations must question how multiple uses are balanced with these sites as there is no distinction in the management standards being applied between sites that might be eligible and those areas that are not eligible for listing. It is the Organizations position that eligibility has to play a large factor in balancing multiple uses and the management closures that are related to each site. The Organizations are also concerned that the lack of data and ineligibility of a site does not appear to have impacted the allocation of sites to a particular usage category. These classifications are simply scattered throughout the usage categories.

The Organizations submit that if the required balancing of multiple uses had occurred, the fact that 78% of the sites proposed to be mandatorily closed were either lacking data or wholly ineligible for listing on the national register would have weighed against mandatory closures for these sites. The Organizations further submit that the fact the 7 sites discharged from further management were either destroyed or sold directly evidences the failure to balance multiple uses. The Organizations submit that the fact that any usage obtaining 99.3% of their issue in a multiple use management situation is an indication that the factor or issue was not balanced but rather was to be managed as trustee would manage a trust.

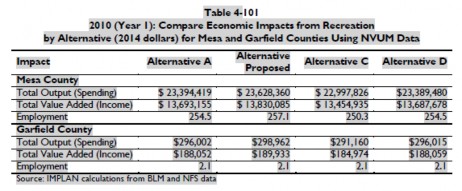

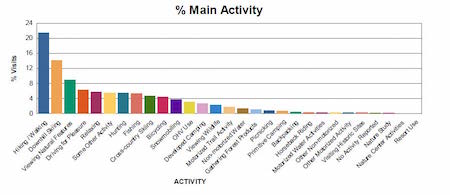

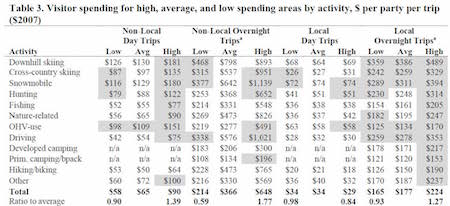

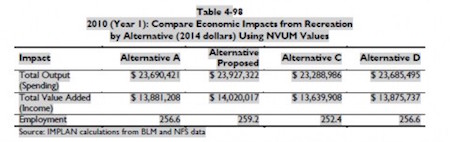

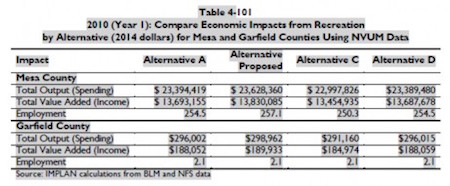

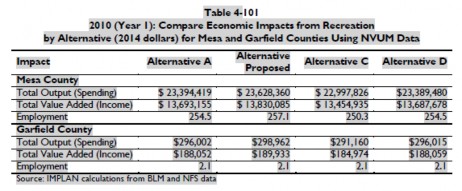

Even more serious concerns about the proper balancing of multiple usages in cultural sites result from changes in between the draft and final RMP, where recreational economic contributions in value and related jobs were expanded to almost 7 times original estimates. Many routes were reopened due to the heightened importance of recreation. While the economic contribution of recreational activity was expanded to 7 times original estimates, there was simply no change in any aspect of cultural resource management despite the fact that closures of 1,894 sites at least a football field in size to all usages could clearly have an impact on recreational access and the economic benefits that flow to local communities as a result. Again cultural management analysis remains completely unchanged between the draft and final RMP.

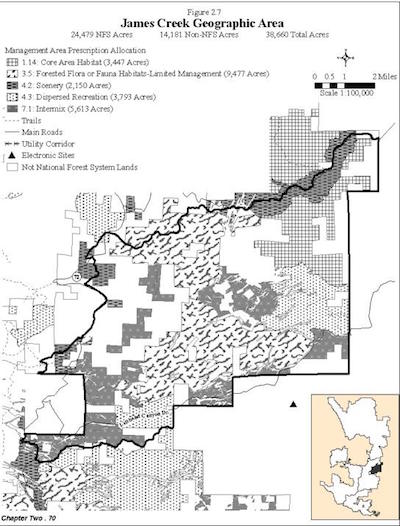

The Organizations submit that management of cultural sites as a trustee has also precluded viable management options for these areas such as moving to a designated trail system, which would provide a far more balanced usage of resources and protection of sites. The mandatory closing these sites would clearly impact routes that are critical to accessing other recreational opportunities that are totally unrelated to the cultural sites. The Organizations believe an economic analysis of the impacts to recreational access from these mandatory requirements would be highly site specific, as there are numerous geographic limitations in the GJFO which would severely impact access to significant portions of the field office. In numerous areas trails and routes are at the bottom of canyons and large washes due to steep and rugged terrain. The Organizations are forced to believe that many of the same geographic limitations currently in the field office forced herd animals and the Indians through the same canyon bottoms hundreds of years ago as are now being used for recreation. Expansion of recreational spending and jobs would clearly weigh against current closures in an area such as these types of bottlenecks as recreational values for the areas lost outside the bottleneck areas would be exponently higher.

The Organizations submit that the impacts of the failure to properly balance cultural resource management in the NEPA process is neither speculative or remote. Typically Endangered Species habitat issues are a primary basis for route closure as the ESA places the listed species at a higher priority than multiple use issues. Only 672 miles of routes were closed in the GJFO final RMP due to all endangered species issues. Our basis for concern on balancing of usage is 616 miles of routes were lost exclusively due to cultural resource management concerns again indicating there is an imbalance in this issue. The Organizations are further concerned regarding the long term impacts of these management standards as any site specific work in the future would be subjected to mandatory closures and probably result in additional lost routes and an impossibility to build new routes.

The Organizations vigorously assert that management standards for lynx habitat areas adopted by the GJFO directly conflict with the 2103 Conservation Assessment and Strategy and as a result are arbitrary and capricious. The 2013 LCAS specifically states that a multi-story actively managed forest is critical to the lynx survival and that snowmobile usage and snow compaction is a significantly decreased threat to the lynx and that currently levels of management are acceptable. The FRMP proposes to close the lynx analysis areas to all timber harvest and close these areas to snowmobile usage despite the fact these areas have been open to snowmobile usage for decades.

2a. Standard of review for NEPA decisions on appeal.The Organizations believe a brief summary of the standard of review applied by Courts reviewing agency NEPA analysis is relevant to this discussion, as the Courts have consistently directly applied the NEPA regulations to EIS review. As a general review standard, Courts have applied an arbitrary and capricious standard of review for agency actions under NEPA. This standard is reflected as follows:

“…it required only that the agency take a “hard look” at the environmental consequences before taking a major action. See, Kleppe v. Sierra Club, 427 U. S. 390,427 U. S. 410, n. 21 (1976). The role of the courts is simply to ensure that the agency has adequately considered and disclosed the environmental impact of its actions, and that its decision is not arbitrary or capricious. See generally, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401 U. S. 402, 401 U. S. 415-417 (1971).”1

The Organizations vigorously assert that a hard look has not been taken on cultural resource issues and endangered species management issues. The Organizations submit that the expanded scale and scope of protection of cultural resources is simply unprecedented as 99.3% of the sites proposed are found to be worthy of management and is arbitrary and capricious as a matter of law and a direct violation of cultural resource laws. The failure to properly balance cultural resource management with other multiple uses is also a violation of law as management is clearly reflected a trustee type position being taken for cultural resources to the detriment of other multiple uses to be balanced in a NEPA analysis.

The arbitrary and capricious nature of the cultural resource management standards is further evidenced by the fact that usages that created some of the sites is now prohibited from continuing as exemplified by the fact that routes created for or by multiple use are now closed to multiple use in order to protect the cultural values of the route. This position completely lacks any basis in law or fact.

2b. The standard of review for economic benefits is a de novo standard as the Courts have consistently substituted their judgment regarding the benefits of economic activity.While the general standard of review for agency actions is an arbitrary and capricious standard of review, Courts have consistently held agencies to a much tighter level of review of economic benefits in the NEPA process, as the court makes their own conclusions regarding the accuracy of review without deference to agency findings. Relevant court rulings addressing economic analysis and benefits have concluded:

“an EIS serves two functions. First, it ensures that agencies take a hard look at the environmental effects of proposed projects. Second, it ensures that relevant information regarding proposed projects is available to members of the public so that they may play a role in the decision making process. Robertson, 490 U.S. at 349, 109 S.Ct. at 1845. For an EIS to serve these functions, it is essential that the EIS not be based on misleading economic assumptions.”2

The Court discussed the significance of economic benefits and analysis in planning as follows:

“Misleading economic assumptions can defeat the first function of an EIS by impairing the agency’s consideration of the adverse environmental effects of a proposed project. See, South La. Envtl. Council, Inc. v. Sand, 629 F.2d 1005, 1011-12 (5th Cir.1980). NEPA requires agencies to balance a project’s economic benefits against its adverse environmental effects. Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Comm. v. United States Atomic Energy Comm’n, 449 F.2d 1109, 1113 (D.C.Cir.1971). “3

The level of accuracy of the hard look at economic analysis applied by the Court in the Hughes River decision is significant as the Hughes River Court invalidated an EIS based on an error in economic contribution calculations of approximately 32%.4 As more specifically addressed later in this appeal, economic contributions of recreational usage and related jobs expanded to more than 7 times original estimates between the draft and final RMP but the management of the more than 1,894 sites identified for cultural resource management simply never changes in terms of total sites, allocation of these sites to use categories or management standards that are associated with the usage categories. The Organizations submit that any assertion that a 7 times expansion of recreational spending and jobs would not impact these issues would completely factual and legal basis as recreational usage is directly impacted by the closure of 1,894 football field sized sites around the field office.

3a. Information regarding ineligible historical sites has been illegally withheld from the public in the GJFO process and the FRMP must be reversed.The Organizations submit that there is a preliminary evidentiary question of law for this tribunal to resolve prior to proceeding to the substantive claims in the appeal, which is

“May a NEPA review be confirmed when inventory information that must be provided to the public for 966 sites that are subject to mandatorily closure has been claimed to be confidential?”

The Organizations submit that as a matter of law the 51% of the possible cultural sites identified as “ineligible for listing” on the National Register (966 of 1,854 sites identified) are no longer subject to confidentiality provisions of a §106 designation. Rather as a matter of law, this inventory information must be released to the public. The continued failure to provide this information has materially and directly impacted the Organizations ability to meaningfully comment or review the proposed mandatory closures for these areas. The Organizations vigorously assert that the agencies must not be allowed to flagrantly disregard regulations waiving claims of confidentiality to avoid the public review process of NEPA and then hide behind claims of confidentiality on appeal. Such a position is both illegally and morally reprehensible.

As a matter of law, the confidentiality provisions of a §106 review are ineligible to sites that are found ineligible for management and are being addressed in the NEPA process. The Organizations vigorously assert that determining a site is “not eligible” for management renders the site outside the protection of §106 as information must be disclosed in the public process of analysis of multiple uses under NEPA. Under historic preservation laws, the release of information regarding the determination that a site is “ineligible” for listing is mandatory. These regulations specifically provide:

(1) No historic properties affected. If the agency official finds that either there are no historic properties present or there are historic properties present but the undertaking will have no effect upon them as defined in § 800.16(i), the agency official shall provide documentation of this finding, as set forth in § 800.11(d), to the SHPO/THPO. The agency official shall…. make the documentation available for public inspection prior to approving the undertaking. (i) If the SHPO/THPO, or the Council if it has entered the section 106 process, does not object within 30 days of receipt of an adequately documented finding, the agency official’s responsibilities under section 106 are fulfilled.5

§106 experts clearly identify the scope of the §106 process and confidentiality in relation to continued analysis of sites under NEPA as follows:

“You may, of course, come out of the identification process having found nothing that’s eligible for the National Register. In this case, you determine that no historic properties will be affected and give the SHPO/THPO and other consulting parties thirty days to comment, and if the SHPO/THPO does not object within that time, your through with Section 106 review. You may have to deal with ineligible properties under NEPA or other laws, but section 106 review is done.”

Representatives of the Organizations have repeatedly and vigorously requested supporting documentation to address the basis for mandatory closures of all historical sites, even those found 966 sites found ineligible, in the GJFO planning process. These requests have taken many forms, including formal FOIA requests. When these written requests were declined based on confidentiality and predecisional documents claims, the Organizations sought to obtain information in a more informal manner, such as requesting on site visits with staff to trails in historic areas during quarterly meetings with the GJFO. The Organizations submit that the information on historical sites was not predecisional as the §106 process is entirely separate from NEPA and concludes with determinations regarding eligibility of sites as a matter of law. Even these informal site visits have been declined due to confidentiality issues.

The Organizations submit that additional documentation addressing eligible sites could have been easily redacted from the complete inventory of cultural sites to remove confidential information regarding eligible sites and significant additional information regarding ineligible sites could have been provided to support the mandatory closures of areas in the NEPA process that were found ineligible for listing. The GJFO chose not to proceed in this manner and instead chose to create a simplistic summary worksheet in violation of regulations requiring the release of this information. The Organizations vigorously assert that the fact pattern in the Block decision, discussed subsequently, precludes this type of summary worksheet and withholding of underlying inventory information.

The Organizations submit results in the application of §106 confidentiality provisions in a manner that allows continued claims of confidentiality for ineligible sites is a direct violation of federal law. The Organizations are simply unaware of any provisions outside §106 that provide for unilateral claims of the confidentiality of sites or artificial limitations on the scope of review by agency in the NEPA process. Such a position would directly conflict with one of the foundational hallmarks of NEPA analysis, mainly a full and fair public process of the agency decision making process regarding mandatory closures around cultural sites. The Organizations further submit that mandatory balancing of usages regarding closures of ineligible sites simply cannot be legally sufficient in a multiple use balancing decisions with evidence provided in Appendix I of the FRMP. That information is routinely limited to descriptions of “open lithic” or “open camp” that “needs data or assessment” for sites that are ineligible for listing. These descriptions are additionally insufficient to justify the limited range of management alternatives that are provided for sites that are ineligible for listing.

The Organizations further submit that the prejudice to the public resulting from the illegal assertion of confidentiality cannot be mitigated by an in camera review of the documents with the court to review the basis and scope of redaction of information. There simply has been no information provided to review in this manner and undertaking such a review would be a violation of the mandatory requirements of public disclosure of this information. The Organizations submit that failing to provide the basis for mandatory closures to all surface disturbing activities being imposed on the 966 sites found ineligible for listing is a reversible decision on appeal.

3b. Withholding of information on ineligible cultural sites is a per se violation of NEPA requirements.In addition to the withholding of specific information on the 966 ineligible sites directly violating historical preservation laws, such a position violates both the spirit and requirement of sufficient public involvement in NEPA analysis and relevant case law applying these NEPA standards. Courts have routinely reversed NEPA decisions when there is a failure to provide supporting documents for public review. Agencies that seek to provide a worksheet instead of the underlying documentation do so at their peril. In a NEPA proceeding, education and involvement of the public as to the basis and process of analysis utilized by the agency for decisions is one of the hallmarks of the proceeding. The Organizations submit that public involvement as a foundational principal in the NEPA process is woven throughout those regulations to such a degree as to make specific citation to each provision impossible. However, the Organizations submit that there are two specific provisions of the NEPA regulations that directly relate to the proper levels of public involvement in agency documentation as to warrant specific discussion.

NEPA provisions specifically address the need to make related agency materials available for public review as part of the NEPA process. These provisions explicitly and clearly provide:

“If another decision document accompanies the relevant environmental documents to the decisionmaker, agencies are encouraged to make available to the public before the decision is made any part of that document that relates to the comparison of alternatives.”6

NEPA regulations further specifically address underlying documents and the broader scope of disclosure of these documents in the NEPA process as follows:

(f) Make environmental impact statements, the comments received, and any underlying documents available to the public pursuant to the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act (5 U.S.C. 552), without regard to the exclusion for interagency memoranda where such memoranda transmit comments of Federal agencies on the environmental impact of the proposed action. 7

Courts reviewing NEPA analysis where critical inventory information has been withheld have uniformly held not only EIS, but also the data and documents on which EIS rely, must be available and accessible to the public. If such materials are not readily available to the public, an agency is barred from invoking them in Court in defending the adequacy of the analysis and that failure to disclose this information is a reversible error under general NEPA analysis. The Courts have explicitly stated in matters addressing the intentional withholding of supporting documents in the NEPA process that:

“Second, in any event we conclude that the worksheets cannot be fairly considered as part of the RARE II Final EIS. It is settled in this circuit that any supporting data or studies expressly relied upon in an EIS must be “available and accessible” to the public. Trout Unlimited, Inc., 509 F.2d at 1284. The WARS worksheets, however, are scattered all over the country in various Regional Foresters’ offices, dooming any practical attempt to review comprehensively the worksheets. Given this inaccessibility, the worksheets may not be considered in determining the RARE II Final EIS’s adequacy. “8

The Organizations would be remiss if the similarity of process related issues between the situation presented in the Block Court decision and the GJFO handling of cultural resources inventory were not addressed. In both matters, site specific inventory information was withheld in favor of a worksheet style scoring summary of factors being provided to the public to outline the factors alleged to be used in balancing usages in the NEPA process. The Block Court decision directly addresses this policy as follows:

“Second, little explanation is given to justify the numerical values given these variables. The Final EIS, for instance, offers no explanation of how resource output levels were assigned to each area. The EIS states that the levels “may appear to have been arbitrarily selected but, in fact, represent a realistic establishment of acceptable resource trade-offs to provide various alternative approaches.” RARE II Final EIS at 21. The Final EIS, however, does not explain what the tradeoffs were or why they were considered acceptable or realistic. California v. Bergland, 483 F.Supp. at 490. Rather than utilizing the Final EIS as an instrument for airing the issue of resource demand, the Forest Service instead shrouded the issue from public scrutiny behind the claim ofadministrative expertise.”9

The Organizations submit that as further information regarding the nature of sites simply is not confidential, as the Agency completely lacks authority to unilaterally assert privilege in a NEPA proceeding.

As a matter of law, GJFO is now precluded from relying on any additional information to substantiate the basis for their decisions to preclude all usage of these 966 areas. The Organizations vigorously assert that when the entirety of evidence to support the mandatory closures of any area and artificially limited range of Alternatives for the management of ineligible areas under multiple use tenants is “open camp” or “open lithic” that “needs data or assessment” , such a position is insufficient as a matter of law. The Organizations submit the unilateral and illegal decision to continue to treat ineligible sites as confidential directly evidences the priority position that these sites have been continuous provided in the NEPA balancing of multiple uses. The Organizations vigorously assert that the illegal withholding of information regarding ineligible sites has materially and directly impaired the publics ability to comment on the decision making process and address site specific issues on appeal.

As no information regarding cultural sites has been provided under an illegal assertion of confidentiality, the agency must be precluded as a matter of law from relying on any additional documentation to support management of these sites. Such reliance would be a direct violation of NEPA requirements. The Organizations submit that this preclusion applies to all phases of review, including a possible in camera review of evidence by the Court. The Organizations submit that the continued application of confidentiality claims under §106 to ineligible sites is a violation of NEPA planning requirements of a full and fair public involvement in the decision making process. The Organizations submit that any additional documentation on this issue is precluded from the administrative record as a matter of law and that as a matter of law both the decision to apply mandatory closures and a limited range of alternatives for management of these sites are unsustainable under multiple use management requirements.

4. Management of possible cultural resource sites is governed by multiple use principals under federal law.The Organizations believe a review of the statutory management requirements for cultural sites is highly relevant to this appeal. The Organizations do not contest that the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 10(“NHPA”)provides for an extensive process that must be undertaken in order to consult with Native Americans, identify and inventory cultural sites on public lands

to be followed. The NHPA provides extensive guidance for the cultural site inventory process and general objectives, but the NHPA stops short of addressing management of these sites. Rather NHPA is largely procedural in nature and does not mandate a specific outcome in the management process as it provides as follows:

” It is the policy of the Federal Government, in cooperation with other nations and in partnership with States, local governments, Indian tribes, Native Hawaiian organizations, and private organizations and individuals, to—

- use measures, including financial and technical assistance, to foster conditions under which our modern society and our historic property can exist in productive harmony and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations;

- provide leadership in the preservation of the historic property of the United States and of the international community of nations and in the administration of the national preservation program;

- administer federally owned, administered, or controlled historic property in a spirit of stewardship for the inspiration and benefit of present and future generations;

- contribute to the preservation of nonfederally owned historic property and give maximum encouragement to organizations and individuals undertaking preservation by private means;

- encourage the public and private preservation and utilization of all usable elements of the Nation’s historic built environment; and

- assist State and local governments, Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations, and the National Trust to expand and accelerate their historic preservation programs and activities. “11

Congress did not specifically address management of cultural sites until FPMA was adopted in 1976. Here Congress clearly stated that cultural resources are a factor to be balanced as a multiple usage of public lands. Congress has repeatedly had the opportunity since adopting FLPMA to exclude cultural resources from this balancing process and chose not to make such an amendment. Rather Congress has repeatedly and clearly stated the requirement that cultural resource protection be governed by multiple use requirements. The management of cultural resources on public lands is specifically addressed in FLPMA which states as follows:

“(8) the public lands be managed in a manner that will protect the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource, and archeological values; that, where appropriate, will preserve and protect certain public lands in their natural condition; that will provide food and habitat for fish and wildlife and domestic animals; and that will provide for outdoor recreation and human occupancy and use;” 12

Several years later, Congress had the opportunity to change cultural resources management standards and alter the balance of multiple use requirements in relation to cultural resources management. Again, Congress chose not to make such an amendment by clearly stating in the Archaeological Resource Protection Act as follows:

“SEC. 12. (a) Nothing in this Act shall be construed to repeal, modify, or impose additional restrictions on the activities permitted under existing laws and authorities relating to mining, mineral leasing, reclamation, and other multiple uses of the public lands.”13

The Organizations submit that cultural resource management is a two step process: 1: creation of an inventory and allocation of sites to use categories; and 2: balancing protection of inventoried sites with multiple usages of these areas. The Organizations vigorously assert that the Grand Junction FRMP clearly has placed the management of cultural resources ahead of all other multiple uses and has failed to balance impacts from cultural resource protections with other activities by managing each site as a trustee as evidenced by the fact that the only sites excluded from management were actually impossible to manage as they had been destroyed by fire or previously sold. The Organizations submit that this failure to balance multiple uses is directly evidenced by the fact that economic contributions from recreational activities expanded to more than 7 times original estimates between the draft and final RMP and absolutely no changes were made to the total number of cultural sites, allocation of cultural sites to management categories, management standards for each category of usage or the fact that eligibility for the national register simply was not addressed.

Numerous BLM manuals issued relative to the application of these Congressional mandates and outlining proper implementation of the required balancing of multiple uses with cultural resources management have specifically stated clarified the lack of a priority management position for cultural resources in relation to other multiple uses as follows:

“B. The Nature of BLM’s Tribal Consultation under Cultural Resource Authorities. In contrast, BLM’s tribal consultation under cultural resource authorities generally does not involve either Indian lands or trust assets, and consequently there is no ownership-based presumption that a tribe’s input will compel a decision that fulfills the tribe’s requests or resolves issues in the tribe’s favor. The BLM manager must make an affirmative effort to consult, and must consider tribal input fairly; but decisions are based on multiple-use principles and a complex framework of legal responsibilities, not on property principles and the obligations of the trustee to the trust beneficiary.14

C. Apart from certain considerations derived from specific cultural resource statutes, management of cultural resources on the public lands is primarily based on FLPMA (see .O3H), and is governed by the same multiple use principles and the same planning and decision making processes as are followed in managing other public land resources.”15

It is the Organizations position that consideration of tribal input applies both ways, as cultural resources must be balanced in multiple use and multiple usage must not be completely excluded from cultural resource sites. The Organizations submit that the GJFO applies cultural resource concerns in a manner consistent with a trustee and has simply ignored that decisions must be made on multiple-use principles and a complex framework of legal responsibilities.

The Organizations submit that the position of the Council on Environmental Quality (“CEQ”) in recently released guidance documents for cultural sites is highly relevant to this appeal. Newly released CEQ guidance documents provide the following statement:

“Traditional cultural landscapes describe an area considered to be culturally significant. They can and often do embrace one or more of the property types defined in the NHPA: districts, buildings, structures, sites, and objects. It is important to note that the challenges associated with the management of such sites, and their potential size, do not excuse the consideration of their significance.”16

It is the Organizations position that challenges in site specific management can no more justify the ignoring of cultural resources in multiple use planning as it can justify the exclusion of all multiple uses from cultural resource areas. Again the Organizations submit that the GJFO RMP manages cultural resources as a trustee would manage a trust rather than a balanced interest in multiple usage as directly evidenced by the fact that the only sites released from further management were either sold by BLM previously or destroyed by fire.

5a(i). The range of alternatives has been inappropriately limited for cultural resource management as benefits of a designated trail system are never addressed.The Organizations vigorously assert that the determination that all cultural resources will be managed as a trustee would manage a trust rather than in compliance with multiple usage mandates has directly impacted the range of alternatives that were provided to the public in the draft RMP. The Organizations submit this failure is arbitrary and capricious and a per se violation of NEPA planning requirements. CEQ regulations specifically address the proper range of alternatives in a NEPA analysis as follows:

“§ 1502.14 Alternatives including the proposed action. This section is the heart of the environmental impact statement. Based on the information and analysis presented in the sections on the Affected Environment (§ 1502.15) and the Environmental Consequences (§ 1502.16), it should present the environmental impacts of the proposal and the alternatives in comparative form, thus sharply defining the issues and providing a clear basis for choice among options by the decisionmaker and the public. In this section agencies shall:

(a)Rigorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives, and for alternatives which were eliminated from detailed study, briefly discuss the reasons for their having been eliminated.

(b)Devote substantial treatment to each alternative considered in detail including the proposed action so that reviewers may evaluate their comparative merits.”17

Newly released CEQ guidance documents address the relationship of NEPA and proper satisfaction of the informational requirements and historic preservation statutes clearly identify the range of alternatives and data quality for cultural resources to be provided in an EIS as follows:

“The CEQ regulations require agencies to describe the environment, including cultural resources, likely to be affected by the proposed action and alternatives, and to discuss and consider the environmental effects of the proposed action and alternatives, so decision makers and the public may compare the consequences associated with alternate courses of action. Data and analysis vary depending on the importance of the impact, and the description should be no longer than necessary to understand the effects of the alternatives, with less important material summarized, consolidated, or referenced.”18

The Organizations are deeply concerned that the FRMP addressed cultural resource protection by adding 15 new standards for the management of these areas.19 These 15 new standards are exactly the same for every alternative, causing the Organizations to believe there was simply no intent to balance usages as there was 45 different opportunities to balance usage and none were ever taken. These standards simply manage these areas as trustee would manage a trust. At no point is there any language that even references possible flexibility for balancing of multiple uses in these standards.

The Organizations submit that there are clearly Alternatives for management of cultural resources that have not been explored in NEPA analysis as the determination was made early in the management process that cultural resources would be managed under standards of a trustee managing a trust rather than as a balanced usage. The Organizations further submit that proof of viable alternatives not being provided is directly evidenced by the fact that cultural resource management standards in the GJFO FRMP result in standards that Congress has specifically determined are not appropriate for cultural sites, such as mandatory closures around routes and are simply unrelated to the historical usage of the site.

The Organizations submit that the limited range of alternatives provided for the management of OHV travel in association with cultural resource sites in the GJFO RMP becomes immediately apparent when GJFO management is compared to national BLM guidance for the use of OHV’s in association with possible cultural resource sites. The national BLM guidance issued to supplement manual 8110 provides for a wide range of management alternatives to allow for continued OHV usage around these areas. 20 The Memorandum starts the analysis by identifying categories of usage that are outside the cultural resource management issue as follows:

“Potential for Adverse Effect: The potential effects of proposed designations differ according to the extent of anticipated change in OHV use.

A. Proposed designations that will not change or will reduce OHV use are unlikely to adversely affect historic properties and will require less intensive identification efforts. These include designations that (1) allow continued use of an existing route; (2) impose new limitations on an existing route; (3) close an open area or travel route; (4) keep a closed area closed; or (5) keep an open area open.”

Given that 40% of the GJFO remains managed as an open riding area designation and clearly there are routes that could be kept open, the Organizations submit that there are clearly alternatives that could have been developed to preserve access. No analysis or discussion is ever provided as to why these alternatives were found insufficient to protect cultural resource sites. Such an alternative would be highly viable in areas that lack data or are ineligible for listing on the National Register, which encompasses 78% of the sites identified in the inventory. The Organizations submit this complete lack of analysis is direct evidence of the determination that all cultural resources would be managed as a trustee managing a trust rather than as a balanced multiple use of public lands. The management alternatives provided in national BLM memorandum clearly could have been reflected under one alternative of the 15 new categories of management. This simply was not done.

In addition to the above landscape level discussion of alternatives for these areas, the Memorandum continues with an extensive discussion of the relationship of travel management standards to the value of the historic site and alternative that are available to avoid closure of the route. These provisions specifically provide:

“D. Development of Planning Alternatives: Selection of specific road and trail networks and imposition of other use limitations, should avoid impacts on historic properties where possible. In accordance with 43 CFR 8342, existing cultural resource information must be considered when choosing among the range of alternatives for the design of a planning area travel system, including the potential impacts on cultural resources when determining whether each of the routes or areas in a planning area should be designated as open, limited, or closed. Sensitive resource areas may be protected through rerouting, reconstruction, and new construction, limitations on vehicle type and time or season of travel, in addition to closure. Evaluation of routes or areas to be designated as closed to protect cultural resources may be based on existing inventory information and should not be postponed until additional information is acquired. ”

The Organizations submit that any position asserting mitigation of impacts by rerouting, reconstruction and limitations was not possible at all of the 1,894 sites identified in the inventory clearly lacks factual or rational basis. The Organizations submit that the complete lack of factual basis in such an assertion clearly evidences that alternatives that were available and simply never provided for public comment or analysis for reasons that are unclear.

5b(i). Determining the proper scope of protection and implications to multiple usage simply cannot be measured as 78% of sites need data or are ineligible for listing.As more specifically addressed later in this appeal, the impacts of economic contributions flowing from spending and jobs was expanded by more than 7 times from draft to final yet no explanation of why the allocation of cultural resources was not impacted by this change has even been attempted. The Organizations submit that even without this change the lack of alternatives for management of possible cultural sites is immediately apparent when the allocation of sites to use categories and eligibility of sites is reviewed. Every alternative in the draft and final EIS had the same management standards associated with usage categories. These usages are summarized as follows:

| Use Category |

Mandatory closure |

# of sites in Draft |

# of sites in Final |

| Scientific |

100m |

1,574 |

1,574 |

| Conservation |

100m |

4 |

4 |

| Traditional |

200m |

135 |

135 |

| Public usage |

100m |

95 |

95 |

| Experimental |

n/a |

79 |

79 |

| Discharge |

n/a |

7 |

7 |

| TOTAL |

|

1,874 |

1,874 |

After a summary of the eligibility analysis in appendix I is prepared, additional basis for concern regarding the limited range of alternatives becomes immediately apparent as 78% of sites are identified as ineligible for listing or needing data. That summary of appendix I eligibility provides the following conclusions:

| Eligibility of site for Listing |

Draft |

Final |

| Actively on National Register |

3(.1%) |

3 (.1%) |

| Possibly eligible for listing |

398 (21%) |

398 (21%) |

| Lacking data/assessment |

520 (27%) |

520 (27%) |

| Not Eligible |

966 (51%) |

966 (51%) |

| Released from further |

7 (.3%) |

7 (.3%) |

| Total |

1,894 |

1,894 |

These eligibility criteria in no way relate to the classification of usage, again causing the Organizations to submit that the lack of data in no way was addressed in planning. Clearly the lack of data or ineligibility would warrant a higher percentage of these sites being in lower protection areas if balancing of usages had occurred. That simply did not happen. There simply can be no comparison of impacts from various management alternatives as none have ever been provided despite the fact that 78% of sites have been identified as ineligible for protection on the National Register or completely lacking data for analysis. As 78% are lacking data or ineligible for listing there is a high degree of discretion in decision making that has been performed on these sites but no analysis or information has been provided to the public to provide insight into this process and how a proper balance of multiple usage was insured. Again, only 7 sites being released from management due to the impossibility of future management is a significantly different standard that a balanced approach to management of areas suitable for further management.

While 78% of sites simply have no data or are found ineligible for listing all sites is subjected to a minimum 100 m exclusion of all surface disturbing activity.21135 sites are governed under a 200m mandatory closure to surface disturbing activity.22 The term “surface disturbing activity” is simply never defined in the GJFO RMP, causing further concern about the ability to consistently address impacts from management. How can there be any argument that usages were balanced for these areas when the plan completely fails to define what is and what is not a permissible usage. The term “surface disturbing activity” is the basis for active discussions in Sage Grouse management which relies on the following definition:

“Surface-disturbing activities. An action that alters the vegetation, surface/near surface soil resources, and/or surface geologic features, beyond natural site conditions and on a scale that affects other public land values. Examples of surface disturbing activities may include: operation of heavy equipment to construct well pads, roads, pits and reservoirs; installation of pipelines and power lines; and the conduct of several types of vegetation treatments (e.g., prescribed fire, etc.). Surface disturbing activities may be either authorized or prohibited.”23

Federal law has mandated protection of historical sites only if they are significant or important, and mandating some type of site specific review before management standards can be determined. While additional sites may be managed under agency discretion, all management decisions must be balanced as a multiple usage of public lands and not as a trustee would manage a trust. The failure to balance multiple use in proposed cultural areas simply cannot be accurately addressed in this appeal/protest as much of the information needed to create a meaningful appeal/protest on this issue has simply been withheld. The failure to provide this information makes any appeal of specific impacts from the limited range of alternatives very difficult if not impossible. The Organizations submit that a designated trail system in these areas would effectively mitigate impacts to lesser important sites and make complete closure unnecessary.

5b(ii). Management standards provide no flexibility to address localized geographic issues which will result in significant unintended economic impacts.The Organizations submit that the failure to balance multiple uses is also evidenced in the FRMP failure to provide any flexibility in management standards for localized issues. This lack of flexibility will cause the loss of opportunities in areas that are completely unrelated to the possible cultural sites, as many areas of the GJFO are exceptionally rugged and have limited areas where routes may be placed. While the access point may be in a bottleneck opportunities that would be lost by closing the bottleneck would be significant. It is simply unreasonable to assert that access can be preserved if a cultural site is in the bottom of a canyon that is also the location of an important route using the canyon bottom. Closure of the 100 or 200 meters around the site could block a route and preclude access to a large areas of the GJFO that are miles from the cultural site for a huge number of activities. Rerouting this route to the steep canyon wall would simply be impossible. Again this situation directly evidences the failure to properly balance site specific issues as part of the multiple use process.

5c(i). Landscape level comparisons directly evidence the impacts of managing cultural sites ina manner similar to a trustee managing a trust.The lack of factual basis and balancing of multiple uses in the GJFO conclusions of a balanced usage for cultural site management provided in the appendix I is confirmed as the appendix notes that only 7 (.3%) sites of the 1,894 inventoried for management were found to lack significance. All other sites were allocated to a specific level of use management, indicating some level of significance or importance in the site. The Organizations vigorously question this step, as most sites clearly do not meet the criteria for further management as they are identified as open camps or open lithics. The Organizations simply do not believe that any campsite or unidentified stone formation, no matter how consistently used hundreds of years ago, will ever meet the statutory requirements of significance or importance to justify listing on the national register of historical places. The Organizations believe this is facial evidence that the application of the “significance” standard was entirely too loose and allowed many sites that truly are not significant to be managed as significant sites.

The failure to properly balance usages and importance of sites results in the positioning of the Grand Junction area as probably the most historically significant area if the number of historic sites was a metric of this analysis. Currently, there are 50 sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the GJFO planning area. GJFO RMP seeks to expand listing and management to 1,894 sites. The scope of the impact of this standard on the GJFO planning process is simply immense. A review of the appendix for cultural sites reveals GJFO has identified 1,894 sites on the planning area that meet the criteria for designation on the National Register of Historic Places. This level and density of cultural sites in any location is simply unprecedented when compared to the scope of the National Register of Historic Places in Colorado, as currently in Colorado there are only 1,430 sites on the National Register of Historic Places.24The overwhelming portion of these 1,894 historic sites are located in towns, villages and other municipalities and outside the scope of analysis in federal planning. Clearly this position lacks factual or legal basis when compared to the fact that only 1,420 sites have been identified in Colorado since the creation of the National Register.

Of the sites currently on the National Register in Colorado, only 50 are located in the vicinity of the GJFO and all are restored homes, bridges, municipal buildings or churches none of which are under BLM management. 25The GJFO position is that the national register in Garfield and Mesa County should be expanded by a factor of 38x. This position completely lacks factual and legal basis. The Organizations believe that any review of these sites by the Historic Register Committee would result in the immediate decline of almost every site as they are neither significant or important also would position Garfield and Mesa counties as the most historically important counties in the nation. The Organizations submit that position simply lacks factual and legal defensibility.

The Organizations believe a comparison of the total number of sites identified by the GJFO for mandatory protection as cultural sites to the number of cultural sites currently managed in Washington DC is highly relevant to the appeal/protest. Washington DC only has 569 sites on the National Register and the Organizations submit that any assertion that Grand Junction Colorado has 3.5x more sites worthy of protection than Washington DC facially evidences the arbitrary and capricious nature of the decision. Again such a position lacks factual and legal defensibility.

5c(ii). The imbalance of multiple uses is supported by the amount of trails lost due to Endangered Species issues and cultural resources protection.Prior to addressing specific management standards the Organizations believe a review of the mileage of routes lost is highly relevant. FRMP identifies that 1,296 miles of routes have been lost for cultural and wildlife issues.26 The FRMP further identifies that the total mileage of routes lost for sensitive and endangered species as 679.527. Based on this analysis, the conclusion must be reached that 617 miles of routes have been lost solely due to cultural resource concerns prior to the application of any site specific management requirements. The Organizations submit that the fact there is this level of consistency on the basis of closures between endangered species habitat and cultural resources is an indication of an imbalance in the analysis of cultural resources, which remain subject to multiple use planning requirements.

5c(iii). Mandatory closures of all possible cultural sites conflicts with national objectives for the utilization of historical sites.The Organizations submit that the mandatory closures of all historical sites to surface disturbing activities in the GJFO RMP directly conflicts with management by NPS for historical sites. In contrast to the GJFO mandatory closures, the website for the National Register of Historic Places actively identifies 9,495 sites nationally that are vacant and solicits usage as these sites which may be an ideal location for your next home or business.28The arbitrary and capricious nature of the GJFO management is immediately apparent when compared to these utilization efforts as living in a property is probably a surface disturbing activity.

Additionally, the National Trust for Historic Preservation provides links to specialized realtors who specialized in connecting homes on the national register with potential buyers.29 The states of New Hampshire, Arkansas historic preservation offices facilitate the purchase of historic homes as primary residences. The Organizations would be remiss if they did not note that residing in a historic property is probably a surface disturbing activity and would now be prohibited under GJFO management standard. Again these programs directly evidence are the kind of multiple use impacts that weigh heavily against imposition of blanket landscape level closures and the arbitrary and capricious nature of the determination that surface disturbing activities must be prohibited as there is a direct conflict with these programs and GJFO management.

6a(i). GJFO management of cultural properties violates Federal law requirements of protection of sites that are important or significant.The Organizations believe the protection of significant cultural sites is an important planning criteria. While this is an important planning criteria, the Organizations are aware that all historical sites are not significant and cannot be saved for a variety of reasons. The requirement of “significance” is an important factor in determining the proper levels of management and analysis of historical sites in the planning process. Prior to addressing the facial violations of federal law that are present in the FRMP standards for cultural sites, the Organizations believe a review of relevant federal statutes is warranted as these statutes provide exceptionally clear management standards. Federal law governing cultural resources provides a general standard to address cultural resources as follows:

“The head of any Federal agency having direct or indirect jurisdiction over a proposed Federal or federally assisted undertaking in any State shall, prior to the approval of the expenditure of any Federal funds on the undertaking or prior to the issuance of any license, as the case may be, take into account the effect of the undertaking on any district, site, building, structure, or object that is included in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register.”30

The Organizations again submit that §106 provides an inventory methodology to insure cultural resources are balanced in multiple usage decision making and provides no priority for these sites in the multiple use process. Pursuant to the rules and regulations promulgated under §106, the “significance” of the cultural site and resulting eligibility of a site for designation on the National Register is a primary factor in determining if there is required management to be addressed in planning. The CFR provisions specifically provide:

“(c) Evaluate historic significance. (1) Apply National Register criteria. In consultation with the SHPO/THPO and any Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization that attaches religious and cultural significance to identified properties and guided by the Secretary’s Standards and Guidelines for Evaluation, the agency official shall apply the National Register criteria (36CFR part 63) to properties identified within the area of potential effects that have not been previously evaluated for National Register eligibility. The passage of time, changing perceptions of significance, or incomplete prior evaluations may require the agency official to reevaluate properties previously determined eligible or ineligible. The agency official shall acknowledge that Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations possess special expertise in assessing the eligibility of historic properties that may possess religious and cultural significance to them.

(2)Determine whether a property is eligible. If the agency official determines any of the National Register criteria are met and the SHPO/THPO agrees, the property shall be considered eligible for the National Register for section 106 purposes. If the agency official determines the criteria are not met and the SHPO/THPO agrees, the property shall be considered not eligible. If the agency official and the SHPO/THPO do not agree, or if the Council or the Secretary so request, the agency official shall obtain a determination of eligibility from the Secretary pursuant to 36 CFR part 63. If an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization that attaches religious and cultural significance to a property off tribal lands does not agree, it may ask the Council to request the agency official to obtain a determination of eligibility.”31

The need for findings regarding the “significance” or “importance” of a site to trigger mandatory management of historical places are specifically outlined in the BLM manual in a manner that is consistent with federal law. The manual specifically states:

“E. The National Register Criteria. A district, site, building, structure, object, traditional cultural property, historic landscape, or discrete group of thematically related properties, that represents America’s history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, or culture may be eligible for the National Register. To be judged eligible, a property must possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association, and must meet at least one of the following criteria:

- Property is associated with an event or events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of America’s history. (Corresponds to 36 CFR 60.4 criterion “a”.)

- Property is associated with the lives of persons significant in our past. (Corresponds to 36 CFR 60.4 criterion “b”.)

- Property embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or represents the work of a master, or possesses high artistic value, or represents a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction. (Corresponds to 36 CFR 60.4 criterion “c”.)

- Property has yielded or may be likely to yield information important in prehistory or history. (Corresponds to 36 CFR 60.4 criterion “d”.)”32While the lack of importance or significance does not preclude management, these factors clearly must relate to the level of management and usage of sites. Logically lesser significant sites would be allocated to usage categories with lower levels of protection. In the GJFO FRMP that simply is not the case.

The Organizations believe the GJFO has completely erred in its determination that every site now and in the future will satisfy the “significance” factor and permit additional management. As previously noted the findings of significance in the GJFO planning process are deeply inconsistent with the findings of significance by outside reviewers in the State of Colorado. No information is provided regarding the nature or location of cultural sites due to confidentiality requirements making any analysis difficult, if not impossible. Furthermore existing recreational usage of several sites is identified but not accounted for in planning.

The limited site specific summaries (95 of 1,894) directly evidence an overly broad application of protection for sites that are neither significant or important including:

- old road and rail beds;

- recorded telegraph lines and abandoned power lines;

- irrigation ditches on adjacent private lands;

- buried pipes and abandoned irrigation ditches;

- fences of unknown origin;

- two track roads of unknown origin and trails

The flagrant disregard for federal law and balancing multiple usage exhibited by these standards is simply astonishing and completely lacks factual or logical basis, as directly evidenced by the fact the GJFO plans to protect more site in the Field Office than are currently on the national register for the entire state of Colorado and three times as many sites as are currently in Washington DC. This standard also fails to address that many cultural experts in and around Grand junction admit that many of these marginally significant historical sites will simply never be excavated, as specifically noted in the appeal addressing wickiups. The Organizations believe that the lack of funding for such excavations is evidence of the lack of belief these areas will yield significant archeological information.

The Organizations are aware there is no mandate that a site be eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places in order to be managed as a historical site, however the ineligibility of a site for protection must be addressed in planning. Tables I-2 through I-7 of the cultural resources appendix specifically conclude most sites to be managed for scientific values related to cultural issues are found “not eligible” for inclusion on the National Register. Only 398 of 1,894 (21%) are found possibly eligible for listing. The fact that 78% of sites were identified as not eligible or needing data weighs heavily against the levels of closures that are proposed. As previously noted only 7 of the 1,894 sites inventoried were found not to need additional management as a result of their destruction or sale. Again a review of the suitability for management based on multiple usage cannot be based on the exclusion of the site from management only because it was destroyed or sold and impossible to manage.

6a(ii) . NEPA analysis requires detailed analysis of significant issues.The Organizations submit that the “significance” is a foundational tenant of NEPA analysis33 that weighs heavily against the closures proposed. The Organizations submit that the agency may not assert that a location for management is significant for purposes of a §106 analysis and then assert that the detailed analysis for proposed management of this sight is insignificant for purposes of NEPA analysis. Such a position is both legally and factually unsustainable.

6b. Mandatory closures around roads and trails results in management of these sites in violation of National Historic Trails Act requirements.The Organizations must briefly address the conflict that will result from GJFO RMP mandatory closures around roads, trails, abandoned power lines and other linear constructions and management standards for National Historic Trails. The Organizations submit that this is another area where mandatory closures directly conflict with Congressional action provided for in the National Trail System Act (“NTSA”).

The Organizations submit that the conflict with these specific Congressional actions and the management proposed by the GJFO indicates the arbitrary and capricious nature of the management standards that are provided. The arbitrary and capricious nature of the GJFO management is directly evidenced by the fact that the end result of management decisions is the corridor type closures being implemented without the checks and balances mandated by the NTSA.

While there is only sufficient information provided in the FEIS to address a small number of sites, the Organizations submit this comparison is highly relevant in addressing the failure to properly balance multiple usage of cultural sites and instead manages these cultural sites as a trustee. The GJFO trustee based management decision again creates direct conflict with management of areas that have already been identified as significant or important unlike the 1,894 sites in the GJFO planning area. Congress has repeatedly expressed concerns that historic routes and trails not serve as a barrier to multiple usage of lands surrounding the trail, despite the Congressional identification of the route as historic or significant. The Organizations submit that planners can’t simply avoid the legally identified process and then manage these areas in a manner that directly contradicts Congressional desire for the balanced usage of these areas.

Management of National Historic Trails is generally governed by the NTSA which specifically addresses multiple usage of areas adjacent to trails and how these multiple use mandates will relate to management of the trail. The NTSA provides as follows:

“Development and management of each segment of the National Trails System shall be designed to harmonize with and complement any established multiple use plans for that specific area in order to insure continued maximum benefits from the land.”34

The Organizations submit that the mandatory inclusion of multiple usage requirements in the management of these truly historical trails and routes again evidences Congressional concern regarding negative impacts to multiple uses that could result from these types of mandatory closures of long corridors. The Organizations submit that none of the routes identified in the GJFO RMP are sufficiently important or significant to warrant a discussion of possible addition to the national historic trails list, and as a result these areas are entitled to at least similar levels of protection of multiple usages. While these routes are not sufficiently important or significant enough to warrant listing, the proposed mandatory closures associated with these sites is exactly the type of management that Congress has repeatedly sought to avoid with more important routes and trails. The Organizations again submit this conflict is direct evidence of the arbitrary and capricious decision of land managers to manage cultural sites as a trustee rather than balance multiple usage of these areas.

6c(i). The failure to provide sufficient analysis of impacts from surface disturbing activity is stark when GJFO cultural processes are compared to the Northwestern Colorado Sage Grouse management efforts.The Organizations believe that the arbitrary and capricious nature of the decision that mandatory closures are required for cultural sites is again evidenced by comparison to the efforts of the BLM managing Sage Grouse Leks in Northwestern Colorado. The overlap of management concerns is significant as the site of active leks for sage grouse and location of cultural resource sites are confidential. Both issues are subject to multiple use planning until a decision is made on sage grouse status for ESA purposes. Both issues are subject to mandatory closures for surface disturbing activities. NWCO DEIS addresses these issues with literally thousands of pages of analysis, even though NWCO DEIS is addressing significantly smaller number of sites and moves away from mandatory closures for the management of leks. As a result, management of sage grouse habitat is a national issue with wide ranging input. The GJFO simply asserts the management is necessary without discussion or analysis. The explanation of the management process has resulted in management of sage grouse sites being a national issue with a large amount of input form a wide range of stakeholders. GJFO simply asserts this management is necessary without discussion of the similarity of management issues and stark contrast in analysis provided evidences the arbitrary and capricious nature of the GJFO position.

6c(ii). Cattle grazing is a serious threat to cultural sites and management of this issue simply has not been reviewed and will conflict with Sage Grouse management efforts.The Organizations submit that the arbitrary and capricious nature of the GJFO decision to close all cultural sites to surface disturbing activity is directly evidenced by the immediate conflicts that implementation of these closure standards will have with Sage Grouse management efforts in Colorado. The Organizations believe that implementation of management to exclude cattle grazing from all cultural sites will provide a stark example of this issue.

Cattle grazing has historically identified as a surface disturbing activity degrading grouse leks and habitat and is priority threat to cultural sites. This threat to cultural sites has been summarized as follows:

“It is common to find sites where structures are visible only as chunks of mortar scattered among the dung, with perhaps a tell-tale stain of clay along an alcove back wall to indicate a structure once stood there. Wherever livestock have access, surface artifacts are rare. The integrity of artifact concentrations is lost, and the artifacts themselves are not visible unless subsurface testing is done.”35

Previous cattle management efforts for the benefit of endangered species, such as the Prebles Jumping mouse, have identified that fencing is the only effective way to prohibit cattle from habitat areas. Given that fencing is the only effective manner to stop cattle incursion, this would be the major management tool for protecting cultural sites as well.

Undertaking a large scale fencing project for the protection of cultural resources would immediately conflict with management efforts currently undertaken to avoid the listing of the greater Sage Grouse in Northwestern Colorado. These efforts are seeking to minimize and remove fencing in sage grouse habitat areas due to the competitive advantage that these elevated perch areas give to predators. The NWCO sage grouse RMP applies the following standard for fencing while addressing management issues as follows:

“Where existing leases, ROWs or SUAs have had some level of development (road, fence, well, etc.) and are no longer in use, reclaim the site by removing these features and restoring the habitat.”36

The Northwestern Colorado Sage Grouse RMP provides the following management standards for fences:

“(PPH) To reduce outright GRSG strikes and mortality, remove, modify or mark fences in high risk areas within GRSG PPH based on proximity to lek, lek size, and topography (Christiansen 2009; Stevens 2011).” 37

While Sage Grouse management is highlighted, the Organizations are aware that large scale fencing activity is a major concern for many species both in terms of habitat quality, migration corridors and access to water. The NWCO Sage Grouse RMP summarizes this issue as follows:

“While the removal of livestock under Alternative C would be expected to lead to substantial improvements in herbaceous understories which would likely benefit terrestrial wildlife species in general; in all practicality, the only way to keep livestock out of these areas would be through the construction of fences. An estimated 5,000 miles of fence would need to be constructed under this alternative (see , Table 4.6, “Livestock Grazing Management-Alternative C” (p. 705), in Section 4.13, Range Management). Increased fence densities may have an impact to terrestrial wildlife species, particularly big game species. Potential impacts would depend on fence design and location (coincident with GRSG habitats).Conversely, if livestock were removed from public lands, there would be no need to maintain existing fences, particularly in areas with large, continuous tracts of publicly-owned land.”

The Organizations are completely unable to find any analysis of possible impacts to Sage Grouse habitat and other wildlife related impacts from expanded fencing of cultural areas to implement prohibitions to surface disturbing activities. The Organizations submit that given the possible listing of the Sage Grouse such a discussion would be highly relevant to the management of cultural sites, which again are only subject to multiple use planning standards. The Organizations are additionally aware that fencing 1,894 sites could also impact wildlife migration corridors, the effectiveness of winter range and many other species related issues. The Organizations submit that this conflict in basic policy direction and complete void of analysis is direct evidence of the arbitrary and capricious nature of proposed cultural resource management standards.