U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,

Public Comments Processing,

Attn: FWS–R6–ES–2021–0134,

MS: PRB/3W, 5275

Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA 22041–3803

RE: Threatened Species Status with Section 4(d) Rule for the Silverspot Butterfly

Docket No. FWS–R6–ES–2021–0134; FF09E21000 FXES1111090FEDR 223

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the vigorous opposition of the above Organizations with regard to the Proposed species status of the Silverspot Butterfly (“The Proposal”). Prior to addressing the specific concerns, the Organizations have regarding the Proposal, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 250,000 registered OHV users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations. The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a largely volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite the more than 30,000 winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport. For purposes of these comments, TPA, CSA and COHVCO will be referred to as “the Organizations”. The Organizations have been actively involved in numerous esa listing efforts, such as lynx, grey wolves, wolverine and grouse. We have also actively involved in numerous efforts on species management hosted by groups like the US Fish and Wildlife Service, state wildlife agencies and the Western Governors Association efforts on Species management. These efforts have included a wide range of participation includes panelists in round table discussions at events, financially supporting Wolverine research in Idaho to funding development and distribution of the 3rd version of Lynx Conservation Assessment and strategy.

We must ask what has changed when compared to previous determinations that the Silverspot butterfly species and various DPS was not the basis for listing. This concern is highlighted by the fact the listing documents undertake a significant discussion about what the proper species classification is for the Silverspot. The highly ambiguous nature of the listing regarding many issues ranging from: 1. The mere definition and description of the subspecies; 2. The inclusion and exclusion of many factors such as exclusion of pesticides as a possible impact to the species; and 3. Inclusion of habitat fragmentation as a threat without addressing the wide-ranging nature of habitat fragmentation. The current proposal clearly identifies that the species population is stable and is expected to remain so for the foreseeable future, which means there is time to more completely understand the species, describe and define the species and then address the challenges it is facing.

The lack of clarity on these basic issues will lead to huge confusion for the public and guidance that lacks clarity in the recovery plan. There is a significant lack of analysis and highly theoretical nature of analysis of possible recreational impacts on butterflies generally which results in conclusions that are horribly internally conflicting. The only recreational activity even mentioned in the proposed rule is collecting and this is found to be a minimal threat. The Organizations are intimately familiar with decisions and efforts where one agency explicitly and clearly states recreation is not an issue for the species and there should be no change to management of recreation due to the listing and subsequent efforts by other agencies place significant restrictions on recreation when habitat fragmentation is even mentioned. This is exemplified by Wolverine listing efforts, Mexican Owl listings and far too many others to address. This type of concern explodes when the listing decision is as unclear and conflicting as the Proposal is. Establishing a clear foundational structure for any listing is critically necessary to avoid conclusions that lack factual basis, such as the recent management of bumble bees as Fish in California.[1] Proposal is totally premature as basic questions are not addressed and may also lead to conclusions and management that lack any factual basis and undermine public support for species management more generally.

1a. The landscape challenges surrounding insects on the ESA cannot be resolved with poor listing decisions for species.

The Organizations must recognize there is significant ongoing discussions on the ability of the ESA to list insects generally. These discussions have centered around concerns such as physical characteristics of insects failing to identify the species, the inability of habitat to be identified with any accuracy or the lack of understanding around the challenges to the species. While there is no uniform path forward identified, the general consensus appears to be that species should not be listed without resolving these challenges, as the management process of the ESA simply does not work for insect and several other species.

Several authors have recommended the following rather novel process, but legally questionable resolution to address insect related issues for ESA purposes:

“In light of FWS’s reluctance to change, the best solution to the problem is an increase in knowledge about insect conservation and the use of surrogate species to protect endangered and threatened species until the necessary knowledge base has been established.”[2]

While this is a novel and we believe unadvisable resolution of this issue, it recognizes there are currently significant unresolved issues with the ESA process for insect management. American Entomological Society echoes these concerns in their position paper addressing the challenges of providing ESA protections as follows:

“ESA advocates the following positions regarding the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973: • The decision to protect a species should be made on the basis of current scientific evidence, to inform listing and prioritization schemes. • Insect conservation is critical to healthy ecosystems, but a clear bias toward plants and vertebrates exists in the listing process. The population dynamics, interpretations of species boundaries, taxonomic conventions, and other challenges related to identifying and counting insects should be accounted for when assessing their status. Here, the Endangered Species Act needs improvement.[3]’

Many of the pitfalls that are faced when listing insects on the ESA, such as accurate descriptions of physical characteristics of the species are exhibited in this listing. The listing and related rules do a commendable job addressing the significant conflict among researchers on how the species is even defined. This type of foundational concern in a listing is a concern. The listing also fails to address factors that have heavily impacted other species of butterfly and how these factors were found to be excluded or irrelevant to the current listing. Pesticides would be an example of this issue.

While we are aware there is concern about the species, this does not create a basis for listing. Uncertainty does not result in a need for a listing, but rather indicates a need for more research to address the foundational requirements for a meaningful listing analysis. The need for listing is further mitigated by the fact that the species is stable currently and only forecast to decline from climate change. For the Organizations, the 30kft level discussion on the applicability of the ESA to insects is a major concern and should be addressed by the legislature before listings occur. The Organizations are further concerned that these types of listing are hugely problematic when the protections of the ESA are addressed for the species. Those challenges are addressed subsequently in these comments. The Organizations are very concerned that generally the listing will simply create management problems with little benefit to the species.

1b. Conservation efforts without scientific process and standards do not yield results but only conflict.

The Organizations would like to address the larger scale concerns around the Proposal. As we noted earlier, the Organizations have been involved in dozens of ESA listings, Conservation Assessments and Strategies and other projects to support a wide range of species. Some of these efforts we have been involved with for more than 30 years. While these efforts have spanned decades, we are not sure how much difference it has made for many species and we are not aware of a single species that has been the target of these efforts that has actually been delisted. Globally recognized wildlife researchers have recently identified this as a significant management challenge for all involved, which they outlined this situation as follows:

“However, problems can arise at the outset from the way these issues are framed. For instance, in the field of human–wildlife conflicts they are often presented as a struggle between animals and people, and the conflict between different human interest groups is ignored (Peterson et al., 2010;Redpath et al., 2013). In reality, most of these conflicts are between conservation interests and other human interests, such as farming, hunting or fishing (Redpath et al., 2015b). Representing these issues as conflicts between farmers and predators is misleading and limits the opportunities for management. To help delineate these two dimensions, Young et al. (2010) distinguished between human–wildlife impacts and human–human conflicts.

The problem of framing is further compounded by the fact that it is often the conservationists who, although not neutral in such settings, are the ones driving the development of management strategies. Clearly, they are likely to be biased in seeking outcomes that benefit conservation, and may not be trusted by the other party or parties….Second, policy-makers often want quick fixes and rapid conflict resolution. Yet, these conflicts are ubiquitous and persistent. We know of no example where a wildlife conflict is considered to have been resolved. Indeed, there are very few instances where they have been effectively managed in the long term to reduce conflict, although there have been some short-term, local successes.”[4]

The Organizations could not agree with this conclusion any more vigorously. We simply completely agree with this concern. This type of a management concern is not addressed by listing species that really cannot be described, based on highly modeled habitat, and scientific analysis that fails to address basic consistency of analysis. For this reason alone, the Organizations must oppose the listing of the species which has been found stable currently and for decades to come. We just need better analysis.

2a. ESA Listings based on scientific conflict and uncertainty are legally insufficient.

The Organizations are concerned the proposed listing is highly theoretical and provides little on the ground analysis or information to support many of the conclusions that are provided, such as how was the range of the species established as many of the factors identified in the listing in no way correspond to the range asserted in the listing. This lack of actual information is problematic on many issues, such as the consistency in the application of modeling of factors and how these models relate to the legal requirements for listing a species on the ESA. ESA listing that are based on modeling of possible future impacts are problematic, as evidenced by the 2020 withdraw of the proposed Wolverine listing which was withdrawn based on insufficient modeling of the impacts and challenges.

The Proposal identifies the stability of the population as follows:

“We find that the Silverspot is not currently in danger of extinction because the subspecies is still widespread with multiple populations of various sizes and resiliency spread cross its range, capturing known genetic and ecological variation. Therefore, the subspecies currently has sufficient redundancy and representation to withstand catastrophic events and maintain adaptability to changes.”

The decline of the stable population is only forecast as is clearly identified in the Proposal as follows:

“However, we expect that the stressors, individually and cumulatively, will reduce resiliency, redundancy, and representation within all parts of the range within the foreseeable future in light of future climate change effects.”[5]

This forecasting is concerning as the only change for the Silverspot since last attempt to list is the further division of a species into more subspecies and this has been occurring since the late 1970s. We doubt this type of management future could ever have been predicted at the time of the previous listings. We are also concerned that in previous listings the primary threat to the species was identified as human disturbance. These challenges are outlined in great detail in the Hammond article[6] published in 1984 identified in the SSA several times, but at no point is the change in what best available science even addressed. Candidly the situation presented in the Hammond article presents a far more compelling need for listing and grim forecast for the species. Thankfully this has not occurred but we must question how changes such as this can occur without discussion of the analysis and process that the conclusion has resulted from. Clearly this is an example of why forecasting is problematic in the listing process. Given the huge number of subspecies that are now occupying almost overlapping habitat areas, the Organizations have to question how accurate counts are achieved and habitat is drawn with the challenges in even describing the species currently. While researchers should be commended for their on-going efforts around models of insect species as this is scientifically interesting, this is not the basis for listing species on the ESA as this effort falls well short of the legal requirements of listing.

The Organizations would also express concern around the premise that an ESA listing may be found to be sufficient for further management actions in the face of this type of uncertainty, as this flies in the face of best available science and management process. Best available science and basic management decision making mandates that in these types of situations, the inaccurate modeling effort that is being relied on as the basis for the management action be returned for further development and refinement to improve accuracy. Inaccurate modeling of issues can have catastrophic unintended consequences when management actions are being taken on the model. Until basic information on the species can be clearly defined and described, any listing is premature as the lack of science is not science but rather evidence of the need for further work on the issue.

2b. Significant clarity must be provided for the identification of these various subspecies.

We are very concerned that without some way to actually describe and identify the species every butterfly that is seen in possible habitat will be assumed to be Endangered and this will create nothing but conflict and management problems. As previously mentioned, the Organizations are heavily involved with ESA management of several species and these are species that are easily identified based on their physical characteristics by the public. Members of the public are able to identify a lynx and separate it from a mountain lion. Most of the public is able to consistently identify a wolf from a fox or coyote. Even with these generally recognized species boundaries, we have encountered significant concerns and unintended consequences from listing and management of these species. Many of the public believe that simply seeing a creature in the wild creates the need for management action. These concerns are exponently expanded when the listed species cannot be accurately identified as often the public cannot separate butterflies from moths etc. We want to avoid management decisions being based on the fact the public may have saw a butterfly or a moth or other species that may or may not be listed.

The need for a clear and identifiable description of what is a possibly protected species and what is not is exponently compounded by the fact the subspecies can reproduce with each other and create hybrid species. A review of the SSA reveals almost every color in the rainbow is identified as characteristic of the possible subspecies, and they are all about the average size of a butterfly. The SSA clearly states the butterflies will display orange, yellow, brown, black, white or silver. The SSA continues that hybrid species may introduce even more variation into the physical characteristics of the species. Our concerns are again compounded by the huge numbers of environmental factors that may impact these characteristics in insects, including food sources, time the sun, intensity of the sun, parasites, temperature to name a few.

Extensive books have been written about the need for these type of thresholds in the management of wildlife and the ESA listing process from agency partners that work with the USFWS.[7] This type of foundational structure is critically necessary to avoid conclusions that lack factual basis, such as the recent management of bumble bees as fish in California. These types of conclusions simply must be avoided, no matter how well intentioned they are, as the erosion of public support for species management that can result from decisions that cannot be factually defended is significant.

Our concerns are compounded by the fact the SSA goes into great detail around the scientific conflict that has recently occurred around what is the proper species designation and how many subspecies there are. Most of these decisions have been made in the last 3-5 years. This type of decision reflects exactly the type of uncertainty we believe still persists it the insect listing arena and simply must be resolved with some level of scientific certainty before listing. Given the significant conflict around what species this falls into and how many subspecies there actually are, the hybrid issue is very significant and completely overlooked in the SSA. What is the status of these hybrids as the SSA states they are not part of the species to be listed? This is a serious concern as without a high-quality description of the species, we are unsure how any management of the species can occur.

2c. Best available science concludes that management may not be possible if there is intrinsic uncertainty in the process that cannot be identified accurately.

The Organizations are very concerned that the species can’t be described with sufficient accuracy to list the species. This type of foundational uncertainty for a listing can have major impacts throughout the management process. We are very concerned about these unintended impacts of the listing. Extensive concern about the proper process to address all forms of uncertainty in the listing process have been expressed by wildlife management experts in their efforts to quantify and manage uncertainty in wildlife management efforts. This concern was recently summarized as follows:

“Unfortunately, ecological systems are enormously variable at just about every scale that we study them (Holling, 1973). This variability has numerous sources and, collectively, they contribute to what may be known as ‘uncertainty’. In recognizing the role of uncertainty, it is important to recognize that this may arise both as an intrinsic property of the system as well as a nuisance through inadequate data or observation. In terms of intrinsic sources, for example, spatial variability results from variations in conditions from place to place (Tilman & Karieva, 1997), while temporal variability similarly results from variations in systems through time (Huston, 1994). On the other hand, the measurements of the system may contain inaccuracies. For instance, observational variance is a consequence of our inability to perfectly measure systems, instead relying on sampling in order to build up a picture of the dynamical properties of the system (Dennis et al., 2006; Freckleton et al.,2006).”[8]

Similar concerns around the uncertainty of research and forecasting processes have been the basis of analysis of decades of research and theory development in the ESA realm. Similar concerns have been expressed as early as the 1980s as follows:

“Complexities of nature, obscurity of many species’ life history, and changing environmental conditions make it difficult to assess the accuracy of extinction risk models. Proposals to list very small populations with known threats and unequivocal population status are the exception today in the coterminous United States. There are few, if any, of the California condor-like species that are not already listed. Many of the species we evaluate now are wide-ranging, with little information available on their life histories. Some of these species have population trend data suggesting declines, but populations may remain in the tens to hundreds of thousands of individuals.”[9]

The Woods article above identifies three species where identification of the species is challenging and the intrinsic problems this creates for management decision making. Almost 50 years later, resolving this type of uncertainty remains a challenge. The British Ecological Society recently proposed proposes to manage this type of systemic uncertainty into two large classifications to try and mitigate the impacts of uncertainty in wildlife management. These two classifications are as follows:

“Broadly speaking, it is useful to distinguish intrinsic uncertainty (analogous to the variance in model parameters in an ecological or statistical model) from knowledge uncertainty (by analogy with the measurement error or lack of data in a model). The reason for making the distinction between these two types of uncertainty is important: one is a property of the system itself, while the other is caused by a lack of understanding or data. The two are interactive, and this is perhaps the greatest challenge to making robust predictions in management. If the management outcomes are uncertain both in terms of intrinsic variability and knowledge then they will be largely unpredictable. In this circumstance, it is necessary to question the recommendations given, as well as to consider whether the approach to prediction is the correct one.”[10]

The Sutherland book then undertakes an extensive discussion of possible ways to address informational uncertainty and create a model that provides predictable results that may support a management decision. Given the description of the challenges being faced in the management of the Silverspot butterfly, the Organizations submit that the inability to accurately describe the species falls into the category of intrinsic uncertainty and may not be resolvable.

The Sutherland book further continues and provides an example of what can happen when these factors are not accurately addressed in management decision making. This example is as follows:

“As an example, in the UK there was a programme for government- hired shooters to exterminate ruddy ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis). During the cull, coot (Fulica atra), black-necked grebe (Podiceps nigricollis), common pochard (Aythya ferina) and common scoter (Melanitta nigra) individuals were also shot (Henderson, 2009). This resulted in part from inadequate communication with shooters (Henderson, 2009), who were not ornithologists and failed to distinguish between species. Consequently, there is a possibility of confusion, with procedures subsequently being developed to ensure that confusion is minimised.” [11]

Other researchers have addressed uncertainty in species management processes, modeling of population trends and listing efforts for easily identifiable and describable species as follows:

“Hence, accurate information on population trends is lacking for most species. These challenges to understanding sustainability of elasmobranch fisheries and using precautionary approaches for their management are compounded further by multi-species fisheries and poor species-specific monitoring (Barker and Schluessel, 2005; Lack and Sant, 2009; Dulvy et al., 2017) …. Recently, there has been increasing awareness of the importance of considering multiple sources of uncertainty in demographic parameter estimation and risk assessment (Simpfendorfer et al., 2011; Corte´s et al., 2015; Jaiteh et al., 2017a). In addition, demographic modelling frameworks quantify the degree of caution that should be exercised for their sustainable management and can have major implications for the conservation of species (Caswell et al., 1998; Corte´s, 2002; Corte´s et al., 2015). The two main sources of uncertainty that can be easily accounted for in a modelling framework are measurement error (or trait error), stemming from uncertainty in the empirical estimation of a life history parameter (Harwood and Stokes, 2003; Quiroz et al., 2010), and coefficient error, which is derived from the uncertainty in the values of the coefficients of a model (e.g., uncertainty around the intercept of a linear model, see Quiroz et al., 2010). While multiple sources of uncertainty can be readily accounted for in stock assessments, this has not happened to the same extent in data-poor situations, particularly in commonly used unstructured models (for a recent example see Jaiteh et al., 2017a).” [12]

The description of species and forecasting of population trends has been a challenge in the listing process since the ESA was adopted. It is well documented that failures to resolve the basic challenges can cause significant problems with management efforts undertaken subsequently. The Organizations submit that exactly these types of challenges will plague any effort to manage the Silverspot as proposed. The Organizations submit the uncertainty intrinsic in the current proposal is FAR greater than any addressed in these articles. Without resolution of the intrinsic uncertainty resulting from the inability to describe the species, communication of information will simply be impossible.

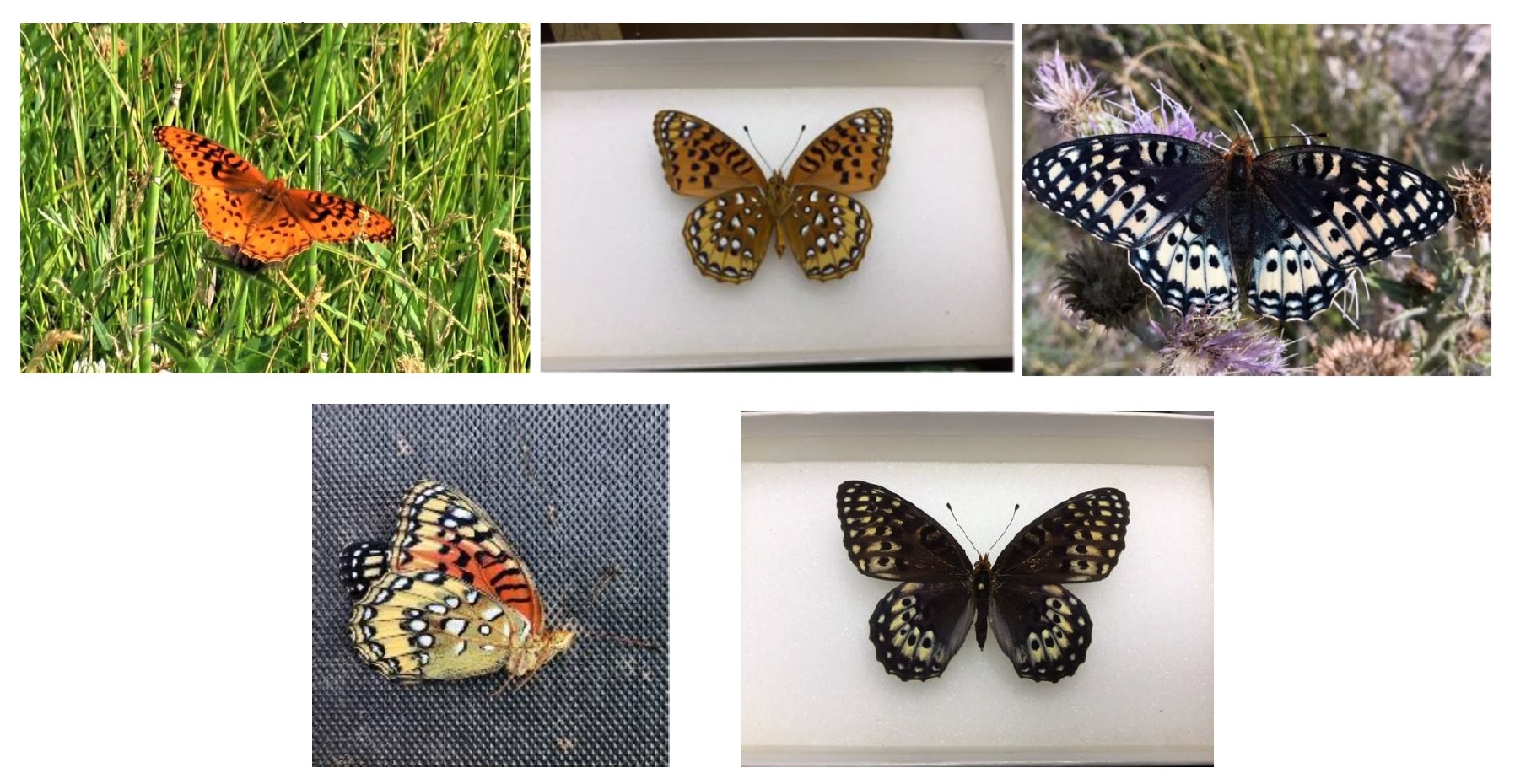

This inherent conflict in describing the Silverspot could not be more apparent than is presented in the series of pictures from the SSA.

The ability of the species to be identified as a single species from these pictures is exceptionally limited at best. What is concerning is we must assume these are the best pictures available for the listing and most pictures will fail to provide anything close to this level of detail and quality. This would represent the type of intrinsic uncertainty or observational variance uncertainty that is discussed as challenges to listing or management in the Review. This is type of uncertainty is a major problem that must be addressed in any management effort for a species as it is concluded when these types of issues are not able to be resolved the management outcomes will be largely unpredictable.

3a. Without a describable species, how is modeling and management of habitat undertaken?

The inability of the species to be accurately described and classified gives rise to a host of other problems in subsequent species management efforts, such as habitat identification or avoiding unintended management actions taken in the generalized habitat information already provided. Without a good description how do we not have problems with the 2018 US Supreme Court’s unanimous Weyerhaeuser decision and the sufficiency of the listing and related petition under Rule 424.14. While the USFWS recently withdrew the proposed definition of habitat required by Weyerhaeuser, this does not mitigate the legal requirements of the Weyerhaeuser decision. These challenges are insurmountable when the species cannot be accurately described or separated from other species that are not proposed for listing.

The Organizations are very concerned that the current documentation is highly theoretical in nature and far from a settled scientific model moving forward. The Proposal relies on some type of model or forecast for almost every aspect of the analysis, compounding risk of inaccuracy significantly. The use of modeling in the ESA has been an issue that has been the basis of dozens of treatises and texts and is far from a resolved issue.[13] These reviews have consistently identified the need for the scientific community to provide legally sufficient basis for species management. This standard has been summarized as follows:

“Given the importance of maintaining biodiversity for both ethical and practical reasons- foe example to sustain environmental goods and services critical to human welfare (Hooper et al 2005)- it is imperative that the scientific community provide land managers with the knowledge and tools needed to meet their conservation mandate.”[14]

Other researchers have stated this standard in the management as listing of identifiable species, such as the Mexican gray wolf as follows:

“Policy-related uncertainty originated from contrasts in thresholds for acceptable risk and disagreement as to how to define endangered species recovery. Rather than turning to PVA to produce politically acceptable definitions of recovery that appear science-based, agencies should clarify the nexus between science and policy elements in their decision processes. The limitations we identify in endangered-species policy and how PVAs are conducted as part of recovery planning must be addressed if PVAs are to fulfill their potential to increase the odds of successful conservation outcomes.”[15]

These treatises also provide highly detailed discussions on the management of uncertainly in the assumptions and data in the species/habitat modeling process. Listing a species that is stable and only facing long term challenges is simply never recommended. Rather, listing a species based on a lack of information on the species is a failure of basic scientific processes around the modeling of any habitat areas for a species. In habitat discussions driven by the ESA, too often processes fail in correcting basic modeling errors, as is mandated by the scientific process for modeling any activity. Instead, these modeling errors which are not based on scientific process are sought to be normalized in a rushed effort to protect a species.

The Organizations vigorously assert that the problems with modeling the species that cannot be described or scientifically defined accurately are compounded when applications of habitat designation standards are undertaken. While we are aware the Proposal is not designating critical habitat, it is identifying habitat or range in the SSA which creates a myriad of problems by itself. It has been our experience that even when critical habitat is not identified for a species but habitat range is identified, many will attempt to use the modeled range as critical habitat in planning. This is a problem. This problem is compounded by the fact that often the lack of critical habitat for a species is an issue that can be litigated for years. This could not be more exemplified than by the recent successful court challenge to the USFWS decision not to designate critical habitat for the Canadian Lynx. This decision comes down more than 20 years after the lynx was originally listed for ESA purposes. Not designating habitat in the Proposal does not mitigate our concerns but rather compounds them as the last thing the Organizations want to participate in is decades of litigation on a species, we don’t present at threat too.

The challenge of modeling habitat is immense and only expanded when the species cannot be defined. Recent USFWS efforts have highlighted the habitat designation challenges for identifiable species as follows:

“In particular, the proposed definition is written so as to include unoccupied habitat, whereas many of the definitions in the ecological literature that we reviewed did not appear to consider unoccupied areas.”

The concern of the scientific community around management of poorly defined habitat is not minor. The mandate of applying best available science (“BAS”) is one of the cornerstones of the entire Endangered Species Act and is specifically applicable to the designation of both basic habitat and critical habitat. It is the Organizations position that best available science should be consistently applied throughout the ESA. A few examples of the BAS requirement would include §4(b)(1)(A) of the ESA which requires agencies to make listing decisions based:

“On the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available…”

Similarly, §4(b)(2) specifically requires managers addressing critical habitat designations and review to:

“Designated critical habitat and made revisions thereto, under subsection (a)(3) on the basis of the best scientific data available…”

Section 7(a)(2) of the Act continues applying this BAS cornerstone of the Act to the consultation process as follows:

“In fulfilling the requirements of this paragraph, each agency shall use the best scientific and commercial data available.”

While the process for modeling of any activity has not been a hot bed of legislative activity, modeling of complex activities and relationships occurs consistently throughout the world on a huge number of issues and has been the basis of extensive scientific and scholarly analysis. While there are an exhaustive number of models for almost any activity, the Organizations are aware that all modeling guidelines require some basic review of the model to ensure the model is accurately predicting the behavior that is sought to be modeled. While no model is perfect in predicting all behavior, there needs to be some level of correlation between the model and the behavior modeled. If the model does not accurately forecast or provide consistent results, the model is fixed and management action is not taken. A good general summary of the modeling and simulation process is provided by Wikipedia.com, which provides the following general guidance on modeling of behaviors

“Modelling as a substitute for direct measurement and experimentation. Within modelling and simulation, a model is a task-driven, purposeful simplification and abstraction of a perception of reality, shaped by physical, legal, and cognitive constraints.[12] It is task-driven, because a model is captured with a certain question or task in mind. Simplifications leave all the known and observed entities and their relation out that are not important for the task. Abstraction aggregates information that is important, but not needed in the same detail as the object of interest. Both activities, simplification and abstraction, are done purposefully. However, they are done based on a perception of reality. This perception is already a model in itself, as it comes with a physical constraint. There are also constraints on what we are able to legally observe with our current tools and methods, and cognitive constraints which limit what we are able to explain with our current theories.

Evaluating a model: A model is evaluated first and foremost by its consistency to empirical data; any model inconsistent with reproducible observations must be modified or rejected. One way to modify the model is by restricting the domain over which it is credited with having high validity. A case in point is Newtonian physics, which is highly useful except for the very small, the very fast, and the very massive phenomena of the universe. However, a fit to empirical data alone is not sufficient for a model to be accepted as valid. Other factors important in evaluating a model include:

-

- Ability to explain past observations

- Ability to predict future observations

- Cost of use, especially in combination with other models

- Refutability, enabling estimation of the degree of confidence in the model

- Simplicity, or even aesthetic appeal” [16]

As briefly outlined in the Wikipedia definition, the evaluation and revision of any modeling or simulation of behavior is a critical step in the modeling process and without success at this step the model should be modified or rejected entirely. This double check of the accuracy of the model to predict behavior is a basic review for any model of activity or behavior. While the list of modeling guidelines is overwhelming, recognition of the requirement for a double checking of the accuracy of the model under non statutory situations. For creation of a business model, Entrepreneur magazine recommends the following step in the development of a business model:

“2. Confirm that your product or service solves the problem. Once you have a prototype or alpha version, expose it to real customers to see if you get the same excitement and delight that you feel. Look for feedback on how to make it a better fit. If it doesn’t relieve the pain, or doesn’t work, no business model will save you.”[17]

A similar need to double check that any model is accurately reflecting the behavior sought to be modeled in the development of mathematical models. This requirement in mathematical modeling efforts is outlined by experts as follows:

“3. Determine how the model could be improved. In order to make your model useful for further applications, you need to consider how it could be improved. Are there any variables that you should have considered? Are there any restrictions that could be lifted? Try to find the best way to improve upon your model before you use it again.[8]”[18]

Similar to the modeling of business activities and mathematical theory, best available science on the modeling of wildlife habitat also has an exceptionally well-defined process for development of species or habitat models. This process includes a step to review that the results of the model are corresponding with the actual life activity of the species. This process of modeling wildlife habitat has been outlined as follows:

“Modeling wildlife habitat over this range of scales requires many assumptions about the relationships between wildlife population metrics and habitat occurrence, quality, and spatial distribution. Standard modeling protocol is to explicitly state all assumptions early in the process; substantiate those assumptions with field data, published information, or expert opinion; hypothesize the relationships among wildlife and their habitat; and use the modeling framework to evaluate sensitivities and produce output. One critical assumption underlying this protocol is that habitat is accurately characterized at ecologically relevant scales to the organism(s) of interest.”[19]

Other experts have provided the following summary of the wildlife habitat modeling process:

“The Process of model evaluation and validation is a critical step in modeling. However, this evaluation should not focus on how well the model captures “truth” (verification) but how well the model performs for its intended purpose.”[20]

Without exaggeration there are libraries full of scholarly materials addressing the proper methodology for the development of habitat models for wildlife, and these range from discussions at a very general level to the specific process that was used to model habitat for a species. This level of vigor in order to establish a defensible scientific model of habitat is often simply not present in the ESA listing process.

Even when addressing wildlife habitat, best available science clearly identifies the need to ensure modeling of habitat areas is actually reflecting the species and the areas the species depends upon for basic life activities. While best available science clearly requires if a model does not accurately reflect the modeled behavior, this is a basis for review and modification of the model and not moving forward with the recommended actions of the model. If the modeling accuracy cannot be improved to a scientifically defensible level, the modeling effort is stopped at some point. This simply is not how modeling of critical habitat has occurred in our experiences under the ESA process as often the rush to protect the species overwhelms any discussion of revision of models due to poor performance of the model in predicting behavior. The Proposal would be a good example of the relationship of these types of challenges in the management of a possible species. Challenges are insurmountable in these discussions without accurate descriptions of the species and some type of analysis being available that is not forecast.

The Organizations believe a comparison to the facts around the listing of the Gopher frog which was struck down in the recent Weyerhaeuser Supreme Court decision and the current proposal will clarify our concerns about the poor resolution of the management of uncertainty. The gopher frog listing provided the following criteria for habitat which are summarized as small ponds that hold reasonable quality water at least 195 days of the year, a lack of predatory fish; and an open canopy herbaceous forest. [21] The comically broad nature of these modeling factors is immediately apparent, as under these factors the gopher frog could be living in almost any pond in the country. It should be noted that these factors could be applied to a huge number of OTHER species totally unrelated to the gopher frog as well. Almost no pond in the country could be excluded with these modeling factors despite the fact the gopher frog has never lived in most of the country. This is an example of a failed habitat model, which could be corrected with a more detailed discussion of why the area is thought to be suitable. The Proposal falls victim to the same overly broad analysis failure as there is no meaningful description of the species that can clarify what is a Silverspot butterfly and what is not. Hybridization of the species compounds this failure.

Our recommendation for the Proposal is the same as reached by the Court in Weyerhaeuser, the decision cannot be supported without further analysis.

3b. The inability to define habitat as led to conclusions that simply cannot be factually or legally defended in the Proposal.

This question is more than timely with the recent withdrawal of the habitat definition by the service, the uncertainty of the definition expands risk. Regardless of the final decision by the Service on the habitat definition, best available science still must be complied with. After reviewing many of the definitions that are provided in scientific research, the Organizations believe that the definition of habitat provided by the researchers is stronger than either that is current provided by the Service. The Organizations have attached a survey of relevant researchers’ definitions of wildlife habitat that was prepared Elsevier publishing as part of their Science Direct journal.[22] We have attached a copy of this document to these comments as Exhibit “2”.

While we are aware the listing technically is not designating critical habitat, the listing will impact activities in area identified as range, and the failure to properly define habitat areas has led to conclusions regarding various challenges to the habitat areas. The Organizations must express serious concerns about the arbitrary decision that habitat fragmentation as a threat to the species while pesticide usage is not. Best available science outlines the significant overlap of the use of pesticides as a component of habitat fragmentation. Example would be the use of pesticides and its impacts on the species. Proposed Rule provides:

“In this proposed rule, we will discuss only those factors in detail that could meaningfully impact the status of the subspecies. Habitat loss and fragmentation, human-caused hydrologic alteration, livestock grazing, genetic isolation, exotic plant invasion, climate change, climate events, larval desiccation, and collecting are all factors that influence or could influence the subspecies’ viability. Those risks that are not known to have effects on Silverspot populations, such as disease, predation, prescribed burning or wildfire, and pesticides, are not discussed here but are evaluated in the SSA report.”[23]

Conflict with this allocation of threats and best available science on the impacts of pesticides on insects is immediate. This research has been summarized as follows:

“There is no doubt that pesticides can be enormously beneficial in both agriculture and preventive medicine, for example to increase (the quality of) crop yields, to maintain healthy livestock and to prevent the spread of diseases (Oerke, 2006; Cooper and Dobson, 2007; Aktar et al., 2009; Benelli and Mehlhorn, 2016; Guedes et al., 2016). However, due care is needed for their use in an effective manner. Not only do we need to carefully establish the mode of action of pesticides, but also the effects of pesticides on both their intended targets and non-target species. It is clear that where innocent bystanders of pesticides find their natural habitat replaced or reduced by agricultural practices they are doubly affected (Potts et al., 2016). One such group of insects are Lepidoptera which may comprise good indicator species for the non-target impacts of pesticides. Our relationship with Lepidoptera is a complex one. On the one hand they are the focus of considerable conservation efforts, predominantly butterflies (Brereton et al., 2011; Potts et al., 2016), but on the other hand 70% of agricultural pests are Lepidoptera, in particular many moth species and a few butterflies.” [24]

The Braak et al articles then continues its discussion of the significant impacts of pesticides generally in an urban setting as follows:

“Furthermore, we also need to consider the impact of non-675 industrial use of pesticides in gardens, parks and other recreation areas such as golf courses, 676 which are increasingly important in agricultural and urbanized landscapes (Colding and 677 Folke, 2009).”[25]

Similar research on monarch butterflies has expressed significant concerns about the impacts of genetic modifications designed to replace pesticides have on habitat and the species as a whole. These concerns are as follows:

“Habitat loss in the overwintering sites in Mexico and California is well documented (Brower et al. 2002; Ramirez et al. 2006), although no direct empirical link between declining overwintering habitat and monarch numbers exists. In addition, the growing use of glyphosate-tolerant genetically modified crops has reduced larval host plant (milkweed, Asclepias spp) abundances in farm fields across United States and Canada. Increasing acreage of glyphosate-tolerant corn and soybeans are negatively correlated to monarch numbers, with the area of milkweed in farm fields in the United States declining from an estimated 213,000 to 40,300 ha (Pleasants & Oberhauser 2012).”[26]

The pesticide question is asserted to be resolved for some uses as follows in the listing:

“In S. n. nokomis range there is more haying and grazing than cropland, and as a consequence there may be less application of pesticides on or near colonies than in many parts of the U.S. but the amount and type of pesticide use near S. n. nokomis colonies needs to be studied. We currently have no evidence that mortality of the butterfly, bog violet, or native nectar sources have occurred from pesticide use and are not aware that it has currently reduced the viability of the species.”[27]

The Organizations assert this is problematic decision making process for any effort. The problematic decision making continues as activities that support agriculture are identified as threats, such as haying of fields and conversions of habitat for other agricultural activities is identified as a threat to the species as habitat fragmentation. We question how this distinction can be justified with any scientific or factual basis. This conclusion simply lacks any factual basis whatsoever, and would seem to be made in direct conflict to the conclusion that habitat fragmentation is a priority threat to the species.

We are very concerned that habitat fragmentation is often associated with trail usage and other forms of recreation, as this has occurred with other butterfly species.[28] The Organizations are unable to identify any research supporting a conclusion that recreational activity as a threat to the species.[29] Given the arbitrary application of existing research in the manner proposed in the listing, excluding any activity associated with urbanization or fragmentation of the habitat areas will be difficult to impossible. This lack of an established relationship between the challenge and management would be seen as a basis for management, and this is a connection we are unwilling to make.

4. Asserting habitat fragmentation is a primary threat to the species without identifying habitat is factually and legally indefensible.

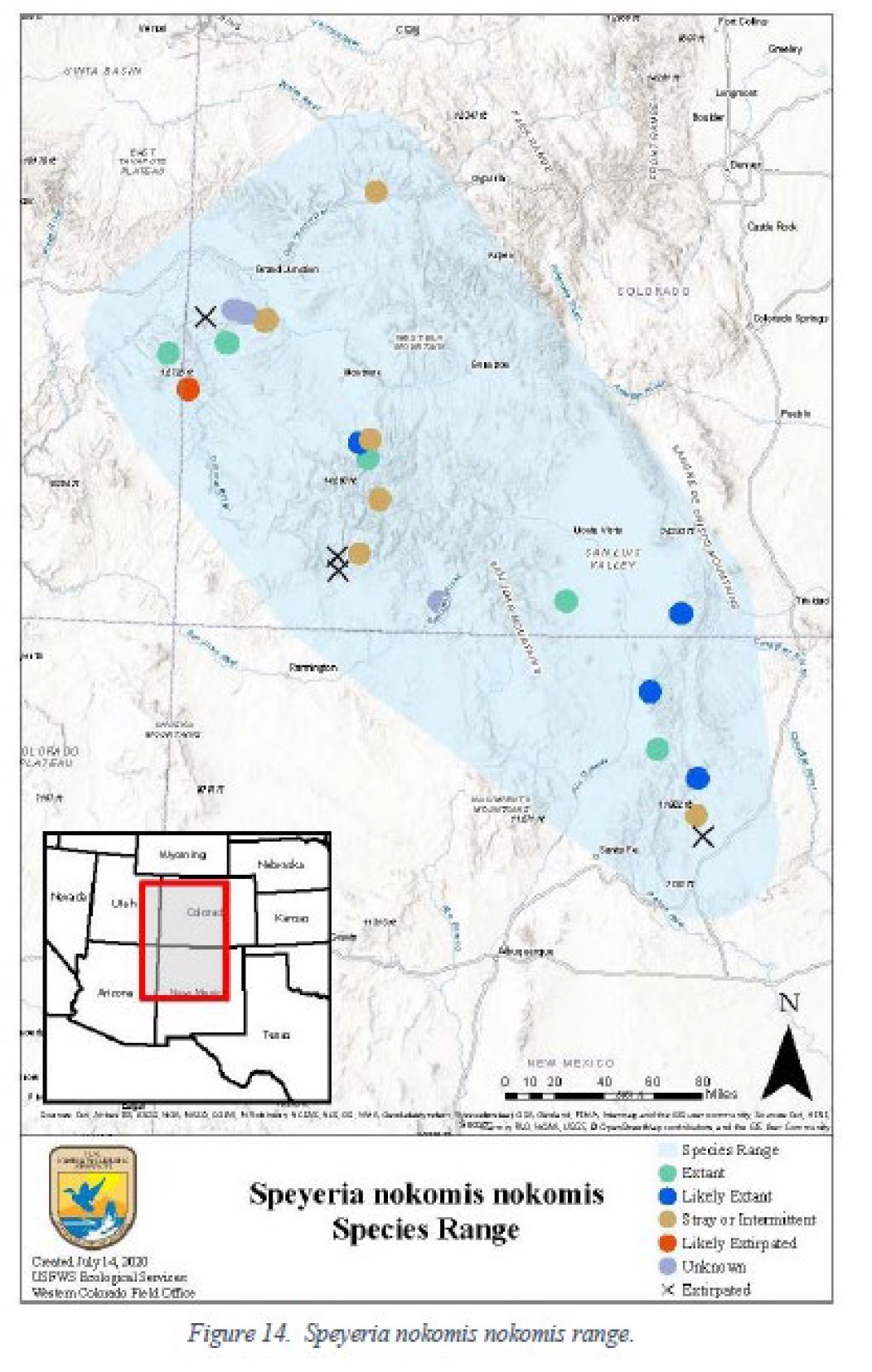

It is with the above structure of scientific and legal analysis, the Organizations submit that the listing of species that eludes accurate description and relies on habitat/range that is modeled is problematic at best. This concern extends to the determination that habitat fragmentation is a major threat to the species but no habitat is identified. This seems to be indefensible as a matter of fact and law as this should never happen. How can you determine habitat is fragmenting without identifying what is habitat? Identifying what is habitat would be a critical first step in the determination that the habitat is fragmented. The SSA provides the following species range map:[30]

The SSA identifies the questionable management history of the identification of range and habitat and asserts this problem has been resolved as follows:

“Based on the best available scientific information per recent genetic work, the range of S. n. okomis is now better understood than it has been in over a century (Cong et al. 2019). As stated in section 2.3, the range now excludes the Great Basin and Southwest Utah Mountains area (Population 2), the Uinta Mountains area (Population 3), and the Chuska Mountains area (Population 9) for which inclusion in the S. N. okomis range was previously uncertain (Selby 2007, Figure 3, p.11 and p.14). Genetic mixing between the subspecies appears to occur not far from the known locations of identified subspecies (Cong et al., 2019, p. 21).”[31]

While the Organizations commend the development of greater understanding of the species, this provision does not resolve questions but creates them. Is the current analysis better than previous? Probably. Is the current analysis legally sufficient to support a listing? Definitely not.

The Organizations must raise concern over a foundational conflict in the range map with regard to elevation. Under the SSA the following parameters for elevational habitat for the species is provided:

“S. n. nokomis is known to occur from roughly 5,200 feet to just over 8,300 feet in elevation (Scott Ellis and Mike Fisher, pers. comm., 2020). However, one observation is from 9,250 feet near Silverton, Colorado (SCAN 2020).”[32]

The application of this standard even generally immediately causes huge problems for the mapping of the range, as large tracts of land in the range area are more that 50% higher in elevation than the upper threshold of the habitat range provided in the listing. This mapped Range is one of the largest high-altitude areas in the country but this conflict is never even addressed. This is a foundational problem.

The SSA then proceeds through a HIGHLY sight specific discussion of possible impacts to habitat at 19 different locations ranging in size as small as two acres. A large habitat is 500 acres. Many of these populations are identified has genetically isolated as they are more than 30 miles from other populations. If they are genetically isolated, how has that occurred? How was it determined that the species range only 30 miles?[33] What was the range of the population previously? How was it determined the species range from Gypsum, Colorado to Albuquerque, New Mexico, which is a distance of more than 400 miles? It is again a concern that these site-specific habitat areas are modeled, such as the Montrose/San Juan population, bringing in all the modeling concerns we have identified in other areas of these comments. While we understand species range and species habitat are different standards, we have to question the sheer scale of the difference of these determinations in the listing. Is habitat fragmentation identified on the entire range or the 19 sites? These are critical decisions for our interests as there will be impacts to the entire range despite the analysis addressing at most less than 10,000 acres and possibly down to 500 acres based on the assumption the butterfly only travel 30 miles.

Even more problematic is the fact that habitat fragmentation is identified by weighting some factors of habitat fragmentation while specifically excluding other factors often associated with habitat fragmentation. This questionable decision making is outlined in the Summary of proposal for habitat fragmentation as follows:

“We found habitat loss and fragmentation (Factor A), incompatible livestock grazing (Factor A), human caused hydrologic alteration (Factor A), and genetic isolation (Factor E) to be the main drivers of the subspecies’ current condition, with the addition of the effects of climate change (Factor E) influencing future condition. These stressors all contribute to loss of habitat quantity and quality for the Silverspot and for the bog violet, the plant on which Silverspot larvae exclusively feed. These threats can currently occur anywhere in the range of the Silverspot, and future effects of climate change are expected to be ubiquitous throughout the subspecies’ range. The existing regulatory mechanisms (Factor D) do not significantly affect the subspecies or ameliorate these stressors; thus, these stressors continue and are predicted to increase in prevalence in the future.”[34]

Again, the Organizations must question how such conclusions are reached. We are very concerned that the failure to identify habitat areas, even if they are not provided protection, will lead to massive over application of concerns for the species in management. It has been our experience that often trails are thought to be a concern in this situation and this must be avoided.

Conclusions.

The Organizations must express serious concerns about the basic validity of the proposal on many levels, from the inability of the species to be physically described, to the highly theoretical nature of much of the analysis of threats. As we have outlined, many of these issues are inherent in attempts to list or manage an insect species. Best available science has identified the resolution of the problem is statutory and should not be the basis of listing that are not able to resolve these issues. We must ask what has changed when compared to previous determinations that the Silverspot butterfly species and various DPS was not basis for listing. This concern is highlighted by the fact the listing documents undertake a significant discussion about what the proper species classification is for the Silverspot. The current proposal clearly identifies that the species population is stable and is expected to remain so for the foreseeable future, which means there is time to more completely understand the species, describe and define the species and then address the challenges it is facing.

The highly ambiguous nature of the listing regarding many issues ranging from: 1. The mere definition and description of the subspecies; 2. The inclusion and exclusion of many factors such as exclusion of pesticides as a possible impact to the species; and 3. Inclusion of habitat fragmentation as a threat without addressing the wide-ranging nature of habitat fragmentation. Again, the concept of best available science and the legal requirements of the Endangered Species act require resolution of these issues. Identification of systemic uncertainty and resolving is the basis of significant discussion and these are challenges that can be managed. The lack of science on these issues is not best available science but a lack of science.

The lack of clarity on these basic issues will lead to huge confusion for the public and guidance that lacks clarity in the recovery plan. There is a significant lack of analysis and highly theoretical nature of analysis of possible recreational impacts on butterflies generally which results in conclusions that are horribly internally conflicting. The only recreational activity even mentioned in the proposed rule is collecting and this is found to be a minimal threat. The Organizations are intimately familiar with decisions and efforts where one agency explicitly and clearly states recreation is not an issue for the species and there should be no change to management of recreation due to the listing and subsequent efforts by other agencies place significant restrictions on recreation. This is exemplified by Wolverine listing efforts, Mexican Owl listings and far too many others to address. This type of concern explodes when the listing decision is as unclear and conflicting as the Proposal is. This type of foundational structure is critically necessary to avoid conclusions that lack factual basis, such as the recent management of bumble bees as Fish in California.[35] Proposal is totally premature as basic questions are not addressed and may also lead to conclusions and management that lack any factual basis and undermine public support for species management more generally.

Please feel free to contact Scott Jones, Esq. at 518-281-5810 or via email at scott.jones46@yahoo.com or Chad Hixon at 719-221-8329 or via email at Chad@Coloradotpa.org if you should wish to discuss these matters further.

Sincerely,

Scott Jones, Esq.

Authorized Representative – COHVCO

Executive Director CSA

Chad Hixon

Executive Director – TPA

[1] For a more detailed discussion of what should be a deeply concerning issue please see: Bees are ‘fish’ under Calif. Endangered Species Act – state court | Reuters

[2] See, Lugo; Insect Conservation under the Endangered Species Act; Journal of Environmental Law; Vol. 25:97 (2006) at pg. 97.

[3] See, Entomological Society of America; ESA Position Statement on Threatened and Endangered Insect Species: Protecting insects is vitally important to the United States. A full copy of this document is available here: ESA-Position-Statement-on-Threatened-and-Endangered-Insect-Species.pdf (entsoc.org)

[4] See, Young, J., Mitchell, C., & Redpath, S. (2020). Approaches to conflict management and brokering between groups. In W. Sutherland, P. Brotherton, Z. Davies, N. Ockendon, N. Pettorelli, & J. Vickery (Eds.), Conservation Research, Policy and Practice (Ecological Reviews, pp. 230-240). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108638210.014 at pgs. 231-233.(emphasis added)

[5] See, US Fish and Wildlife Service; Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status With Section 4(d) Rule for the Silverspot Butterfly; Federal Register; Vol. 87, No. 86; May 4, 2022 at pg.26330.

[6] See, Hammond, P.C. and D.V. McCorkle. 1983(84). The decline and extinction of Speyeria populations resulting from human environmental disturbances (Nymphalidae: Argynninae). Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 22:217-224.

[7] See, Nichols et al; Thresholds for conservation and management: structured decision making as a conceptual framework; Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; US Geological Service; 2014

[8] See, Freckleton, R. (2020). Conservation decisions in the face of uncertainty. In W. Sutherland, P. Brotherton, Z. Davies, N. Ockendon, N. Pettorelli, & J. Vickery (Eds.), Conservation Research, Policy and Practice (Ecological Reviews, pp. 183-195). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108638210.011 at pg. 183. A complete copy of chapter 11 of this review is included with these comments for your convenience as Exhibit “1”. (Hereinafter referred to as the “Sutherland Book” for purposes of these comments.

[9] See, Woods et al; Uncertainty and the Endangered Species Act: Indiana Law Journal volume 83:529 at pg. 531.

[10] See, Sutherland at pg. 185.

[11] Supra note 10.

[12] See, Pardo, S., Cooper, A. B., Reynolds, J. D., et al. 2018. Quantifying the known unknowns: estimating maximum intrinsic rate of population increase in the face of uncertainty. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 75, 953–963.

[13] See, Millspaugh et al: Models for planning wildlife conservation in Large Landscapes; Elsiver Press 2009 at pg. 51.

[14] See, Millspaugh et al; Note #10 at pg. 51.

[15] See, Carroll et al; Biological and Sociopolitical Sources of Uncertainty in Population Viability Analysis for Endangered Species Recovery Planning; Scientific Reports; July 12, 2019

[16] See, Wikipedia.com; definition of scientific modeling @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_modelling accessed September 1, 2020

[17] See, Zwilling, Martin: 7 Steps for Establishing the Right Business Model; January 30, 2015.

[18] See, https://www.wikihow.com/Make-a-Mathematical-Model

[19] See, Orloff & Strong; Models for planning wildlife conservation in large landscapes; 2009

[20] See, Millspaugh et al; Models for Planning Wildlife Conservation in Large Landscapes, Elsiver Publishing 2009 at pg. 5. Internal citations omitted

[21] See, US Fish and Wildlife Service; Proposed Rules; Endangered and Threatened Plants and Wildlife; Designation of critical habitat for the Mississippi Gopher Frog; Federal Register; Vol. 75, No. 106 pg. 31387; Thursday, June 3, 2010 at pg. 31404.

[22] A copy of this review is available here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/wildlife-habitat

[23]See, US Fish and Wildlife Service; Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status With Section 4(d) Rule for the Silverspot Butterfly; Federal Register; Vol. 87, No. 86; May 4, 2022 at pg. 26324

[24] See, Nora Braak, Rebecca Neve, Andrew K. Jones, Melanie Gibbs, Casper J. Breuker; The effects of insecticides on butterflies – A review; Environmental Pollution, Volume 242, Part A, 2018, Pages 507-518,

[25] See, Braak note 21 at pg. 515.

[26] See, Braak et al; note 22 at pg.

[27] See, SSA at pg. 29.

[28] See, Callippe silverspot butterfly – Wikipedia

[29] The Organizations are aware of limited highly theoretical research that indicates the issue needs more research. Given the inconclusive nature of the efforts it is not discussed here.

[30] See, SSA at pg. 12.

[31] See, SSA at pg. 12.

[32] See, SSA at pg. 18.

[33] For a detailed discussion of the uncertainty inherent in these processes please see: Schultz et al; Does movement behaviour predict population densities? A test with 25 butterfly species; Journal of Animal Ecology 2017, 86, 384–393

[34] See, US Fish and Wildlife Service; Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status With Section 4(d) Rule for the Silverspot Butterfly; Federal Register; Vol. 87, No. 86; May 4, 2022 at pg.26330

[35] See, Bees are ‘fish’ under Calif. Endangered Species Act – state court | Reuters