February 22, 2013

Public Comments Processing

Attn: FWS–R6–ES–2011–0111

Division of Policy and Directives Management

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

4401 N. Fairfax Drive, MS 2042–PDM

Arlington, VA 22203

RE: Gunnison Sage Grouse Critical Habitat

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the comments of the Organizations identified below regarding possible impacts from designation of critical habitat for the Gunnison Sage Grouse. The Organizations believe that the protection of any endangered or threatened species is a critical part of federal land management. The Organizations comments are directed at management standards in the critical habitat, rather than specific boundaries of the critical habitat. The Organizations are aware that critical habitat can be managed to benefit the species and maintain recreational usage and associated benefits for local communities for that habitat based on their active participation in user group discussions with CPW and FWS regarding management of Endangered and Threatened species in Colorado, such as the Lynx and Wolverine. These user group activities have allowed us to conclude that threatened or endangered species can be managed in conjunction with recreational activities on public lands in Colorado.

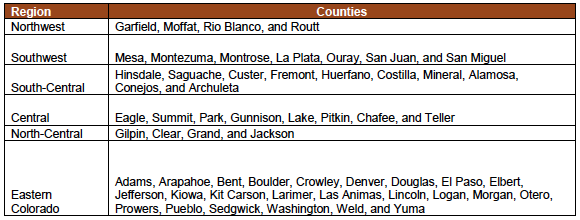

As specifically noted in the Gunnison Sage Grouse listing decision, recreational usage of habitat areas is a low level threat to the Grouse. While recreational usage is a low level threat, the economic benefits that are derived from recreational opportunities on federal lands are a critical component of the Colorado economy and many local communities that are within the areas to be designated as critical habitat. These economic impacts must be addressed in conjunction with the designation of any critical habitat.

Prior to addressing the specific concerns of the habitat designations, a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 2,500 members seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to insure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. For purposes of these comments, Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition and the Trail Preservation Alliance will be referred to as “the Organizations” in these comments.

There are significant economic contributions derived from the recreational use of public lands, and these contributions are directly related to the dispersed route network that is currently in place for summer usage on areas to be designated as habitat. The Organizations believe there are several types of seasonal route designations that would limit the minimal impacts on the Grouse from these recreational resources. These designations must be meaningfully addressed prior to closure of any route. The Organizations believe the first step that must be taken to protect recreation in habitat areas is addressing benefits of limiting travel to existing routes. Currently significant portions of the proposed critical habitat areas are managed as open areas for summer usage, meaning recreational usage is allowed throughout the area, rather than just existing routes. Restricting summer travel to existing routes in these areas would provide a significant benefit to the Grouse and the sage brush habitat the Grouse depends on.

If a designated route system is found to be insufficient, the Organizations believe that limited seasonal closures of routes and adjacent lek areas to all uses would be highly effective in minimizing impacts to Grouse actively using lek areas. As repeatedly noted in the listing decision, there are a wide range of factors negatively impacting the Grouse. Closures of lek areas only to motorized trail recreation will not benefit the grouse significantly, given the numerous threats to the Grouse and the minimal threat that recreation poses to the Grouse.

Recreational users of routes in areas currently managed under these standards will be familiar limited seasonal closures of routes for a wide range of reasons ranging from elk calving areas to heavy spring runoff. The currently high levels of awareness of these management standards will insure high levels of compliance with seasonal closures. The Organizations are aware that many of the routes in the vicinity of lek sites may already be subject to seasonal closures for other reasons.

The Organizations believe the application of seasonal wheeled closures to lek areas must also provide flexibility to allow certain routes of significant importance for accessing areas outside the habitat area to remain open with requirements of remaining on the route. Closing a route that provides the sole means of access to a parking area or other access points to lands that are beyond the critical habitat boundaries will also limit recreational usage of the non-habitat area. This will compound any economic impact concerns and generate little benefit to the Grouse or its sage brush habitat.

The Organizations are vigorously opposed to any large scale summer route closures of habitat areas beyond those necessary for the seasonal protection of lek areas and maintenance of habitat areas. The Organizations are very aware that closures of all routes on public lands will not off-set the impacts of development on private lands adjacent to the public lands. Support of private land owners will be a key component of any meaningful recovery of the Sage Grouse and large scale closures would not aid in building these relationships. The importance of these partnerships and public support is critical as critical habitat designation decision specifically states private lands in habitat areas range from 32-86.4% of the habitat area.1 Conservation easements and other protective designations developed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife management of Greater Sage Grouse and many other species inhabiting the areas subject to the conservation easement has only developed as a result of partnerships with private land owners.

The Organizations believe moving to a designated route system for summer travel, with limited seasonal closures for protection of leks in the proposed critical habitat areas would provide significant protection for the Grouse and the sage brush habitat the Grouse is dependent on, while appropriately balancing economic benefits that are provided to the Colorado economy from the dispersed trail network.

1. Additional comment periods should be provided to allow public comment on proposed critical habitat management standards and designations.

The Organizations appreciate the Agency’s request for submission of economic impact data as part of the habitat designation process and rulemaking, as this designation is a major federal action subject to Administrative rulemaking requirements and Endangered Species Act requirements. While this opportunity is welcomed, the Organizations are very concerned that a comment period would not be provided to allow for comment on how the economic impact information which is being provided in this round of comments is integrated into the management standards for habitat designation. Final development of these standards is often a critical component of habitat designation.

The Proposal seeks to obtain basic input regarding economic interests in the following manner:

“The economic analysis will estimate the economic impact of a potential designation of critical habitat on these activities. During the development of a final designation, we will consider economic impacts, public comments, and other new information, and areas may be excluded from the final critical habitat designation under section 4(b)(2) of the Act and our implementing regulations at 50 CFR 424.19.” 2

While this request for information is appreciated, an additional comment period would allow for meaningful public comment of final management standards in the habitat areas. These standards will directly impact usage of the habitat areas and a proper balance of protection of the Grouse and economic impacts will significantly further partnerships for future protection of the Grouse. The Organizations believe the current request is insufficient to satisfy the requirements of critical habitat designation, which require a final rule or position be provided to the public as part of the comment process. These regulations are clarified in the code of federal regulations as follows:

“§ 424.19 Final rules—impact analysis of critical habitat. The Secretary shall identify any significant activities that would either affect an area considered for designation as critical habitat or be likely to be affected by the designation, and shall, after proposing designation of such an area, consider the probable economic and other impacts of the designation upon proposed or ongoing activities. The Secretary may exclude any portion of such an area from the critical habitat if the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits of specifying the area as part of the critical habitat. The Secretary shall not exclude any such area if, based on the best scientific and commercial data available, he determines that the failure to designate that area as critical habitat will result in the extinction of the species concerned.”

It has been the Organizations experience that there are a wide range of options for integrating any information into the planning process and choosing the proper course and management balance for the information is a critical part of the rulemaking process. While the Organizations believe there are many ways to minimize economic impacts, such as seasonal closures of routes adjacent to lek areas and the protection of habitat that result from a designated trail system, the Organizations are not able to meaningfully comment on the sufficiency of any regulations on minimizing economic impacts. Providing an additional comment period would allow the public to address any concerns that might arise in the application of this economic impact information. Avoiding such a conflict will generate significant public support for the proposal and benefit the Grouse in the long run.

As the Organizations are unable to address any issues that might surround how the economic impact information obtained in response to the current open request is integrated into the final critical habitat designation, the Organizations vigorously assert that an additional comment period be provided to address any local issues or areas that impacted by the final designations.

2. Recreational usage of habitat areas is not a significant threat to Gunnison Sage Grouse.

The Organizations are very aware there are a large number of issues involved with the decline of all Grouse species, including urbanization of habitat, grazing, oil and gas exploration and increased predation. While there are a large number of threats to the grouse, recreational usage of habitat areas has been a concern that has been consistently identified as a lower level threat. The low level threat of recreation to the Grouse is clearly identified in the listing decision issued in conjunction with the proposed critical habitat designations, which specifically states:

“Recreational activities as discussed above do not singularly pose a threat to Gunnison sage-grouse. However, there may be certain situations where recreational activities are impacting local concentrations of Gunnison sage grouse, especially in areas where habitat is already fragmented such as in the six small populations and in certain areas within the Gunnison Basin.” 3

In the recently released listing decision for the Greater Sage Grouse, recreational activity was also identified as a low priority threat.4 Management of the impact of roads on Grouse in habitat areas is a key component in the habitat designation process as the listing decision notes that all grouse habitat is at least indirectly impacted by roads.5 The Organizations are keenly aware that wildlife response to a high volume, high speed arterial road is consistently higher than the response to a low speed, low volume forest service type road. Research indicates that Grouse display a hierarchical response to levels of road use.6 Road access to recreational areas is a key component of most users recreational experience on public lands and this access is frequently only provided by low speed, low volume forest service roads. Frequently many of these routes see very minimal levels of usage during the week, which should be taken into account in management of these routes.

While roads are also identified as a possible threat to the Gunnison sage grouse, the Organizations believe many of the factors addressed in the road section are not truly related to the usage and existence of the road in the habitat area. The Organizations believe many of the factors currently discussed as road impacts are more accurately summarized as urbanization of private lands, given the extensive discussions of residential development and population growth as part of the roads analysis. While these private land factors certainly impacting Grouse, these factors will not be addressed by management of public lands on areas adjacent to the areas being impacted by private land urbanization. Management of these private land factors is heavily dependent on public support for the Grouse planning process and programs such as CPW’s conservation easement programs.

Wide ranging route closures on public lands will not create support and partnerships necessary for protection of habitat areas that are on private lands. The Organizations must again vigorously stress closing routes on public lands is simply insufficient to offset impacts of high levels of development on adjacent private lands which can comprise too high a percentage of habitat areas for closures on public lands to be effective. Such closures would create minimal benefit to the grouse but would create very significant economic impacts to local and state level economies. As outlined in other portions of these comments the Organizations believe requiring a designated route system in habitat and if necessary adopting reasonably sized seasonal closures of routes around lek sites would be very effective tools for the protection of mating areas and minimize economic risks. Habitat management standards must allow flexibility for management of routes in habitat areas to properly and accurately address the higher levels of response to high volume high speed roads when compared to a 36 inch wide path that may only be used a few days a month.

3. Route closures will impact a wide range of uses resulting in greater negative economic impacts.

The Organizations are very concerned about any loss of routes and trails in areas that are to be designated critical habitat for the Grouse. The availability of these routes and trails for all recreational usage provides significant economic contributions to the many small municipalities in the vicinity of the habitat area. The high levels of recreational usage of these routes compounds risks of negative economic impacts from the loss of other economic activities on these lands. Economic impacts to non-recreational activities has already been identified as a significant concern, which was clearly articulated by the Western Governors Association in 2011 as follows:

“The economic impacts of placing sage-grouse on the endangered species list would be severe, since much of the West’s grazing of rangeland, natural gas, oil, coal and wind resources coincide with sage-grouse habitat.” 7

Significant restrictions on access would clearly impact activities for which concern has already been voiced by the Western Governors Association. In addition to the priority economic concerns identified by the Western Governors Association, the Organizations would add economic impacts from losses of recreational usage of public lands as an additional element to be addressed as a significant concern. The dispersed trail network in the habitat areas provides significant access for all users of the areas, not just those seeking a motorized experience.

4a. Trail based recreation is an economic mainstay for many local economies.

Many small communities in the vicinity of designated critical Grouse habitat are heavily dependent on recreational activities and tourism for survival of the community, after more traditional income sources like the mining and timber industries have left these areas. US Forest Service research indicates that a multiple usage trail network is an effective tool for the development and maintenance of local economies. This research specifically concluded:

“Recreation and tourism economies are the mainstay for rural counties with high percentages of public land. Actions by public agencies to reduce or limit access to for recreation have a direct impact on local pocket books. Limiting access by closing roads, campgrounds, RV parking, and trails for all or one special interests group will impact surrounding communities. Visitors to public lands utilize nearby communities for food, lodging and support facilities.” 8

While the development of a recreational trail network can be a significant benefit to local communities, the converse of this is also true as the loss of an existing recreational trail network can create significant negative economic impacts. The scope of losses from large route closures has been the basis for several studies. The findings of this research are consistent with the concerns regarding closures of routes voiced in these comments. In 1999 a joint study of University of Wyoming and US Department of Agriculture found that 72% of economic benefits from winter recreation would be lost with a seasonal closure of the Yellowstone Park to motorized recreation.9 The high levels of economic impact to communities from closures is the result of the wide range of user groups that use a trail network to obtain their primary recreational experience. The Organizations vigorously believe large scale closures in Grouse habitat areas would have a similar impact on the local communities as those experienced by the communities adjacent to Yellowstone Park. These must be avoided.

4b. Dispersed trails are multiple use resources.

The Organizations believe that a brief discussion of what an OHV recreational user is will clarify why multiple use trails are of such concern when addressing economic impacts. Forest Service research indicates that families are the largest group of OHV users. This research found that almost 50% of users were over 30 years of age and highly educated. 11.4% of OHV users are 51 years of age or older.10 Women were a large portion of those participating in OHV recreational activities.11 This research indicates that OHV recreationalists are frequently a broad spectrum outdoor enthusiasts, meaning they may be using their OHV for recreation one weekend but the next weekend they will be walking for pleasure (88.9%), using a developing camping facility (44.7%), using a Wilderness or primitive area (58.1%) fishing (44.6%) or hunting (28.4). 12

As noted by the Forest Service research, motorized access to public lands is a key component of any recreational activity. This is completely consistent with the Organizations experiences for all recreational activities as most users to not have access to non-motorized means of game retrieval or do not have sufficient time to hike long distances to gain access to their favorite fishing hole or dispersed camping site. The wide range of recreation utilizing the dispersed trail network again weighs heavily in favor of caution of maintaining recreational access to areas that are to be designated Grouse habitat.

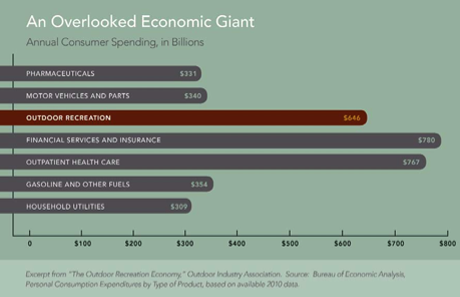

5a. Recently released research from the Western Governors Association finds recreational activity on public lands is largest economic contributor to western states.

In 2012, the Western Governors Association released the conclusions of multiple year research regarding the economic impacts of recreation to western states economies. A complete copy of this report has been included with these comments for your reference. Given the scale of these findings, the Organizations believe recreational usage would now be added to the priority concerns identified previous by the Western Governors Association. Recreation is the largest economic contributor to western state economies from public lands, which position is summarized in the report as follows:

“The Get Out West Advisory Group identified successfully managing the West’s recreation assets as a key factor in facilitating positive outdoor recreation experiences for the region’s citizens and tourists and for local economic development and job creation in communities around these places.” 13

This research also compared recreational contributions to many other economic activities that were present in western states. These conclusions were summarized as follows:

14

The Western Governors economic impact analysis also highlighted 35 recreational opportunities throughout the western states. The overwhelming majority of these highlighted recreational locations involved the use of a dispersed trail network as part of the recreational experience. While many of these opportunities are outside areas to be designated habitat, analysis of these highlighted locations clearly evidences the critical role that the dispersed trail network plays in all recreational activities.

This research did identify other activities as larger economic contributors to western states, but these activities were not connected to public lands or small municipalities such as those impacted by the critical habitat designation. Western Colorado communities are simply not know as banking, health care or insurance centers of the western states. They are however known for their exceptional recreational opportunities. The Organizations believe these findings warrant clear management standards that properly balance economic impacts from closures with benefits to the Grouse from the management standards. Failure to properly measure and balance all recreational interests will have profound effects on recreational access to public lands and will result in significant negative economic impacts to all communities that will do little to benefit the Sage Grouse.

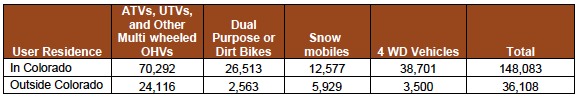

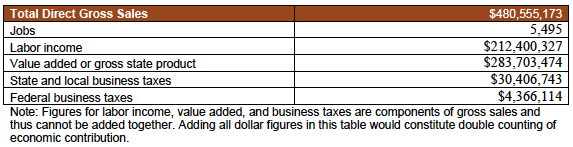

5b. Dispersed motorized recreation contributes over $1 billion a year to the Colorado economy.

Recreational usage of public lands is a significant portion of the Colorado economy, especially in the smaller mountain communities which have already lost more traditional sources of revenue, such as timber, farming and mining. In 2008, COHVCO commissioned an economic impact study to determine the economic impacts of OHV recreation on the Colorado economy.15 A copy of this economic impact study is attached for your reference. This study found that over 1,000,000,000 dollars of positive economic impact and 10,000 jobs resulted from OHV recreation to the State economy. Over $400,000,000 of this economic impact and almost 5,777 jobs were result from motorized recreation in the county areas proposed to be designated as critical habitat are located. 16

In addition to this direct positive economic impact to Colorado communities, OHV recreation accounted for over $100,000 million in tax revenue to state and local municipalities.17 These are tax revenues that motorized recreational users of the forest pay with little objection to obtain the benefits of their sport, and are used to address a wide range of needs for the local municipal government. Given current economic conditions, our Organizations believe these positive economic impact numbers must be meaningfully addressed in all government activities.

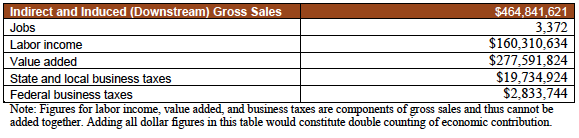

5c. Colorado Parks and Wildlife identifies the significant positive impacts to the Colorado economy from hunting and fishing in Grouse habitat areas.

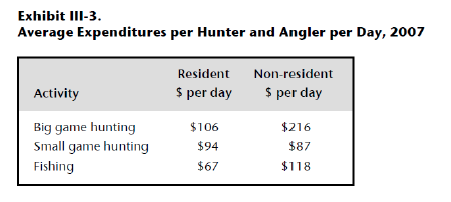

In 2008, Colorado Parks and Wildlife commissioned a study to determine the economic impacts to the Colorado economy from hunting and fishing. A discussion of these impacts is provided as a part of these comments in order to allow for full understanding and analysis of the significant impacts that are associated with the dispersed trail network in the areas to be designated as critical habitat. Closures of dispersed trail networks are frequently of significant concern to those who use the dispersed trail networks for hunting and fishing activities. These impacts are not provided to open discussions regarding hunting of the Grouse, as the listing decision notes hunting of Grouse is Colorado has been properly prohibited for a significant period of time.

The CPW report identified that hunting and fishing provided over $1.8 billion to the Colorado economy in 2008. 18 For many hunters and fisherman, motorized access on the dispersed trail network is a key component of their hunting and fishing experience as the average hunter does not have access to teams of horses to remove elk from inaccessible areas or days to hike into their local fishing area. These access related expenditures are encompassed in the CPW economic impact calculation as analysis includes expenditures for trucks, campers, recreational vehicles, boats and other motorized equipment.19 Access related expenditures that can only be fully utilized for hunting and fishing with the existence of a dispersed trail network.

The CPW analysis also identified spending on hunting and fishing in the Colorado counties that are impacted by designations of critical habitat as follows:

20

The Organizations believe that economic impacts from possible reductions in hunting and fishing activity in areas to be designated as critical habitat must also be accounted for in the development of management standards for the critical habitat. As clearly identified by CPW, these economic contributions are significant and access is a key component of the hunting and fishing experience for most users.

6. The status proposal finds OHV users are a highly law abiding user group on public lands, which conclusions are supported by recent CPW research.

The significant economic contributions provided to the Colorado economy from the dispersed trail network in proposed habitat areas warrants a serious review of all possible management strategies to address impacts to habitat areas before closures are adopted. As noted elsewhere in these comments, these steps would include moving to a limitation of use of existing routes in the habitat areas and reasonable sized seasonal closures. The use of seasonal closures has been specifically identified as an effective tool for management of the dispersed trail network which results in significant protection of active leks.

The Organizations are aware the effectiveness of these changes would be heavily dependent on compliance with the restrictions by users. Research indicates that users are highly compliant with seasonal closures and restrictions to existing routes. The high level of compliance was directly addressed in the status decision as follows:

“The BLM and Gunnison County have 38 closure points to minimize impacts to Gunnison sage-grouse within the Basin from March 15 to May 15 each year (BLM 2009, p. 40). While road closures may be violated in a small number of situations, road closures are having a beneficial effect on Gunnison sage-grouse through avoidance or minimization of impacts during the breeding season.” 21

The Organizations are aware that limitations to existing routes and seasonal closures have been highly effective tools for addressing wildlife issues in other areas due to the high levels of user compliance with these type of restrictions. These high levels of compliance are only briefly addressed in the status proposal but more extensively discussed in the findings of the law enforcement pilot program developed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife to address alleged law enforcement concerns with OHV recreation. This Pilot was developed in partnership with the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management and is providing some of the first concrete information regarding compliance with use restrictions by those involved in OHV recreation.

The OHV law enforcement pilot program was created to address on-going assertions of a compelling need to stop resource damage caused by OHV misuse at locations identified as violation “hotspots” by those seeking to limit public access to public lands. As part of the pilot program there were several targeted enforcement days in areas now proposed to be designated as grouse habitat, making the pilot program findings highly relevant for user compliance concerns in Grouse habitat areas. The law enforcement pilot program deployed additional trained professional law enforcement officers, funded by funds from the OHV registration funds, to these “hotspots” during heavy usage times to supplement existing law enforcement resources in these areas. As part of the pilot, the additional officers we required to keep logs of their contacts for reporting purposes.

The findings of this pilot clearly identify that these “hotspots” for OHV violations were anything but “hotspots”. Over last two summers, officers involved in the pilot program contacted over 23,000 people of the 160,000 registered OHVs in Colorado, creating an astoundingly large sampling. This pilot program found that less than 5% of riders committed any violations. The overwhelming percentage of these violations were people not registering their OHV. Only 1.8% of contacts involved activities, other than failing to register OHVs, where the officer found the activity serious enough to issue a written warning or issue of a citation for a resource impacting violation.

The Organizations believe the conclusions of this groundbreaking research are highly relevant to this discussion. These findings will provide a high degree of reassurance to those with concerns about possible limited compliance with restrictions limiting improvements to Grouse populations and sage brush habitat. These findings weigh heavily in favor of mitigating economic risks by only permitting use of existing trails and seasonal closures to protect active lek areas.

7a. Decisions regarding the lack of impact of motorized recreation on the Greater Sage Grouse must be accounted for in habitat management.

As noted in the status proposal for the Gunnison Sage Grouse, the Greater Sage Grouse research remains relevant to the management of the Gunnison Sage Grouse. The status decision clearly states:

“Gunnison sage-grouse and greater sage-grouse (a similar, closely related species) have similar life histories and habitat requirements (Young 1994, p. 44). In this proposed rule, we use information specific to the Gunnison sage-grouse where available but still apply scientific management principles for greater sage-grouse (C.urophasianus) that are relevant to Gunnison sage-grouse management needs and strategies….” 22

As previously noted in these comments, listing decisions relative to both the Greater and Gunnison Sage Grouse have explicitly found that recreational usage of Sage Grouse habitat is a low priority threat to the habitat. While the FWS findings cited above do not specifically identify dispersed motorized recreation, they provide an extensive discussion of possible motorized recreational impacts prior to concluding that recreation has a minimal impact on the sage grouse. The 2010 USFWS listing decision again stated that adoption of a designated trail system for recreational purposes is of significant benefit to the sage grouse. The 2010 USFWS listing decision discussed changes to designated trails on USFS lands as follows:

“As part of the USFS Travel Management planning effort, both the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest and the Inyo National Forest are revising road designations in their jurisdictions. The Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest released its Draft Environmental Impact Statement in July, 2009. The Inyo National Forest completed and released its Final Environmental Impact Statement and Record of Decision in August 2009 for Motorized Travel Management. The ROD calls for the permanent prohibition on cross country travel off designated authorized roads.” 23

Clearly, if the designated route system that was being adopted by these Forests was insufficient for the protection of Sage Grouse habitat, such a position would have been clearly stated in this discussion given the large body of research that exists for the management of the Sage Grouse.

7b. Two recently released texts support FWS positions regarding the minimal risk recreational usage of habitat areas poses.

Two recently released texts from nationally acknowledged grouse experts have specifically addressed the management of Greater Sage Grouse habitat and included extensive discussions of all possible threats to Grouse.24 The Organizations believe it is significant to note that the Sandercock text simply never addresses possible motorized recreational concerns in habitat areas. The Knick and Connolly text discusses OHV recreation in a very general manner in two paragraphs of a text that totals 646 pages.25 This discussion only addresses trends in usage of OHVs. These limited analysis is significant as these are resources one would expect to include significant discussions of OHV recreational impacts on the Grouse if these were significant concerns regarding OHV recreation creating possible impacts on the Grouse.

While these texts do not significantly address motorized recreation, the texts do specifically confirm access to public lands is a major issue for grouse management. The Connolly text specifically states:

“Many people live in these locations primarily because of access to public lands for recreation.” 26

The Organizations must note the texts identification that living in an area primarily for access to public lands supports the Organizations concerns regarding the type of impacts that must be balanced in the creation of management standards for critical habitat areas.

The Organizations are aware there is a significant body of peer reviewed research for the management of the Grouse. The Organizations believe any concerns regarding dispersed recreation on the Grouse would have been identified in the current body of research summarized in these texts. The Organizations believe the minimal discussion of this issue clearly supports the position that was taken in the 2010 Greater Sage Grouse listing decision, mainly that dispersed recreation is a minimal threat to the Grouse. As the benefits of a designated or existing trail system are approved in the listing decision and the minimal threat of impacts from motorized recreation is simply not discussed in two recent texts from National experts on the Grouse, the Organizations believe restricting travel to existing routes in Grouse habitat is a logical, scientifically based and credible starting point for addressing motorized access to critical habitat areas.

8a. Restricting travel to existing routes would provide significant benefit for the Grouse with minimal economic risk in critical habitat areas.

The Organizations are intimately familiar with designations of routes under the Forest Service’s Travel Management rule. The Organizations would support limitations of travel to existing routes in critical habitat areas of the Grouse as part of a critical habitat designation. As previously noted in the Greater Sage Grouse listing decision, a designated route system appears to be a significant benefit to maintaining sage grouse habitat and sage brush health. The Organizations believe these designations would be highly complied with if properly implemented, as most users are very familiar with requirements to stay on designated routes for travel as this is the common standard for dispersed route travel on public lands.

While the designation of travel routes is basically completed for Forest Service lands in the areas proposed to be designated Critical habitat for the Grouse, the designation process remains on going for many areas that are under BLM management. This has resulted in large portions of the critical habitat not being currently subject to a requirement that travel is limited to existing routes. The Organizations believe that restricting all travel to existing routes in habitat areas would provide significant benefit to the Grouse and the sage brush the grouse depends on for habitat, when compared to the current open area designations. The Organizations believe such a change could provide significant benefit to the Grouse with very little risk of negative economic impacts to local communities as recreational access and opportunities could be maintained. The Organizations believe the significant benefits that can be achieved for the Grouse at minimal costs weighs heavily in favor of meaningful analysis of limiting travel to existing routes as a method to preserve public access to the habitat areas.

8b. Use of seasonal route closures to avoid lek areas would minimize economic impacts.

As part of the travel management process, seasonal limitations on use of designated routes are frequently made to avoid wildlife habitat areas or to avoid sensitive areas at a particular times of the year for a particular species, such as spring closures of routes in elk calving areas. These seasonal closures have been found to be highly effective in limiting impacts on wildlife during these sensitive periods and maintaining public access to these areas for the rest of the year when the species has moved from the area. In the case of elk calving areas, elk simply do not use calving areas in the summer as the elk traditionally move to higher areas for grazing purposes. As the elk have moved from these areas, use of routes in the area creates little to no risk of negative impacts to the animals.

Similar to elk, research indicates that sage grouse habitat and needs varies greatly over the course of a year.27 The habitat designation decision notes this highly seasonal mobility as follows:

“Gunnison sage-grouse make relatively large movements on an annual basis. Maximum Gunnison sage-grouse annual movements in relation to lek capture have been reported as 18.5 km (11.5 mi) (GSRSC 2005, p. J–3), and 17.3 km (10.7 mi) (Saher 2011, pers. comm.), and individual Gunnison sage-grouse location points can be up to 27.9 km (17.3 mi) apart within a given year (Root 2002, pp. 14–15). Individual Gunnison sage-grouse have been documented to move more than 56.3 km (35 mi) to wintering areas in the Gunnison Basin in Colorado (Phillips 2011, pers. comm.). While it is likely that some areas encompassed within these movement boundaries are used only briefly as movement areas, the extent of these movements demonstrate the large scale annual habitat requirements of the species.” 28

Given the high levels of mobility displayed by the Grouse throughout the year, closing routes in all habitat areas would be problematic from an economic perspective. The overwhelming body of grouse research surrounds impacts and activities of the grouse in their lek areas, where population concentrations are highest and where the highest response to disturbance is identified. Research also indicates that lek areas are annually used for long periods of time by the same group of Grouse.29 Discovery of new lek locations is a rather rare occurance and discovery of single new lek sites was of enough significance to warrant noting in the status decision.30 As researchers appear to have identified almost all lek areas in the critical habitat areas, this will make identification of routes around active leks in the critical habitat areas a management tool that could be quickly used to gain significant benefits to the Grouse.

Research indicates that seasonal closures for the protection of leks is a highly effective tool, which the status decision specifically notes as follows:

“The BLM and Gunnison County have 38 closure points to minimize impacts to Gunnison sage-grouse within the Basin from March 15 to May 15 each year (BLM 2009, p. 40). While road closures may be violated in a small number of situations, road closures are having a beneficial effect on Gunnison sage-grouse through avoidance or minimization of impacts during the breeding season.” 31

The Organizations believe that seasonal closures of routes will also only be effective if the nesting areas are seasonally closed to other uses as well. Clearly closing a route to address concerns regarding its proximity to leks and nesting areas will not be effective if grazing, lek viewing and other activities identified as similar or higher risk activities for the habitat areas are continued.

9. Recreational closures alone are insufficient to address habitat concerns.

As extensively noted in both the status and habitat proposals, there are a wide range of activities that are negatively impacting the Gunnison Sage Grouse, many of which are higher priority threats than recreational usage of the habitat areas. The following provisions are included in these comments to highlight some areas and activities that must also be addressed if large scale route prohibits are found to be required. It has been the Organizations experience with other endangered or threatened species that often isolation of a single usage to address impacts from a wide range of usages creates significant public opposition as users being restricted believe they are being singled out arbitrarily. Management decisions isolating single uses frequently fail and generate significant public opposition for future management of the issue.

The need to address a wide range of issues is supported in the status decision as closures of recreational access alone is insufficient to address habitat degradation, as the status decision specifically notes as follows:

“Based on modeling results demonstrating the effects of roads on Gunnison sage-grouse (Aldridge et al. 2011, entire—discussed in detail in Factor A), implementation of even the most restrictive travel management alternatives proposed by the BLM and USFS will still result in further degradation and fragmentation of Gunnison sage-grouse habitat in the Gunnison Basin.” 32

The Organizations vigorously believe that if access to any area is to be closed for recreational purposes, other higher priority threats must also be prohibited in that area, as research indicates recreational closures simply will never be sufficient to address the wide range of activities that degrade habitat areas. The Organizations are vigorously opposed to any decisions to rely on a single activity to address the wide range of habitat issues, in light of the research that indicates prohibitions of that activity will simply never address the habitat issues contributing to the Grouse’s decline.

Several of the wide range of factors identified as habitat concerns are noted here as these issues would also have to be addressed with closures to address the decline of the Sage Grouse, many of which are not related to recreational activities. Dogs are a factor that significantly impairs habitat quality as noted in the status decision:

“Domestic dogs accompanying recreationists or associated with residences can disturb, harass, displace, or kill Gunnison sage-grouse. Authors of many wildlife disturbance studies concluded that dogs with people, dogs on leash, or loose dogs provoked the most pronounced disturbance reactions from their study animals (Sime 1999 and references within). The primary consequences of dogs being off leash is harassment, which can lead to physiological stress as well as the separation of adult and young birds, or flushing incubating birds from their nest.” 33

The Organizations would be very opposed to any management standards for habitat areas that precluded motorized travel but continued to allow access for pedestrians with dogs as the listing decision specifically identifies similar levels of concern for these uses.

Grazing is also another usage of habitat areas that poses a similar level of threat to the habitat as roads. This concern is summarized in the listing decision as follows:

“Livestock management and domestic grazing have the potential to degrade Gunnison sage-grouse habitat. Grazing can adversely impact nesting and broodrearing habitat by decreasing vegetation available for concealment from predators. Grazing also has been shown to compact soils, decrease herbaceous abundance, increase erosion, and increase the probability of invasion of exotic plant species (GSRSC 2005, p. 173).” 34

The Organizations must also note that lek viewing is currently not a significant issue for the Sage Grouse, however the Organizations believe that access to the lek area for viewing would create similar if not higher levels of disturbance to the Grouse when compared to a person simply passing through the area. The Organizations believe that if all recreational trail access is fully closed in an area then these activities should be prohibited as well.

The Organizations must again note that the above activities are not singled out due to heightened concerns for the activities but rather to briefly identify many of the usages that would need to be prohibited in a habitat area if the decision was made to permanently close the area to trail usage. While these additional restrictions would create economic concerns, the Organizations believe these economic impacts would be balanced by the fundamental fairness of treating similar threats to the Grouse in a similar manner. It has been the Organizations experience that arbitrarily permitting some uses while prohibiting others often fosters significant frustration from the public and develops little public support for conservation efforts. Given the high levels of habitat areas that are in private lands, the Organizations believe public support will play a critical role in any long term recovery efforts for the Grouse.

10. Conclusion

The Organizations believe that the protection of any endangered or threatened species is a critical part of federal land management. Proper identification of the threats and issues causing any species to be endangered is critical to developing plans that do not significantly adversely impact local communities for the protection of that species. There is simply no argument to be made that the dispersed trail network in the habitat areas is anything other than a significant economic contributor to local and state economies. The research on this issue is irrefutable.

The Organizations believe the significant economic impacts warrant serious analysis of every step possible to protect the trail network and meaningfully improve habitat areas for the long term benefit of the Grouse. The Organizations believe research concludes that moving to a designated trail system in habitat areas would provide significant protection for the Gunnison Sage Grouse. The Organizations believe that limited size seasonal closures of routes adjacent to active lek areas would also provide significant benefits for the Grouse and protect the economic contributions to local communities from the dispersed trail networks. Both of these management standards have been shown to be effective at protecting and improving Grouse habitat.

The Organizations would be vigorously opposed to any attempts to close routes prior to utilization of designated routes and seasonal closures in a habitat area. If closures of routes was found to be necessary, research concludes there are numerous other uses in habitat areas that pose similar or higher threats to the grouse than the dispersed trail network. The Organizations believe all uses that pose threats to the Grouse must be prohibited if the dispersed trail network is closed. Arbitrarily selected permitted and prohibited uses often does little to foster public support for the habitat management actions and given the high levels of private lands in habitat areas, the Organizations believe public support will be a critical component of habitat management moving forward.

Please feel free to contact Scott Jones at 518-281-5810 or by mail at 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont, Co 80504 for copies of any documentation that is relied on in these comments or if you should wish to discuss any of the concerns raised in these comments further.

Sincerely,

John Bonngiovanni

Chairman and President

Colorado OHV Coalition

Don.E. Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

Scott Jones, Esq.

COHVCO CO-Chairman

1Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Gunnison Sage-Grouse; 78 Fed. Reg 2540 ( Jan. 11, 2013) at pgs 2552-2556. (hereinafter referred to as the “Habitat proposal”).

2Habitat Proposal at pg 2558.

3Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for Gunnison Sage-Grouse; 78 Fed. Reg. 2486 (Jan. 11, 2013) at pg 2533. (hereinafter referred to as the “status proposal”)

4 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Findings for Petitions to List the Greater Sage- Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) as Threatened or Endangered, Fed. Reg. (March 5, 2010) at Pg 75.

5Status proposal at pg 2499.

6Aldridge et al; Crucial Nesting Habitat for Gunnison Sage Grouse; A Spatially Explicit Hierarchical Approach; Journal of Wildlife Management; Vol. 76(2); February 2012; 391-406 at pg 404.

7Western Governors Association; Policy Resolution 11-9; Sage-grouse and Sagebrush Conservation; July 11, 2011 at pg 2.

8Humston et al; USFS Office of Rural Development; Jobs, Economic Development and Sustainable Communities Strategizing Policy Needs and Program Delivery for Rural California; February 2010 at pgs 51-52

9David Taylor; Economic Importance of the Winter Season to Park County Wyoming; University of Wyoming Press; 1999 @ pg 2.

10Cordell et al; USFS Research Station; Off-Highway Vehicle Recreation in the United States and its Regions and States: A National Report from the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment (NSRE) February, 2008; pg 56.

11Id at pg 56.

12 Id at pg 41-43.

13Western Governors Association; Managing the Regions Recreational Assets; Report of the Get Out West Advisory Group to the Western Governors’ Association; June 2012 – pg 1.

14Western Governors Association; A Snapshot of the Economic Impact of Outdoor Recreation; prepared by Outdoor Industry Foundation; June 2012 at pg 1.

15COHVCO Economic Impact Study- 2008; Lewis Burger Group; pg ES-5.

16Id at ES-6.

17Id at pg ES-5.

18Colorado Division of Wildlife; Final Report; The Economic Impacts of Hunting, Fishing and Wildlife Watching in Colorado; Sept 26, 2008; at pg Exec Summary at pg 1.

19Id at Section 3 pg 10.

20Colorado Division of Wildlife; Final Report; The Economic Impacts of Hunting, Fishing and Wildlife Watching in Colorado; Sept 26, 2008; at pg Exec Summary at section 4 pg 16 & 17.

21Status Proposal at pg 2532.

22Status proposal at pg 2488

2312-month findings for petition to list the Greater Sage Grouse(Centrocercus urophasianus) as threatened or endangered. Fed Reg. (March 5, 2010) at pg 92.

24Sandercock et al; Ecology, Conservation and Management of the Grouse; University of California Press 2011; see also ST Knick and JW Connolly (editors) Greater Sage Grouse; Ecology and conservation of a landscape species and its habitats. Studies in Avian Biology (vol 38), Univ of California Press, Berkeley CA.

25See, Knick and Connolly at pg 216.

26See, Knick and Connolly at pg 216.

27Connolly JW, ET Rinkes and CE Braun. 2011. Characteristics of Greater Sage Grouse habitats; a landscape species at micro- and macroscales. pg 69-83 in ST Knick and JW Connolly (editors) Greater Sage Grouse; Ecology and conservation of a landscape species and its habitats. Studies in Avian Biology (vol 38), Univ of California Press, Berkeley CA.

28Status proposal at pg 2543.

29Status proposal at pg 2488-2495.

30Status proposal at pg 2494.

31Status proposal at pg 2532 .

32Status proposal at pg 2526.

33Status proposal at pg 2532.

34Status proposal at pg 2505.

Full letter Full letter

Area Map Area Map

|