GMUG National Forest

Att: Forest Plan Revision

2250 South Main Street

Delta, CO 81416

Dear Sirs:

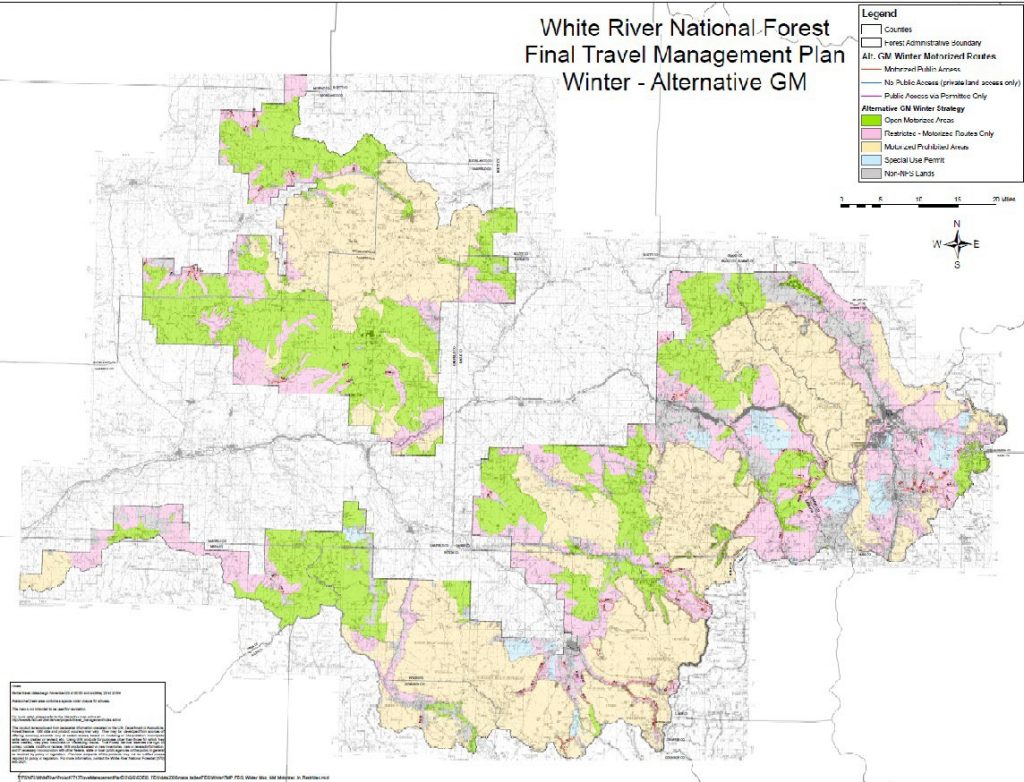

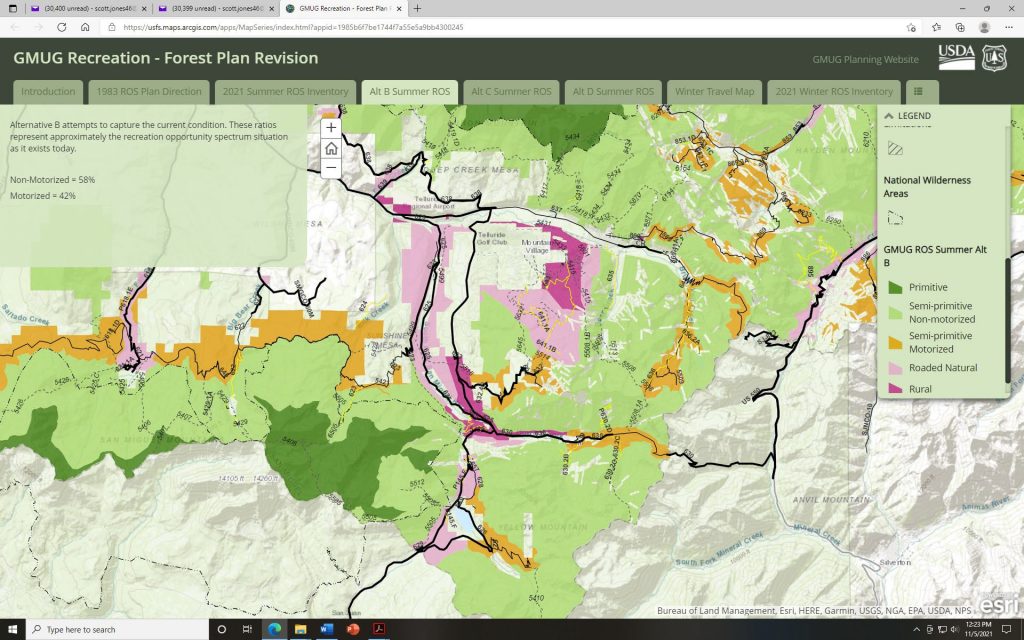

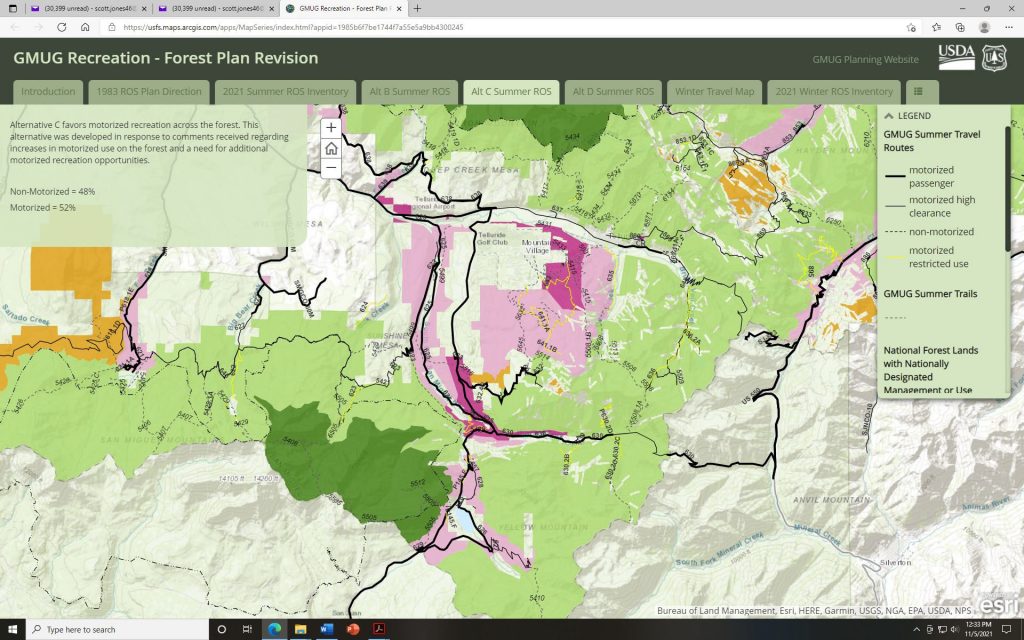

Please accept this correspondence as the comments of the above Organizations with regard to the release of the Draft GMUG Resource Plan (“hereinafter referred to as “the Proposal”). Of the Alternatives provided, Alternative C of the Proposal is the best presented but this Alternative needs significant work. A major step forward in Alternative C would be the inclusion of a landscape level management standard that creates a protective corridor around any route where the route is inconsistent with adjacent management or ROS. This is justified as every route on these maps has been through travel management multiple times. We are also concerned that in some geographic areas that Alternative B provides far better access than Alternative C, despite the assertion that Alternative C is the most intensive level of access.

We think Alternative C is the most accurate reflection of current management and are opposed to Alternative D of the Proposal. Candidly, Alternative D is so unrealistic we are going to avoid substantive discussion of many of the standards in this Alternative. Alternative D represents a huge number of areas that we have sought to protect in previous collaboratives. Often these previous NEPA collaboratives were undertaken only with significant effort and compromise from the member Organizations, is deeply disappointing to the Organizations and our members as often much of what has been proposed in citizen alternatives and sometimes alternatives in the Proposal are exactly the discussions previously raised, subsequently reviewed in NEPA and then declined to be applied.

We are unsure what Alternative A of the Proposal is attempting to reflect, as this mapping and information directly conflicts with current management designations of many areas. Alternative A is the result of the failure to accurately, consistently and completely reflect many of the site specific NEPA components, analysis and decisions that has occurred over decades on the GMUG within the existing management decision framework.

In a more troubling twist, often the inventory of site-specific analysis done within existing management designations is sought to be applied in a manner that directly conflicts with the clear scope of those efforts. Management designations are management designations and inventories are inventories and these are not concepts that can be interchanged at will in the planning process. Our concerns around the Draft RMP would include:

- We welcome the brief nature of the RMP but at this point are confused by many of the assertions on management that have been made and subsequently changed in this process such as existing ROS scope;

- We continue to struggle with the challenge regarding accurate integration and representation of existing NEPA and statutory changes that have occurred over the life of the 1983 RMP; While we appreciate efforts to provide public better information on possible impacts often this info was late and as a result, we are asking for existing motorized routes be provided a protective Corridors when these previously analyzed routes cross areas of inconsistent management;

- Inventory levels for motorized areas have reduced by 24% over the life of the 1983 plan based on subsequent NEPA when these site-specific decisions clearly and unequivocally state there was no change to management standards is within the scope of that analysis and these are existing expansion areas for motorized usage and we can’t discuss them as this information is not provided;

- Roadless area inventory of limited area characteristics are now sought to be applied as a management standard for all uses of these areas. This confuses the public in planning and will create confusion over the life of the RMP.

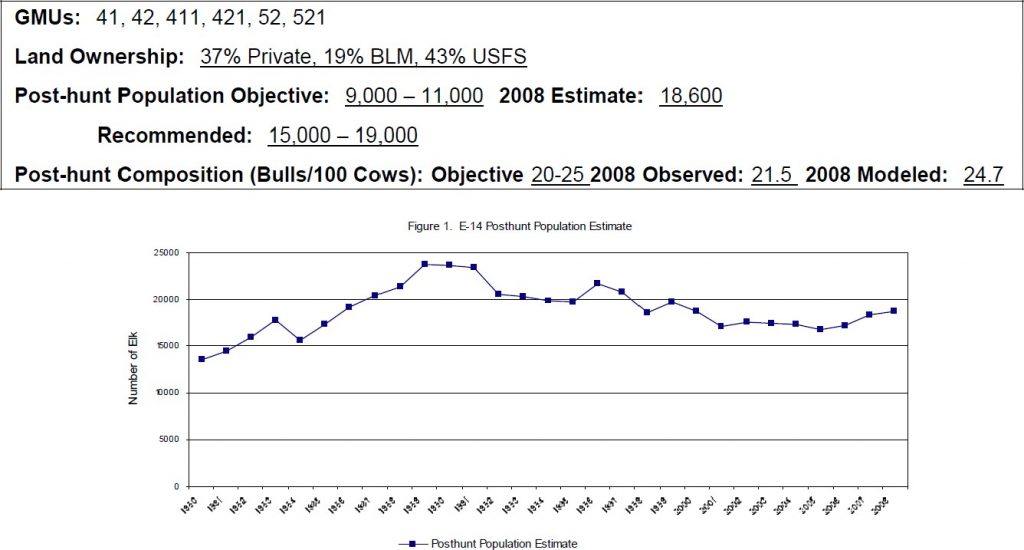

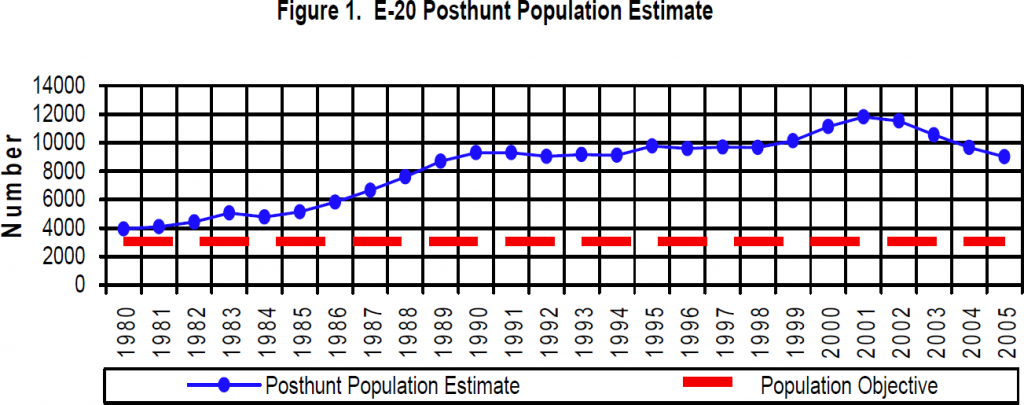

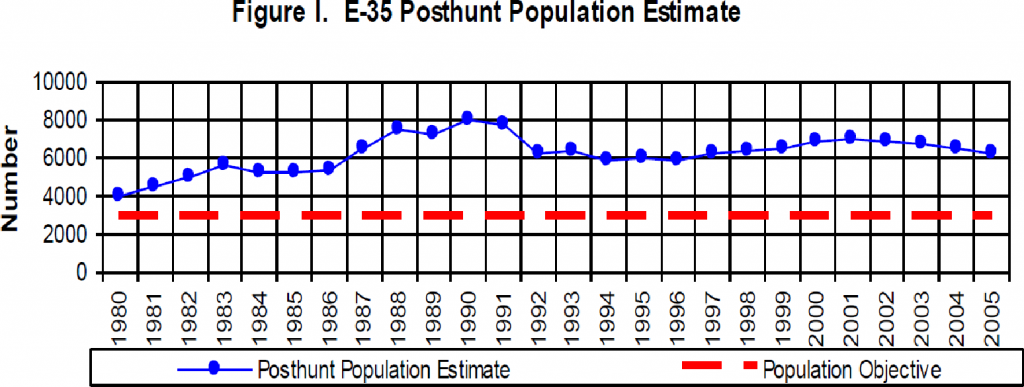

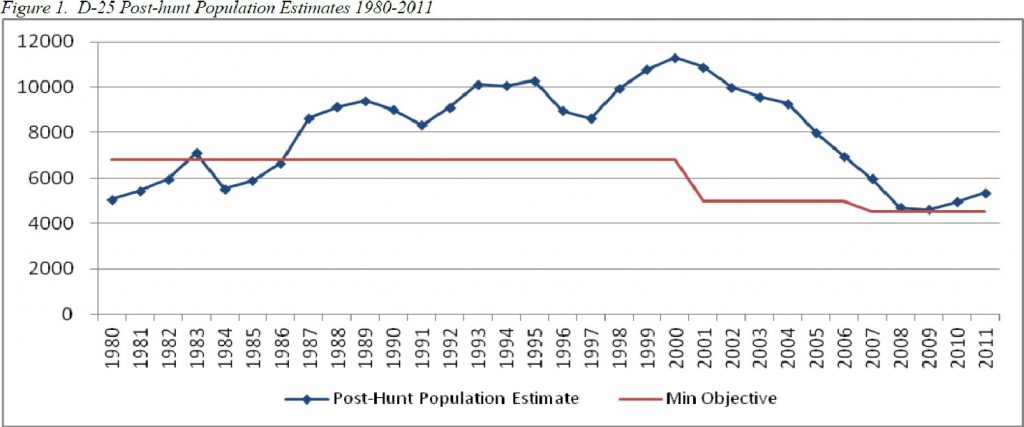

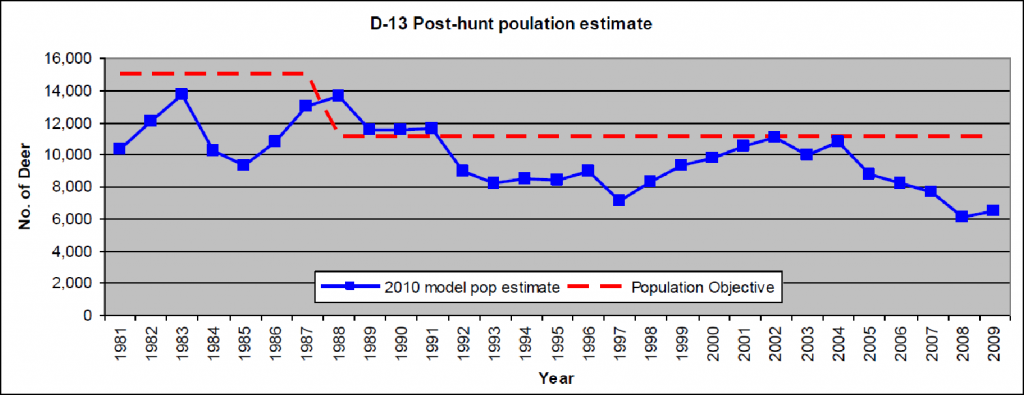

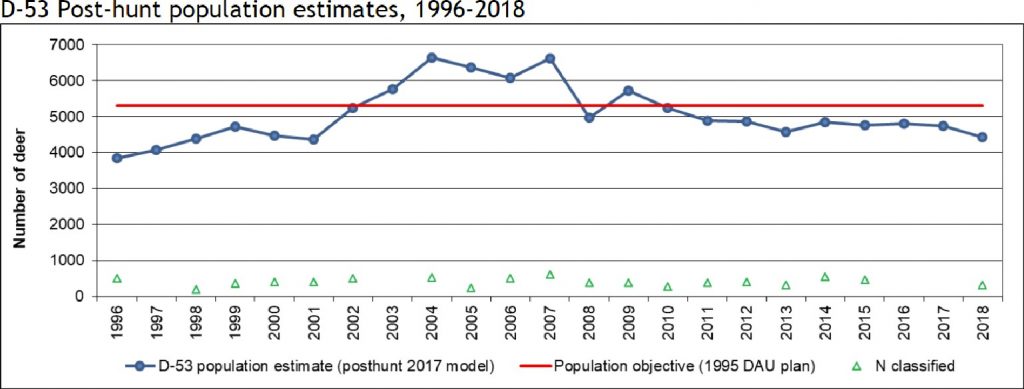

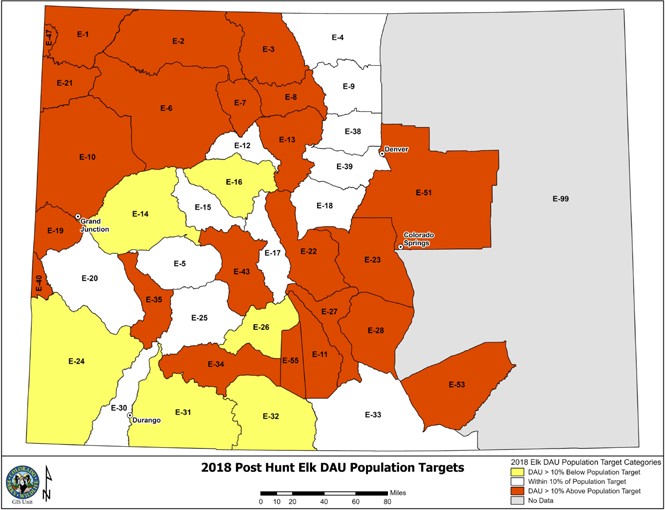

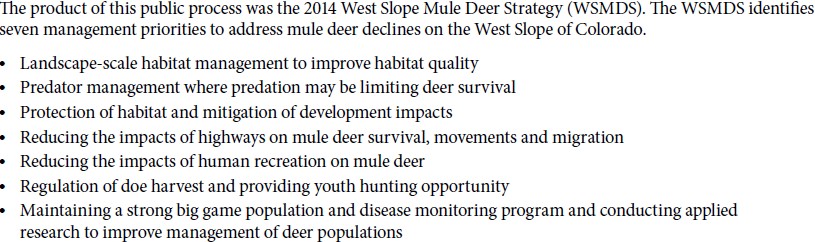

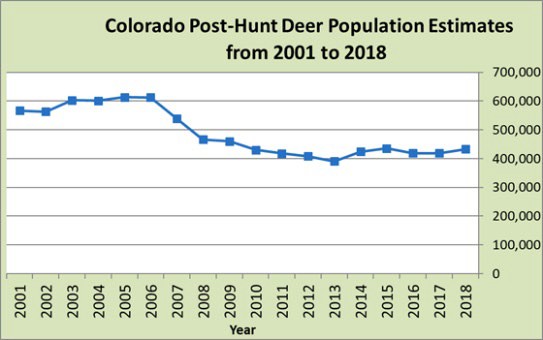

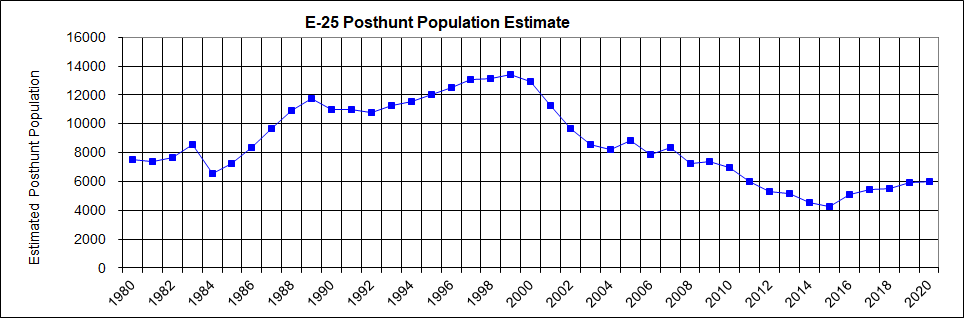

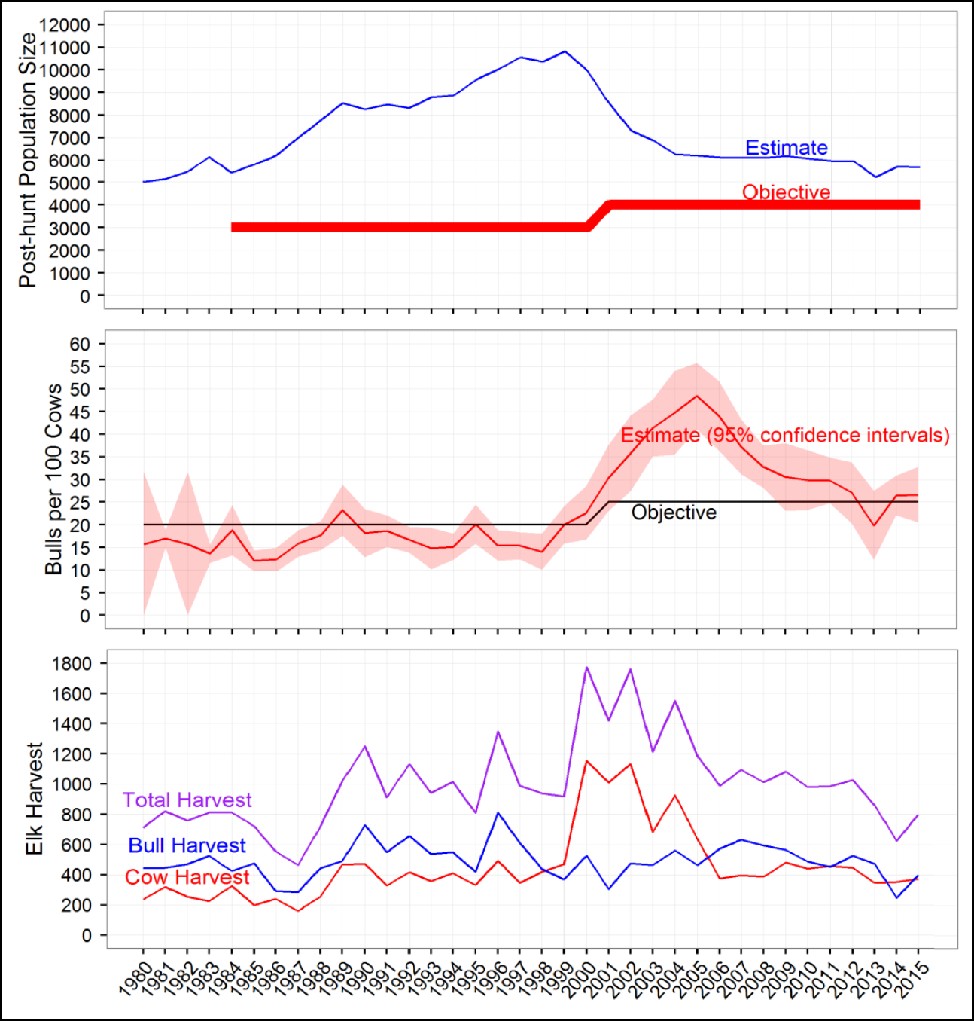

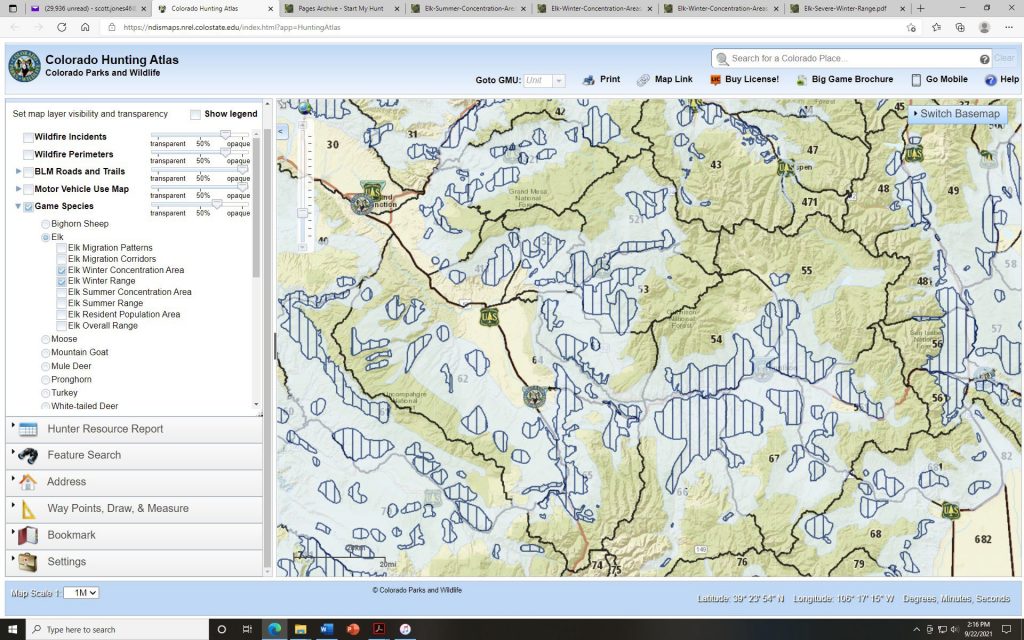

- Populations of wildlife on the GMUG have been steady and increasing over the life of the 1983 RMP, based on published peer reviewed information from CPW and as a result we must question why there would be significant restrictions imposed to protect wildlife beyond those already in place.

- The large-scale implementation of a draconian mile for mile route density standard in wildlife management areas conflicts with USFS and CPW published and peer reviewed guidance on this issue. We are unable to local any species whose habitat is actually entirely under this threshold causing significant concern regarding assertion from the Forest of minimal impacts from this standard;

- Winter ROS information is woefully inadequate and as a result we are asking that any winter ROS decisions be postponed until adequate information is available and can be incorporated in subsequent travel plans for the issues; and

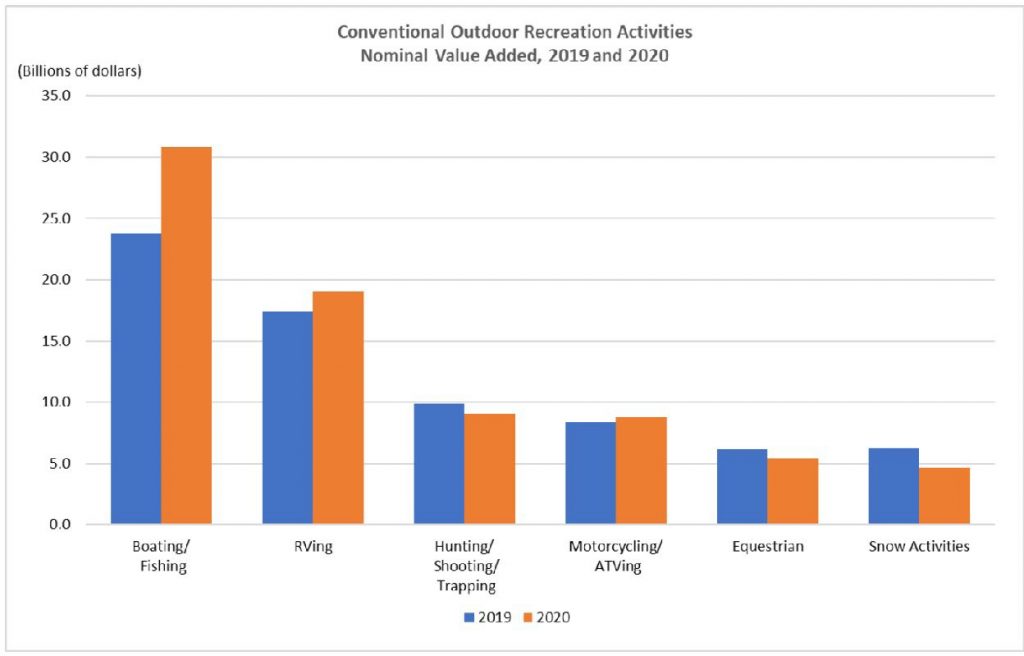

- There simply needs to be more access to the forest for all types of recreational usages, which was confirmed by the complete overrunning of existing facilities in 2020;

Prior to addressing the specific concerns, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 2,500 members seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations. The TPA is an advocacy organization created to be a viable partner to public lands managers, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of motorized trail riding and multiple-use recreation. The TPA acts as an advocate for the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate a fair and equitable percentage of public lands access to diverse multiple-use trail recreational opportunities. CORE is a motorized advocacy and trail work group. They have performed several thousand hours of volunteer work over the past four years in the Gunnison National Forest restoring roads and motorized trails. Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport. Collectively, TPA, CSA, CORE and COHVCO will be referred to as “The Organizations” for purposes of these comments.

The Organizations are very concerned that one of our foundational concerns around the GMUG effort has not been addressed consistently or accurately, and that is developing an accurate reflection of current management on the GMUG. This concern is the fact that site specific NEPA has been undertaken on the GMUG for decades and that this NEPA must be applied accurately and meaningfully on the Forest to represent Alternative A of the Proposal. The development of an accurate Alternative A is foundational to our ability to compare alternatives and to understand where existing expansion areas might be located. An accurate understanding of Alternative A also allows us to avoid unintended consequences of the proposed alternatives on issues that were simply not analyzed accurately under Alternative A of the RMP.

Our concerns around the accurate reflection of current management and collaborative efforts around Wilderness designations began with the high levels of Wilderness recommendations in some discussions. This is an issue we are passionate about as we have worked hard over the last 40 years to have areas protected as Wilderness in concert with the specific release of other areas important to our interests by Congress for Non-Wilderness multiple uses. We believe all portions of these legislative efforts are equally worthy of recognition in any planning. We would not even ask to put a motorized trail in a Wilderness area as this is a non-starter of an issue. We believe that requests for recommended Wilderness designations in areas previously released for multiple use should be equally a non-starter from a management perspective. We are thankful this issue has been resolved in early versions of the plan after extensive discussions with GMUG staff on this issue.

Our concerns around accurate inclusion of existing decisions and NEPA continued in 2018 in response to the GMUG proposal to designate the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail for horse and hike use only. This was again conflicting with previous Congressional determinations on the use of the trail. This standard was in direct conflict with Rio Grande NF planning efforts and either forest changes to management standards could have catastrophic impacts to motorized access on both forests. This was in direct conflict with specific provisions of the National Trails System Act and the extensive programmatic level NEPA analysis that had been previously undertaken to ensure consistent management of the CDNST without regard to forest level boundaries and allowed many uses on various segments of the CDNST. We thank GMUG planners for resolving this concern as a result of our pre-NEPA process comments but we feel it is important to recognize this as the first problematic integration and reflection of existing management and NEPA analysis in the GMUG planning effort. The CDNST issue is unfortunately not the last time we have seen this type of failure in the GMUG planning effort.

The application of existing NEPA in the GMUG planning efforts was again raised by motorized interests after several public meetings were held by partner groups, such as the series of workshops held by Western States University entitled “Winter Recreation Citizen Science Public Workshops” in January and February of 2020. The motorized users were astonished to hear assertions such as: “There has never been winter travel management on the GMUG” actually being validated by USFS staff in the meetings despite the entire GMUG having winter travel management in place. Our concerns on issues on proper integration and recognition of previous NEPA efforts was again addressed the importance of existing NEPA decisions with USFS staff and we again thought this issue was resolved. This issue remains of paramount importance to our concerns and appears to be an issue that has again been overlooked in the GMGU process.

After seeing the first draft of the Proposal, Wilderness designations and releases, the CDNST concerns and winter travel appear to be the tip of a much larger issues around accurately applying existing NEPA on the forest. NEPA has been performed on the forest and simply is not accurately reflected in Alternative A, as some conclusions are ignored and other conclusions are applied in manners that directly conflict with the site or issue specific NEPA. Are we glad these issues are resolved properly, that answer is of course yes but the process has been long and slow.

1(a)(1) Better than the Manti

The Organizations participate in the development of forest plans and travel plans throughout the region and this gives us a somewhat unique perspective on unusual issues. One such issue would be the adoption of the pre-NEPA public review concept on both the GMUG and Manti/LaSal NF at roughly the same time. While both forests have chosen to adopt this new principle, the GMUG has proactively used this process to its fullest advantage by taking the public input that was received earlier in the process and attempting to address this round of public input with a revision of the initial draft. The Manti chose to simply release their initial draft twice without revising the initial draft in response to the public input. While this additional comment period is appreciated, providing some type of meaningful feedback on initial comments would have been superior. The GMUG planners should be commended for undertaking this early revision of their proposal between pre-NEPA and commencement of NEPA process as adding additional input on Wilderness and CDNST issues would expand these comments even more. We believe this step will provide a more accurate plan and sends an important message to the public that their input matters.

1(a)(2) Shorter is better.

The Organizations welcome the generalized and shorter nature of the RMP when compared to the former GMUG. Landscape level plans can be very long and detailed and this length has proven to be a significant barrier to public participation in the planning process as most of the public lack the time or resources to review such a large planning document. This causes the public to oppose the plan even when there are very good things for the public in the plan.

These overly complex and detailed plans also shorten the life and value of the plan as the plan simply lacks flexibility to adapt to changes in science or unforeseen challenges at the time of development. When these changes are encountered, the plan is simply irrelevant factually or recommending management that simply makes no sense in addressing on the ground issues. The current forest health situation on the GMUG provides a perfect example of why RMPs must be flexible and avoid overly detailed analysis, mainly that the GMUG is dealing with areas of the forest where tree mortality is easily at or above 90%. The Organizations submit that the current RMP has been a significant barrier to addressing this challenge, as planners in 1983 were simply unable to understand the scope of the challenges that the forest could be facing almost 40 years after the plan was adopted. Again, these types of overdetailed analysis represent a situation that should be avoided in the development of the new GMUG RMP. Shorter is better.

While the Organizations continue to vigorously support the shorter is better concept for the new plan, this desire should not be construed as a desire to avoid accurate analysis of the NEPA on the forest and the existing RMP and supplements. The creation of an accurate summary of current management on the forest in Alternative A is a critically important step for the meaningful analysis of alternatives that are being proposed and this is a process that the USFS planners are uniquely situated to accurately address. Too often in the Proposal development has this responsibility fallen to the public.

The Organizations believe this shorter is better model is also applicable to protecting access. This is why we are asking for a standard to protect existing routes that have been the basis of extensive travel planning be provided a landscape level management standard to protect these routes that may cross areas of inconsistent management. Not only is it difficult to almost impossible for the public to identify every route in this situation, this presumption also ensures that these routes continue to be protected during subsequent revision processes to address uses and boundaries in response to the current public input.

1(a)(3) We simply need better and more access for all forms of recreation and management.

Another landscape level concern for the RMP would be the desire of the Organizations to clearly and vigorously state that access to the GMUG needs to be improved and expanded when compared to Alternative C. There are simply too many barriers to access to the forest for both recreation and management of the forest moving forward. The organizations are concerned that often portions of existing NEPA reviewed trails are provided more protection under Alternative B than Alternative C. This is perplexing at best and must be corrected.

We believe this access is critical to the continued ability of the forest to provide high quality recreational access to all but also to dealing with the catastrophic wildfires that have become so commonplace. Fighting fires is difficult enough but having to try and build or reopen routes that are only administratively open while fighting a fire makes the firefighting functionally impossible. These concerns are discussed more subsequently but the need is clearly evident from the overwhelming use of recreational resources that occurred in 2020. The GMUG also needs to learn from the firefighting efforts on other forests in response to the monster fires that have now become far too common. From our perspective bringing in a hot shot crew from outside the region and then having a crew like this open trails and routes for basic access is a tragically inefficient use of that crews’ skills and the exceptionally limited funding that is available. If access is maintained more consistently, poor allocations of resources are avoided in times of crisis and the Organizations have provided almost $1 million per year to the GMUG for a long time to provide this type of maintenance, making this management direction a double win.

1(b) The motorized community has a long history of effectively collaborating with everyone to resolve challenges on the GMUG.

The Organizations would like to discuss a foundational difference between the way the motorized community collaborates when compared to other interests. The Organizations and our membership have a long history of collaborating with land managers to address a wide range of issues and challenges on the GMUG and vetting these conclusions through the NEPA process. The Organizations have embraced this type of collaboration in the hope that issues can be permanently resolved and managers and users can enjoy the recreational opportunities on the GMUG now and into the future. Candidly, it can be very tiring for our members to talk about the same areas and issues over and over and over again.

Often, many that have collaborated around NEPA efforts have consistently sought to reopen collaborative decisions made with the USFS within a short time of their conclusion, often asserting positions that are directly in conflict with the scope of the NEPA. Often the basis for the desire to reopen NEPA is basically the same concern that initially drove NEPA analysis and that other parties in the effort thought were resolved. Too often we have had to remind everyone about these collaborations scope and NEPA basis before entering any further discussions, and our desire is to address issues or concerns as much as possible and move on. This often is asserted as obstructionist behavior by those that want to continue discussions. We vigorously assert that this type of closure is the implementation of the collaborative process. The Proposal appears to be another effort that the motorized community will have to serve as the forest historian to allow analysis to commence from an accurate and meaningful management position. Many of the issues that would be reopened in the Proposal over its life we view as issues that have been resolved in previous collaborations around NEPA. The Organizations and our members are hesitant to reopen many of these decisions as the previous NEPA was painful and resulted in large scale restrictions in some areas.

Another significant difference in our collaborations and NEPA implementation is the fact we bring funding to implement decisions to the table. The motorized community has worked hard with the USFS, CPW and BLM to provide funding to address actual on the ground issues and currently this has resulted in a grant program for motorized recreation that provides almost $8 million per year in direct funding to land managers to benefit everyone across the state. As we have previously outlined in our comments, this results in almost $1 million per year coming to the GMUG for funding of staff, crews and site-specific projects. Motorized collaboratives have been hugely successful on addressing on the ground issues and challenges for the benefit of everyone on the GMUG and have become so effective in addressing issues that they are easily overlooked. This model of partnership with the forest is starkly different from most other collaboratives, who often create lists of demands and goals for the forest but provide little to no funding to implement these goals. With this section of our comments the Organizations are highlighting these partnerships to ensure they are properly weighted and recognized in the planning process.

2b. USFS partnerships reports could provide high quality information on partner resources.

With the passage of the National Forest System Trails Stewardship Act in 2016, Congress mandated the creation of a volunteer strategy report to improve partnerships between land managers and user groups for the benefit of trails on federal public lands. While this report is not to be published until 2018, this report should be highly relevant in addressing budgetary shortfalls and identifying partners where resources are more limited and partners where resources are more available as the report requires:

” (b) REQUIRED ELEMENTS. —The strategy required by subsection (a) shall—

- augment and support the capabilities of Federal employees to carry out or contribute to trail maintenance;

- provide meaningful opportunities for volunteers and partners to carry out trail maintenance in each region of the Forest Service;

- address the barriers to increased volunteerism and partnerships in trail maintenance identified by volunteers, partners, and others;

- prioritize increased volunteerism and partnerships in trail maintenance in those regions with the most severe trail maintenance needs, and where trail maintenance backlogs are jeopardizing access to National Forest lands; and”

The largest single partner with both the BLM and USFS in Colorado is the motorized trail user community, both in terms of direct funding to land managers through the CPW Trails Program and with direct funding and resources from clubs in the GMUG planning area. The partnership’s impact is further expanded by the fact that all motorized routes on the GMUG are available for all other recreational activities. The major barrier to partnerships is closures of routes when resources are available to address the resource concerns that are the basis of the route closure and the failure to treat all recreational user groups in a similar manner.

The identification of partner resources available to GMUG managers must be a major priority in the development of the RMP as well. While there are many partner groups who volunteer time and resources in partnership with GMUG managers, the OHV community is the only partner that provides direct and consistent funds to GMUG managers through the CPW OHV grant program to assist in achieving sustainable recreational opportunities. The USFS Regional office has clearly identified that just the OHV program in Colorado more than doubles the amount of agency funding that is available for recreational activity on USFS public lands. After a review of the CPW Statewide Good Management Crew program based in the Sulphur Ranger District of the Arapahoe/Roosevelt NF managers clearly identified that CPW OHV good management crews were provided money in a more consistent and timely manner than the funding that was provided through USFS budgeting and over time the CPW program funding had significantly increased while USFS budgets had significantly declined. There is simply no basis for a decision that this long-term reduction in funding will change and this should be factored into planning for projects on the ground.

In 2017, GMUG managers asked for almost $600,000 in direct funding for annual summer maintenance crews and for site specific projects from the CPW OHV program alone. This funding provides three trained seasonal crews who perform on the ground trail maintenance, provide basic maintenance services for more developed sites and expand the law enforcement presence on the GMUG. Additionally, these crews are able to leverage a significant amount of mechanized equipment in the GMUG planning area, such as the several Sutter trail dozers, mini-excavators and tractors owned by local clubs to address larger maintenance challenges in a very cost- effective manner. We have attached the Ouray RD good management crew grant application to the CPW OHV program (#6) and OHV dozer (#5) application as exhibits with these comments in order to provide clear documentation of the support coming from the CPW OHV program to GMUG managers and the success of these partnerships in maintaining trails.

The availability of these resources exemplifies the strong relationship that the GMUG resource managers have with some of the strongest partner clubs in Colorado, and probably the Nation including the Thunder Mountain Wheelers, West Slope ATV, Grant Mesa Jeep Club, Western Colorado Riding Enthusiasts (WESTCORE) and Uncompahgre Valley Trail Riders. These clubs routinely work on projects, such as bridge construction and heavy trail maintenance, that are simply beyond the scope of comprehension on most other forests. These clubs also provide extensive additional funding for resource maintenance such as grants obtained from the Extreme Terrain Grant Program, BF Goodrich Tires Exceptional Trails and Yamaha Access grant program and Polaris TRAILS grants. This funding easily exceeds another $100,000 per year in funding that is available to maintain routes on the GMUG and other public lands in the vicinity.

In addition to the OHV grant funding and exceptional partnerships available through summer use clubs, CPW funding through the Snowmobile Registration Program provides an additional $500,000 in funding to local clubs for operation of the grooming programs, who maintain almost 400 miles of multiple use winter trails on the GMUG. The snowmobile registration program further partners with the local clubs to purchase grooming equipment used on these routes, which now is consistently exceeding $200,000 to purchase used. This CPW funding is again leveraged with exceptional amounts of volunteer and community support for these grooming programs from local clubs and oftentimes the CPW funding is less than half the operational budget for the clubs maintaining these routes. These winter trails are the major access network for all users of GMUG winter backcountry for recreation and all these opportunities are provided to the general public free of charge.

While there has been a significant decline in direct funding through the agency budget process, motorized partners on the GMUG have been able to marshal resources at levels that are unheard of in other forests for the benefit of all recreational users. The Organizations would ask that if budget constraints are identified as a challenge for recreational usage of the forest moving forward, that these constraints are applied to all recreational usages and that the fact that the GMUG has been the beneficiary of some of the strongest partnerships with the motorized community in the country for literally decades be properly balanced in addressing any budget shortfalls.

In addition to the collaborative management resources that have been available for the benefit of all users of the GMUG, the motorized community has worked hard to address all types of conflict and challenge around recreational usage on the GMUG. As we have outlined in previous comments, these collaborations have facilitated the passage of Wilderness legislation that created Wilderness areas and also released other areas back to multiple use. The Organizations submit these efforts stand in stark contrast to the single minded exclusionary and often inflammatory collaboratives that now seem commonplace around the GMUG planning efforts.

2(a). Existing NEPA and management is not reflected in Alternative A.

The Organizations are very concerned that Alternative A of the Proposal often fails to address site specific NEPA that has been undertaken and/or seeks to apply these decisions in manners that are specifically outside the scope of the NEPA analysis. While the Organizations appreciate the GMUG efforts to resolve these concerns during the public comment period these efforts were late in the comment period and created a significant amount of confusion with our members who were often approaching us asking: “What should we comment on now? The Original or the new information?” Our answer to this type of question has been both and we are adopting the same policy here.

Rather than address existing management designations that have not been altered over the life of the plan, the original version of Alternative A of the Proposal appears to base analysis on inventories of characteristics that are often highly subjective and arbitrary. Additionally, these inventories have been done without NEPA rather than current management designations that are exhaustively reviewed in the NEPA process for the 1983 plan. Often other foundational decisions of these site-specific analysis are not discussed as far more restrictive standards for the issue are simply asserted to be best available science. An example of these types of concerns would be:

- The consistent assertion that only 40% of the GMUG has an ROS inventory in place;

- Management area designations have reduced by 24% over the life of the 1983 plan based on subsequent NEPA when these site-specific decisions clearly and unequivocally state there was no change to management standards is within the scope of that analysis;

- Roadless inventory of limited area characteristics are now sought to be applied as a management standard;

- The complete lack of analysis of existing route density decisions in ESA habitats and critical watersheds on the

Each of these concerns will be addressed with much higher levels of details in subsequent portions of these comments, but the Organizations believe the common ground of all these concerns provides a starting point for analysis. It is well established that NEPA regulations require an EIS to provide all information under the following standards:

“… It shall provide full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts and shall inform decision makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives which would avoid or minimize adverse impacts or enhance the quality of the human environment Statements shall be concise, clear, and to the point, and shall be supported by evidence that the agency has made the necessary environmental analyses “1

NEPA regulations provide as follows:

“(b) NEPA procedures must ensure that environmental information is available to public officials and citizens before decisions are made and before actions are taken. The information must be of high quality. Accurate scientific analysis, expert agency comments, and public scrutiny are essential to implementing NEPA. “2

The Organizations believe a brief summary of the standards that are applied by Courts reviewing agency NEPA analysis is relevant to this discussion as the courts have consistently directly applied the NEP regulations to EIS review. Relevant court rulings have concluded:

“An EIS serves two functions. First, it ensures that agencies take a hard look at the environmental effects of proposed projects. Second, it ensures that relevant information regarding proposed projects is available to members of the public so that they may play a role in the decision-making process. Robertson, 490 U.S. at 349, 109 S.Ct. at 1845.”3

The Organizations have consistently sought to partner with GMUG planners to comply with the above requirements in the development of site specific NEPA on a wide range of issues and concerns. The Organizations and our members are deeply disappointed at the inaccurate summary of efforts that did not address access or only sought to address limited aspects of recreation that has now been portrayed as significant changes in existing management in Alternative A of the Proposal.

2(b)(1) Alternative C is the only alternative that complies with many landscapes level Congressional decisions about land use on the GMUG.

As the Organizations have noted throughout these comments, we have consistently come to the table to work out a wide range of issues that have been encountered on the GMUG. This collaboration has addressed both NEPA driven efforts on the Forest and citizen driven efforts that impact the management of the GMUG. The Organizations assert that Alternative C is the only alternative that reflects the consensus and collaboration that has been reached outside the NEPA process on political questions such as Wilderness designations and releases. Communities have collaborated and moved almost all recommended Wilderness in the 1983 plan to Congressionally designated Wilderness. Communities have also worked hard to gain Congressional release of areas from future designations and Alternative C reflects these Congressional releases and the Organizations believe this is crucially important moving forward. The Organizations discussed these designations and decisions in great detail in the comments submitted by the Organizations in response to the Wilderness Assessment of the GMUG on May 31, 2018 and remain a major concern for the Organizations. 4

2(b)(2). EO 14008 issued on January 27, 2021 by President Joe Biden mandates improved recreational access to public lands.

The Organizations are aware there has been an increase in public concern on issues that are truly a success on the GMUG or are based on partial summaries of large-scale actions that have been taken by the President or Governor. The recent issuance of Executive Order # 14008 by President Biden on January 27, 2021 would be an example of a decision that is only partially summarized in most materials we are seeing, as the 30 by 30 concept is memorialized in this order. It is our position that the 30 by 30 concept was long ago satisfied on the GMUG as 50% of the GMUG is either Congressionally designated Wilderness or Roadless area. In direct contrast to the materials we are seeing, this Order had provisions protecting lands generally but also had specific goals of improving access to public lands.

The only Alternative that complies with these specific recreational access goals of improving access is Alternative C. §214 of EO 14008 clearly mandates improved recreational access to public lands through management as follows:

“It is the policy of my Administration to put a new generation of Americans to work conserving our public lands and waters. The Federal Government must protect America’s natural treasures, increase reforestation, improve access to recreation, and increase resilience to wildfires and storms, while creating well- paying union jobs for more Americans, including more opportunities for women and people of color in occupations where they are underrepresented.”

The clear and concise mandate of the EO to improve recreational access to public lands is again repeated in §215 of the EO as follows:

“The initiative shall aim to conserve and restore public lands and waters, bolster community resilience, increase reforestation, increase carbon sequestration in the agricultural sector, protect biodiversity, improve access to recreation, and address the changing climate.”

217 of EO 14008 also clearly requires improvement of economic contributions from recreation on public lands as follows:

“Plugging leaks in oil and gas wells and reclaiming abandoned mine land can create well-paying union jobs in coal, oil, and gas communities while restoring natural assets, revitalizing recreation economies, and curbing methane emissions.”

The Organizations are aware of significant concern raised around the 30 by 30 concept that was also memorialized in EO 14008. While the EO does not define what “protected” means, the EO also provides clear and extensive guidance on other values to be balanced with. From our perspective the fact that the GMUG is currently managed as 30% roadless and almost 20% Congressionally designated Wilderness far exceeds any goals for the EO. From our perspective, the only alternative that complies with EO 14008 is Alternative C as the GMUG has exceeded the 30% threshold and also must improve recreational access. Improving access and revitalizing recreation economies simply will not happen with significantly expanding restrictions on access such as the 27% increase in areas generally closed to the public as proposed in Alternative D of the Proposal. While Alternative C of the Proposal starts to satisfy these requirements, this Alternative does not go far enough as we believe many of the foundational assumptions around Alternative C have been heavily influenced by faulty information that has been provided to USFS staff from other partners.

2(b)(3) The Goals of the Congressionally mandated USFS National Trails Strategy only aligns with Alternative C of the Proposal.

The USFS has been developing the National Sustainable Trails Strategy for the last several years5, to comply with the mandate of the National Trails Stewardship Act of 2016.6 The National Trails Strategy has a clearly identified goal of improving sustainable access and partnerships as a goal of this Congressionally mandated effort. This strategy also sought to strategically change how the USFS looks at partners and sustainability of routes and given the Proposal will guide the sustainable access and partnerships on the Forest for the foreseeable future. The Organizations are commenting on this issue given the fact this effort is simply never mentioned in the Proposal, despite the Congressional mandate. The National Strategy clearly states this as follows:

“Strategic Intent

The strategic intent of the strategy is to embrace and inspire a different way of thinking—and doing—to create sustainable change where grassroots initiative meets leader intent. The combined effort and momentum of many minds and hands will move the trails community, as a whole, toward shared solutions. This strategy builds on the many examples from across the country where the Forest Service, its partners, and the greater trails community have successfully embraced a community-driven and locally sustainable trail system model.”7

As we have noted throughout these comments the motorized community has worked hard to develop community driven locally sustainable trail systems on the GMUG for decades. While the motorized community is far from perfect, the motorized community is the only community that brings significant resources to the GMUG to assist with management and maintenance of routes for the benefit of all users. The CPW OHV program is probably the largest trail partner with the GMUG and this program is predominantly funded from the voluntarily created OHV registration program. This significant direct funding probably makes the motorized trail network the most sustainable on the GMUG. These contributions were recently recognized by the USFS planners as part of the sustainable trails effort as follows:

“The engagement and efforts of motorized groups have improved the condition of trails across National Forest System lands and we look forward to continued engagement with the motorized community as part of the Trail Challenge…. During phase one, I welcome collaboration to adequately track, monitor, and acknowledge accomplishments by the motorized community while identifying lessons learned to incorporate into future phases of the Trail Challenge.”8

While many interests are struggling mightily to provide a single maintenance crew, the motorized community has provided more than 60 well equipped and trained crews throughout the state for decades. We believe this is a model of collaboration moving forward and the Proposal should avoid any unintended negative impacts to this collaboration.

In addition to the direct funding of USFS management, the sustainability of the motorized community is significantly buttressed by the fact that every route available for usage by the motorized community has been subjected to 50 years of scrutiny under the travel management Executive Orders issued by President Nixon in 1972. While these 50 years have often been challenging for everyone, it has also produced the most analyzed and sustainable trail network for any usage. No other recreational activity on the Forest has been subjected to this level of scrutiny and analysis. The Organizations believe the strategic implications of choosing an alternative that restricts or maintains access to the forest fails to provide that carrot to the users who have worked so hard to date to create a sustainable trails network that aligns with the national efforts. The value of this type of message should not be overlooked, as such a decision would provide a significant message that the USFS is actually changing how they view and achieve sustainability with partners. This type of a strategic carrot is only provided in Alternative C of the Proposal but even this carrot is small and should be looked at for expansion to ensure access is actually improved. The Organizations would note that every other Alternative conflict with the requirements of the National Trails Strategy.

2(b)(4). The USFS Regional trails strategy requirements of maintaining, increasing or enhancing access is only supported by Alternative C.

Region 2 of the USFS has also chosen to address the Sustainable trails challenge by developing a similar regional strategy. The Organizations have been active participants in the development of a Regional Sustainable Trails strategy development, which is a parallel effort with the National Sustainable Trails Strategy development. The Goals and Objectives of the Regional Trails Strategy directly and clearly require increased access to public lands as follows:

“Goal 1. Access to high quality recreational settings and opportunities is maintained, increased and/or enhanced.

Goal 2. Equitable, diverse, and inclusive trail programs are encouraged and supported.”

A complete copy of this strategy is attached to these comments as Exhibit “B”. Again, the regional strategy provides clear and unequivocal guidance that trail opportunities are expanded. The Organizations also assert that Alternative C is the only alternative that provides opportunities to increase or enhance recreational settings currently and more importantly over the life of the plan. The enhancement of recreational opportunities on the GMUG will only occur with Alternative C as given the significant population growth of the GMUG planning area, simply holding levels of access will degrade access as visitation will continue to increase. The Organizations would note that every other Alternative conflict with the requirements of the Regional Trails Strategy.

2(c). Why the Organizations are vigorously opposed to Alternative D

The Organizations would note that the vigorous opposition to Alternative D is based on the catastrophic impacts it would have on multiple uses, which the DEIS summarizes as follows:

“Within alternatives B and C, the target would be to complete five actions per decade to meet this objective. Within alternative D, that number would increase four-fold to 20, representing a much more expansive and active management approach to maintaining semi-primitive settings.”9

By comparison, only 1% of the GMUG is managed for recreational emphasis. 10 To say this impact is totally unacceptable to the motorized community and in no way represents visitation to the forest would be an understatement.

Under Alternative D, 77% of the forest would be restricted either as Wilderness or Roadless which would directly conflict with Presidential Executive Orders and National and Regional strategies that are mandated by Congress. This again is totally unacceptable to the Organizations and directly conflicts with the clear mandate of President Biden’s EO 14008 to improve recreational access. Alt D directly conflicts with Goal #2 of the Regional Sustainable Trails initiative given the huge amount of special management areas that are only for the benefit of a single interest group and its failure to improve recreational access to public lands.

It is significant to note that collaboration from the motorized community excludes no other user group, and candidly we are the only user group that can start a discussion with this point. Every other user group advocates for their interest only and seeks to exclude everyone else. As the Organizations have outlined throughout these comments, the motorized community has worked hard to collaborate on a wide range of issues on the GMUG over the life of the 1983 RMP. Many of the community-based proposals that are reflected in Alternative D are a summary of the portions of previous proposals that only benefitted a single user group that we agreed would not be applied in previous collaborations. Our opposition to Alternative D is a request that these previous collaborations be honored moving forward on the forest.

3a. Erosion of opportunities on the GMUG asserted to have occurred without NEPA precludes meaningful commenting on the range of alternatives.

The Organizations are concerned with the serious foundational issues with Alternative A (current management) of the draft RMP. Our concerns center around two general issues that are critical to our ability to understand and comment on the Proposal as functionally we have no basis of management for comparison. The Organizations are very concerned that these are two more examples of the planning effort simply failing to accurately reflect current management on the GMUG.

The Organizations are aware that some of the concepts and standards in the 1983 RMP are simply out of date or don’t align well with current management and this can be somewhat difficult to align and portray. At the least there needs to be significant clarity added to Alternative A of the proposal to allow for meaningful discussion of management allocations, rather than ROS inventories, as these management allocations are the heart of the RMP and EIS process. The foundational issue critical to a meaningful NEPA process and public engagement is “What is current management on the GMUG?” The issue is so systemic and pervasive as to cause the Organization’s great concern around the basic analysis of impacts from changes, as we have no baseline to compare too. There is so little information provided around how decisions were made to alter current management on 24% of the forest. The Proposal proceeds under the guise that the 24% reduction in motorized access is current management and as a result we simply are unable to meaningfully address lost opportunities on 24% of the forest. The impact this has on the public ability to comment and participate in the process based on the limited and incorrect information provided, Alternative B appears a viable option due to its minimal changes to current management. Our concern is there is an understatement of access provided by current management by as much as 24%, making impacts of even minimal closures to access far more severe on the ground and largely unanalyzed.

We are concerned that at many locations in the draft the concept of the Recreational Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) is portrayed as a management tool rather than an inventory tool to support management. We are intimately familiar with the ROS concept and have supported its use in the past for a wide range of challenges, but we are also very concerned that often ROS fails to convey the actual management designations in areas. ROS, used at the landscape is at best highly subjective in interpretation as it relies on generalized standards on the forest, such as xx ft from a road moves to a lower ROS designation and these designations move further towards primitive at set distances from the road. This often bears absolutely no relationship to the topography of an area, volume of usage on the road or the fact that the road can alter its usage over the course of a single year. For the Organizations, the management designations can provide a huge amount of flexibility in the management of recreational opportunities and this flexibility is simply not conveyed in any manner by the mere presentation of ROS information.

3(b). Significant suitability and management area decisions have been made without NEPA and cannot be corrected with mere wording changes.

The Organizations are aware the GMUG has had a long and complex planning history. The Organizations are also aware that the concerns raised in this portion of our comments have been addressed at some level with amendments to resources created for public meetings. While we welcome these new resources and analysis, this step was very late in the process and only resulted from extensive discussions and effort from the Organizations and partners. While this new information was well received it also created significant confusion among our members as this was a significant change to assertions previously made. People were simply not able to understand what to comment on, the proposal as written or the information now being provided in public meetings.

The Organizations are vigorously opposed to the positions that were taken in public meetings that this was a situation which could be corrected with wording changes. An alteration of 60% of the foundational ROS on the forest is simply not a wording issue. These management areas and utilization levels are important resources for the motorized community and are important to the comparisons of alternatives and public access. The GMUG was one of the first forests in the country to comply with the travel management mandates of President Nixon’s EO 11644. Many subsequent travel management plans on the forest have taken decades to develop and complete NEPA review of. The Organizations are aware that some of the decisions have been undertaken without the NEPA process but rather have occurred through Congressional designations and protections of usages. Congressional actions have impacted a comparatively small portion of the GMUG.

While there are reasons that ROS and existing management decisions could be legally changed on a local level on any forest, none of these reasons and analysis are discussed in the Proposal on even a site-specific basis. Rather the Proposal provides that a 24% change in management has occurred simply due to erosion of the NEPA based decisions made in the 1983 RMP and subsequently. The significant impacts to multiple use access from this erosion is outlined in table 146 of the DEIS as follows:

| Summer ROS – Existing

inventory |

Primitive | Semi Primitive Non-motorized | Semi Primitive Motorized | Roaded Natural | Rural |

| 1991 GMUG

Supplement (1983 allocation) |

217,900 | 816,800 | 1,265,200 | 619,200 | 33,000 |

| Current

management |

435,000 | 1,338,400 | 767,800 | 415,300 | 9,000 |

| Change as % of

forest acreage |

+7% | +18% | -18% | -7% | -.8% |

| % Change to

Original |

+100% | +64% | -39% | -33% | -73% |

The 1983 RMP clearly identifies that 64% of forest was motorized open in some capacity to motorized usage when the detailed EIS for development of the 1983 RMP is reviewed. The Proposal simply asserts that this has changed due to the 1991 GMUG RMP supplement and we must assume we are supposed to accept this access and NEPA has simply eroded to 40% of the forest without detailed explanation. This assertion is impossible to accept at any time and represents a management model that would simply render the entire NEPA process void if allowed to move forward. This is the type of management model that the NEPA process was put in place to avoid.

Not only is this position legally insufficient, the factual basis is severely lacking as well. Three general assertions are made for this management change, covering 5 pages of the EIS, and the reasoning for these changes is simply incorrect and offensive to the partnerships that the motorized community has worked hard to establish on the GMUG. The first reason for this 24% reduction in access is due to mapping, which is specifically addressed as follows:

“One difference is simply that the modeling techniques used were completely different, and the newer models use three-dimensional topography and different buffering techniques, so comparison is simply not one-to-one. Old, locatable maps from the 1991 inventory are sheets of mylar that were estimated with a wheel but never incorporated into the corporate data systems of new.”11

This assertion is offensive to the basic reality of levels of utilization of existing management designations, the Organizations are not going to dignify it with a substantive response. 24% of the GMUG management area designations have been changed and that is simply not a mapping error. Management designations are management designations and inventories are inventories and these classes of information should not be overlapped as they are factually and legally different.

The second reason is also inaccurate and flies in the face of basic NEPA processes as it asserts the 1991 Timber Supplement to the RMP granted unfettered access to managers to amend the RMP in any manner they found necessary. This explanation is a prime example of how the ROS inventory is portrayed as a management decision rather than an inventory tool. The Proposal summarizes this reason as follows:

“Beyond mapping techniques, however, much of the shift in acreages between inventories can be explained because the 1991 forest plan contains a lack of management direction to maintain desired summer recreation opportunity spectrum classes on the majority of the GMUG. Rather than plan direction shaping allocations as they have formed over the life of the plan, project-level decisions such as travel management analyses have shifted recreation opportunity spectrum allocations in the absence of any firm guidance.”12

This analysis is again a comical misrepresentation of the limited scope of 1991 RMP Timber Supplement, which is clearly stated in the 1991 Supplemental Amendment of RMP as follows:

“The enclosed Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (FSEIS) and the accompanying significant amendment deal with timber management Issues. Changes in management of other resources such as recreation or wildlife are not proposed.”13

The anticipated impacts on existing ROS decisions for recreational access are specifically addressed in the 1991 Timber Supplement as follows:

“Each management activity, specifically timber management and road construction projects, would be planned and designed to meet the physical setting criteria for each Recreation Opportunity Spectrum Class and its associated Visual Quality Objectives. Each management activity would conform to the Standards and Guidelines.”14

Given that the 1991 Timber Supplement specifically states that planners are not changing any recreational access, any assertion that the Timber Supplement allowed wholesale changes without NEPA analysis lacks any basis in fact or reality. Planners clearly provide the affirmative statement that recreational decisions will continue to be governed by existing ROS requirements and existing management decisions and designations. Given these clear and unequivocal statements about access, existing management and ROS decisions, the Organizations cannot envision any actual basis for changing the allocations of recreational opportunities from the 1983 requirements. The 1991 Supplemental clearly states 1983 management decisions and ROS requirements are carried forward unchanged for recreation. The 1983 RMP ROS allocation of the GMUG are clearly provided as follows15:

We agree with the Proposal that at any point any land manager could alter a forest plan or travel plan in any way, but we must disagree that the 1993 Timber Supplement created this ability. The wide range of planning regulations have provided this authority for decades such as the National Forest Management Act. The NEPA process specifically requires a detailed statement of high- quality information on this decision-making process must be provided. Merely recognizing statutory authority is not compliance with NEPA.

The third reason provided for the 24% reduction in access between 1991 and the current time is such a completely twisted interpretation of the Travel Management process that again we are dumbfounded. This reason is summarized as follows:

“Additionally, major policy changes occurred with the 2005 Travel Management Rule, which forced the agency to look at site-specific, motorized routes and whether they were a part of the GMUG’s desired network of sustainable routes. When the 1991 forest plan was written, the Forest Service still allowed activities like cross-country travel, but after the 2005 Travel Management Rule was in effect, the agency eliminated many motorized routes and areas from public use. Certain areas were closed that were once open to cross-country travel, administrative routes such as timber roads that were once open to the public were gated, certain trails were converted to non-motorized trails, and if a route was unsustainable, such as an eroding trail traveling straight up a fall line or a user- created trail through a riparian zone, it was closed. All of these actions were compliant with forest plan direction, regulations, and policy; however, when those locations are modeled contemporaneously, the result is a shift from roaded natural and semi-primitive motorized to semi-primitive non-motorized on the recreation opportunity spectrum in the newer inventories.”16

Again, this is an example of the failure of planners to accurately summarize the GMUG planning or the National Travel Management Rule. The GMUG was one of the first forests in the country to adopt some type of travel management. The Organizations have submitted travel maps from 1993 that clearly identify that the GMUG was managed under a landscape model of open, restricted or closed at that time. Rather than being the major policy change that the planners are asserting, the 2005 Travel Management Rule clearly states that existing travel management decisions should be treated as follows:

“Nothing in this final rule requires reconsideration of any previous administrative decisions that allow, restrict, or prohibit motor vehicle use on NFS roads and NFS trails or in areas on NFS lands and that were made under other authorities, including decisions made in land management plans and travel plans. The final rule adds a new paragraph (b) to §212.50 to clarify that these decisions may be incorporated into designations made pursuant to this final rule.17

Given that the 2005 Travel Rule specifically states existing decisions can come forward without revision, and there has not been any travel plans updated outside the Gunnison Basin plan in 2012, we must question why there was thought to be any impact on the decisions predating the 2005 Rule. Restricted to designated routes did not change as a management category and Wilderness areas still remained closed.

This summary of the Travel Management Rule is such a completely twisted summary of the Travel Management Rule it is astonishing as at no point have any of the travel plans created on the GMUG been presented in combination with an RMP amendment. Not only would the automatic alteration of RMP management designations probably be an illegal interpretation of the Travel Management Rule generally, this position utterly ignores the large number of travel planning efforts on the GMUG that have been undertaken and chosen to NOT amend the Forest Plan prior to 2005. The Travel Management Rule and Resource Management planning efforts are entirely separate processes, and we have never heard a summary of these efforts such as that above. Designation of a route NEVER automatically change the management designations of any area. If an area is open to motorized access, it remains open to motorized access pursuant to the RMP qualifications, such as seasonal closures or other restrictions. Decisions such as travel management could also choose to undertake an RMP revision as part of the travel process. Such a decision would simply require more detailed and extensive NEPA analysis for the decision. That analysis has never happened.

Not only is the above statement a comically inaccurate summary of the Travel Management Rule, it is not supported in any manner by large scale travel management efforts that have occurred on the GMUG forest. We are not aware of any combined RMP revision and Travel Plan that addressed significant portions of the forest. Directly to the contrary this type of combined decision making, 2002 GMUG undertook a complete travel management plan for the Uncompahgre Forest. This extensive analysis again clearly stated the travel plan relationship to the existing Resource Management Plan for the forest as follows:

“Restriction on use and management necessary to attain certain ROS Class categories, such as Semi-Primitive Motorized or Semi-Primitive Non-Motorized would essentially impose new Forest Plan level direction, and would be significant in terms of the effects on the Forest Plan. The analysis and decision process that would be required to undertake such a change goes far beyond the scope of this Travel Planning process, and hence I deferred making the ROS decision here. That is better addressed in the upcoming Forest Plan Revision.”18

Similar clear and unequivocal statements of the scope of the 2002 Uncompahgre Travel Planning efforts are printed on each map that was provided to the public at this time. This notice states as follows:

“Recreational opportunity spectrum (ROS) as portrayed on this map represents the ROS which would be the consequences of this alternative, if travel were the only determinant of ROS. ROS is not part of the travel management decision that will be made based on the DEIS.” 19

Given the clear and unequivocal position of the Forest that ROS changes are to be undertaken in the RMP revision process and are outside the scope of the Travel Management Planning process for the Forest, we must question how there has been a massive reallocation of these designations on the GMUG since this time. We are also very concerned that all these changes have been undertaken without NEPA and are now merely being passed off as current management. ROS should not change on portions of the forest that were already closed to motorized or managed as restricted to designated routes.

Similar sentiments regarding the scope of Travel management remaining within existing management were also clearly stated in the 2010 Gunnison Combined TMP as follows:

“This decision is consistent with the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan (1983 as amended in 1991 and 1993). This decision does not require any amendments to that plan in order to implement the designations and produce an MVUM for the Gunnison National Forest”20

Given that these management designation decisions have been made for 24% of the GMUG without NEPA analysis, we vigorously assert these decisions must be analyzed under NEPA and do not reflect current management in any way. The rationale for these decisions is astonishingly incomplete and fails to provide any information for the Organizations or motorized community as a whole could possibly provide a substantive comment on. Management areas are management areas and inventories are merely inventories and these are entirely different processes and decisions and should remain so.

First possible resolution of comment #3 concerns.

The Organizations believe the only manner to meaningfully resolve issue 3 of the comments is to revise the draft RMP to address management designations and accurate information around levels of utilization of these areas and then allow public comment on this document. We believe after management decisions are reviewed, rather than highly subjective inventories, a draft revised plan should be released to the public for comment.

Second possible resolution of comment #3 concerns.

As the Organizations are unable to understand existing management and allocations to understand where trails are consistent with existing management and where they conflict, the Organizations believe there could be another resolution of this issue. Factually there are simply too many routes traversing areas where management may or may not be consistent with the trail location to list with any specificity. If such an inventory of routes was attempted, we are not optimistic the inventory would be accurate at any level and we don’t want to lose routes due to administrative oversights. This protection is comically important to our interests and hundreds of miles of existing routes are moved into areas that are no longer consistent with that usage. We have developed a list of site-specific routes in this situation in the comments subsequently but this is far from complete. Nationally recognized routes such as Black Bear, Imogene and far too many other routes to address in detail in these comments are in this situation and have been analyzed in site specific travel management. We vigorously assert this intent must be reflected in the RMP.

Throughout the presentations we continued to hear from USFS staff that there was no desire to close routes that cross areas of inconsistent management or designation, such as a motorized route that has been permitted in site specific NEPA in areas that are now semi primitive non-motorized. This desire is not stated in any manner in the Proposal and must be clearly and directly clarified at the landscape, as we are not confident in site specific efforts. While there are consistent challenges around ROS and management designations in the RMP, the Organizations are proposing to utilize the fact that every route on the GMUG has been through at least one round of travel management. Many have been through several rounds of travel management, which will allow us to conclude risk to resources from these routes is minimal at best.

As each route has been through travel management multiple times, we are asking that a management standard be created on the GMUG that clearly and directly provides routes with sufficient space to allow the route to exist regardless of ROS designation adjacent to the route. This corridor must be of sufficient size to allow continued use of the route and also provide flexibility for issues such as mapping issues, short distance realignments that might have been undertaken to protect resources in the area and other management flexibility. The Organizations are aware that numerous forests, such as the GMUG have sought to place corridors around trails such as the CDNST and numerous forests, such as the Inyo in California, have placed similar corridors around the PCT. While we have generally opposed these corridors, it is important to understand our opposition to these corridors was not based on the corridor concept but rather came from the fact that the Corridor conflicted with statutory protected usages on the trail and conflicted with existing management. Our request here is very different as we are asking for a corridor that protects legal usages that have been reviewed multiple times from the application of management standards that are unrelated to the trail.

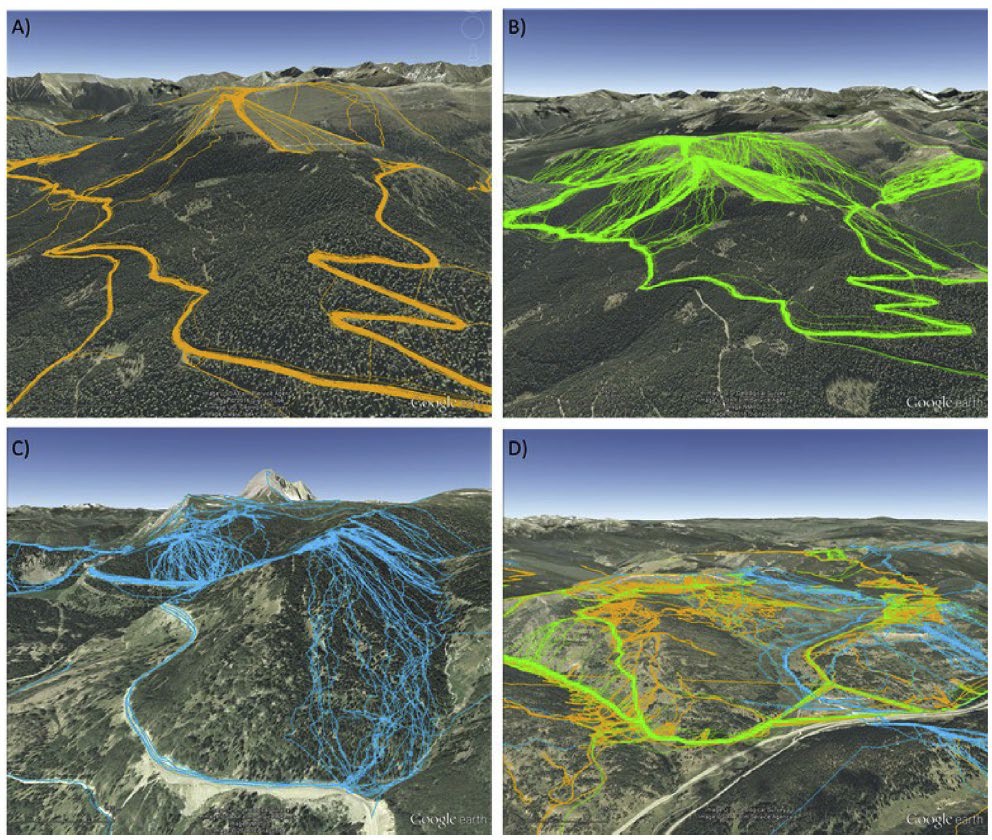

3(c). Winter ROS and usage data is horribly incomplete and decisions on this issue must be postponed until sufficient accurate information can be obtained.

The Organizations are also very concerned that the current ROS data is totally lacking around winter motorized usage as well and we are very concerned this usage has been a major topic of discussion on calls and virtual meetings. Almost as much concern has been raised from the non- motorized community as the motorized community on the inaccuracy of data that is currently available. We believe ROS data is worse for winter usages than summer. Again, we have heard from managers that they do not want to close existing areas and that decisions like that are outside the scope of the Proposal.

While this issue is an important concern for the snowmobile community, we are not confident that most CSA members even understand what the problem is or why it is an issue despite our best efforts. This is a major concern as most commonly our members’ response has been something to the effect that ROS should not matter, we did travel management for the area. Many other members are simply scrambling to get groomers functioning for the upcoming season and are not concerned simply because there has not been a lot of conflict on the GMUG around winter access for a long time. Obtaining and reviewing access data is simply an overwhelming task on a forest the size of the GMUG for just winter recreation and simply cannot be accomplished in the 90-day time frame for a public comment.

Resolution of issue 3c.

Any winter ROS or travel analysis be postponed until winter travel management in that area is updated or undertaken. This will allow far more meaningful engagement of the public on a much smaller geographic scale and generate a far better result. Again, the Organizations are requesting this postponement as the GMUG has already gone through several rounds of winter travel management and we are not aware of major impacts to any resource from winter travel management as it is currently managed.

4(a). The 3.1 management designation of “Colorado Roadless Area” attempts to manage local decisions based a national inventory process of limited factors which simply confuses the public.

The first utterly confounding issue on Roadless Area management is how was the decision made to designate the 3.1 management area in the Proposal as a “Colorado Roadless Area.” If the goal of this decision was to completely confuse and confound the public and preclude meaningful comment on this issue, that goal has been completely achieved. The Organizations must also question why an association of any management area to one of the most litigated concepts ever created in Forest Planning was thought to be a positive. For purposes of our comments, we will refer to the Colorado Rule as the “Colorado Roadless Rule” and the proposed management area designation as the “3.1 Management Designation.” The fact that the public has to start with such basic information and decisions in the hope of making comments understandable to the forest is an indication of serious problems with the Proposal.

Not only is the name one of the worst we have encountered, the Organizations have no idea how you manage an area to an inventory process that only dealt with a limited number of activities in the areas and clearly and repeatedly stated it was not a management designation. The Colorado Roadless Rule provides guidance on management that might impair these characteristics when these areas are identified, such as precluding road construction but allowing trail construction of all kinds if consistent with management decisions for the area. This would only seem to invite litigation of the Proposal rather than avoid challenges.

The 3.1 Management Designation is described in the Proposal as follows:

“Colorado Roadless Areas – MA 3.1 (CRA)

Management within Colorado roadless areas will be consistent with the Colorado Roadless Rule, 36 CFR 294 Subpart D – Colorado Roadless Area Management Desired Conditions

MA-DC-CRA-01: Colorado roadless areas encompass large, relatively undeveloped landscapes characterized by high-quality soil, water, and air that provide drinking water, habitat for diverse plant and animal communities, outstanding backcountry recreational experiences and high-quality scenery, and other roadless area characteristics, as defined at 36 CFR 294.41. Natural processes within the context of the natural range of variation (insects, disease, and fire) occur with minimal human intervention.”21

The direct conflict of this management standard is immediately apparent when the National Roadless Rule scope is reviewed. This scope specifically states why the Roadless Rule exists and the limited scope of any Roadless effort as follows:

“This final rule prohibits road construction, reconstruction, and timber harvest in inventoried roadless areas because they have the greatest likelihood of altering and fragmenting landscapes, resulting in immediate, long-term loss of roadless area values and characteristics. Although other activities may also compromise roadless area values, they resist analysis at the national level and are best reviewed through local land management planning. Additionally, the size of the existing forest road system and attendant budget constraints prevent the agency from managing its road system to the safety and environmental standards to which it was built. Finally, national concern over roadless area management continues to generate controversy, including costly and time-consuming appeals and litigation (FEIS Vol. 1, 1– 16 to 1–17). This final rule addresses these needs in the context of a national rulemaking.”22

The FEIS prepared for the Colorado Roadless Rule clearly states that any Roadless Rule efforts are an inventory of specific characteristics of lands and provides general guidance for the management and protection of these characteristics. It is not a management decision or management designation, which is clearly stated in the Colorado Roadless Rule process as follows:

“Forest plans contain forest-wide direction, as well as direction specific to each allocated management area. Management area direction typically defines management practices and land uses to be emphasized on NFS lands within that management area, as well as the activities that are limited or prohibited within the area.…. The inventoried roadless areas (IRAs) and Colorado roadless areas (CRAs) overlap many different management areas, and management area allocations are variable among the forest plans.”23

The need for subsequent management decision making in any area having Roadless characteristics is clearly stated as follows:

“Decisions concerning the management or status of motorized and non-motorized trails within Colorado Roadless Areas under this subpart shall be made during the applicable forest travel management processes.”24

Roadless areas rules are not a management decision but rather an inventory of the characteristics of these areas. Why that line would ever be blurred is confounding and must be corrected as the current model completely precludes meaningfully comment on any aspect of the CRA rule application or the application of the 3.1 management area designation. In addition to the confusion of the public on this issue, the Organizations must question why alignment with one of the most litigated forest management issues ever was thought to be a positive.

4(c) The Colorado Roadless Rule application is woefully incomplete in the 3.1 Management area.

The Organizations are also very concerned about the application of the Colorado Roadless Rule in this decision-making environment and how this major rulemaking was integrated into the analysis of current management and the range of alternatives provided in the GMUG proposal. The application of the Colorado Roadless Rule was a major concern in our previous comments on Wilderness Inventories and the planning effort more generally. This concern was raised with the GMUG staff in a phone call earlier this month and avoided completely with an assertion that these Roadless area decisions were put in the right category.

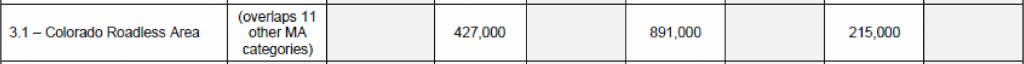

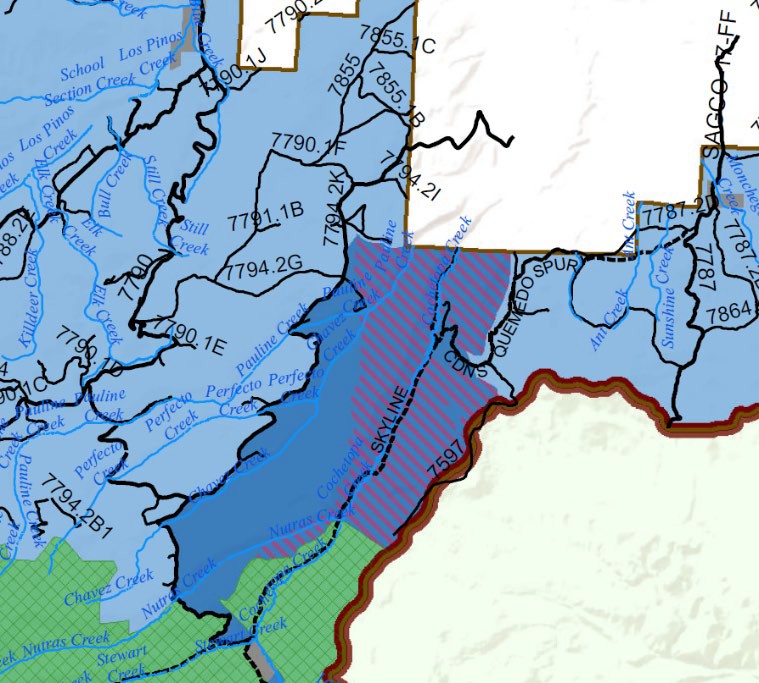

The Final Colorado Roadless Rule decision identified 901,100 acres of suitable roadless areas on the GMUG and also removed 281,500 acres of lands no longer having the required characteristics and added another 124,200 acres that had gained this characteristic when compared to the 2001 National Roadless Rule inventory. 25 While the Colorado Roadless Rule clearly identifies the scope of the inventory on the GMUG, this is no way correlates to the 3.1 Management designation boundary which the Proposal summaries as follows26:

The Organizations are simply unable to comment on the decision-making process that altered the current inventory so completely as this information simply is not provided in any way in the Proposal. This is simply unacceptable.

In addition to significant changes in Roadless area boundaries on the GMUG, the Colorado Roadless Rule introduced the concept of two levels of characteristics to be inventoried. These are identified as “Colorado Roadless Area” and “Upper Tier” and they are significantly different in terms of actions inventoried and those that are prohibited. Despite these significantly different inventory classes, Colorado Roadless areas and Upper Tier roadless areas management is not discussed in the EIS in any manner. Rather the Proposal seeks to take a multiple layer inventory process and manage it as a single management standard, which is the 3.1 Management Area. This is simply unacceptable.

In the development of the upper tier and Colorado Roadless area designations several characteristics were addressed in significantly different manners in the EIS and the scope of how these characteristics were found suitable was a major topic of discussion. The GMUG Alternative 2 of the Colorado Roadless Rule identified 130,300 acres as suitable for upper tier designation. In Alternative 4 of the Colorado Roadless Rule this acreage jumped to 544,900.27

There is simply no discussion of how decisions are consistent with inventory and analysis of areas for possible management in alignment with these characteristics of a roadless area or upper tier area. The words “Upper Tier” or “Colorado Roadless area” simply are not addressed in the Proposal outside the Wilderness inventory. In this discussion, USFS staff simply said these designations were put in the right category. After the concerns above on existing management identified above, we have no idea how this could be justified. We again have serious concerns on how those decisions were made and impacts this may or may not have on decisions such as route density etc.

Proposed resolution of issue 4.

The Organizations would ask that the name of the management area be changed to something other than a Roadless area, simply to avoid confusion of the public moving forward. Roadless areas are an inventory of limited characteristics of an area and not a management standard and this clear distinction should remain. Additionally, the Organizations would request that additional usages, such as grazing or oil and gas management of these areas be addressed simply to avoid confusion and conflict moving forward.

5(a) Our partnerships on wildlife challenges are significant and represent an issue we take very seriously.